The first thing John Blackbird learned when he was growing up on the Canadian prairies was that his people were no good. Indians were history’s losers: dethroned, displaced, rounded up and ghettoized on the reserves. Raised by a white family from the age of nine, Blackbird heard from friends and classmates that natives were unreliable, lazy and unemployable. Even in childhood games, nobody wanted to be the Indian. They all wanted to play the gallant cowboy or the stalwart RCMP officer. But, like it or not, he was an Indian. He was taunted by the meaner white kids at school—and Blackbird responded the only way he could: with his fists.

Today, in Germany, John Blackbird is a star, a celebrity even. He’s seen as a descendant of the wild and free people of the plains, an embodiment of environmental respect and cooperation, a defender of the land the white man has despoiled. The 37-year-old Cree filmmaker and writer is routinely trailed on the streets by fans; he even signs autographs. He tours the country’s military installations, universities and elementary schools and is an honoured guest in people’s homes. He is consulted for his opinion on everything from the environment, to politics, spirituality and Native studies; he frequently holds workshops on these subjects. From the moment he got off the plane in Frankfurt in the mid-1990s, he was celebrated, feted and spoiled.

“They were so excited to [meet] me because Indians were admired in their storybooks,” says Blackbird. “I was amazed. When I was a kid, Indians definitely weren’t seen as heroes.”

Born in Saskatchewan and educated in Alberta, Blackbird was introduced to the German propensity for Indian hero-worship after meeting and marrying a German citizen in Meadow Lake, Sask., where he worked at the local television station. They had a child, and at his wife’s urging they relocated to Oldenburg in northwestern Germany. Within a few weeks, Blackbird was confronted with what is called the “hobbyist” movement. Its 40,000 members grew up fascinated with Native North American culture, thanks in no small part to the bestselling German author of all time, Karl May. May wrote four books and many short stories about an Apache warrior named Winnetou and his sidekick and German blood-brother, Old Shatterhand. First penned in 1892, the books’ characters roam the North American plains, using their nearly superhuman powers to fight off the land-hungry government and thuggish, violent pioneers. Fans of the stories included Adolf Hitler and Albert Einstein.

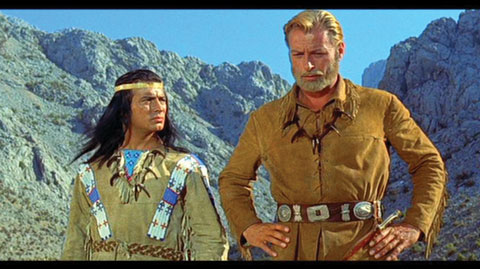

May was imprisoned for fraud several times and wrote under many pen names, including his wife’s. Contrary to his public declarations, he never visited North America. He made factual mistakes throughout his fiction; for example, he assumed the US southwest resembled the Sahara desert and described the Apache as living in pueblos and travelling in birch canoes in what is now Texas. But Winnetou was a great success and the author attracted worshipful crowds wherever he went. His books even made their way into communist countries, where they were handed from person to person in secrecy. In the 1960s, Winnetou and Old Shatterhand were immortalized in five films starring the French actor Pierre Brice and the American Lex Barker. Soon hobbyist (or “woodcraft” movements as they were called in communist countries), began forming across Europe. There are now over 400 hobbyist clubs in Germany alone.

Harald Reinl’s 1962 film Der Schatz im Silbersee (The Treasure of Silver lake).

Hobbyists take their proclivities very seriously. They spend their weekends trying to live exactly as Indians of the plains did over two centuries ago. They recreate teepee encampments in forests, public parks or on private farms, dress in animal skins and furs as “true” Sioux or Lakota did before the advent of modernity, and forgo modern tools, using moss, sticks and stone to make fire and handmade bone knives to cut and prepare food. They address each other by adopted Indian-sounding names such as “White Wolf.” Their materials, including blankets, drums and rattles, smudge and tomahawks, can be purchased from websites such as that of Indianershop Seven Arrows, based in Offstein. Some meticulously craft their own objects, using only the materials and technologies of the 17th and 18th centuries. Many feel an intense spiritual link to native myths and spirituality. They talk about “feeling” native on the inside.

“The hobbyists’ hearts are in the right place,” says Blackbird. “But it is strange to see so many white people taking photographs of themselves dressed in powwow regalia, facing each other like two warriors and looking as mean as they can. If I didn’t grow up with Mr. Dressup, I might have issues with it.”

Some aboriginals do take issue. When David Redbird Baker first went to Germany over a decade ago and saw adult Germans playing “Cowboys and Indians,” he thought it was cute. But he was offended when the hobbyists began staging sacred ceremonies like ghost and sun dances, naming ceremonies and sweat lodges. Baker lives in Mönchengladbach between Düsseldorf and the Dutch border, with his German wife and their son. An Ojibwa, Baker used to dance at German powwows and sell native crafts and beadwork through his website. When I spoke to him, he was in the process of closing up shop.

“They take the social and religious ceremonies and change them beyond recognition,” says Baker. “I feel bad because I used to encourage sharing. It would have been better to have kept my mouth shut.”

He says hobbyists have begun to develop a sense of ownership over aboriginal culture and claim the right to improvise on the most sacred rituals. They’ve held pipe and naming ceremonies, held dances where anyone in modern dress is barred from attending—even visiting aboriginals. They buy sacred items like eagle feathers on the Internet (even though some eagle species are endangered) and add them to their regalia. They’ve allowed women to dance during their “moon time,” which is, according to Baker, the equivalent of a cardinal sin. He compares it to an Indian walking into a Catholic church dressed in a priest’s vestments on a Sunday, drinking holy water out of a coffee cup and making a sandwich out of the host.

Baker says the most common story he hears from hobbyists is that they’re the illegitimate children of a missing or mysterious Native American soldier. Only one hobbyist he ever met was able to prove some link to native ancestry, and it turned out he was actually half-Mexican. “He was wandering around calling himself an Apache, a descendant of Geronimo,” he says.

Despite his frustration, Baker says he stays in Europe for his family’s sake. He suffered a stroke in 2003 and the family enjoys European medical and social benefits. But he insists he is never going to dance in Germany again.

“I’ll go back home to dance,” Baker says. “I won’t get myself involved with these people anymore. Everything encourages them. In Germany they’ll believe anything they see on paper and not believe the truth when it’s standing there talking to them. But if it were written in a book, it would be great. I’ve thought about getting some friends to make me up as a dancer in lederhosen, a short hat with a feather, wooden shoes and coming out during one of their grand entries slapping my hands. Maybe I should.”

Hobbyists take their proclivities very seriously. They spend their weekends trying to live exactly as Indians of the plains did over two centuries ago. They address each other by adopted Indian-sounding names such as “White Wolf.”

Over 420,000 German tourists visit Canada each year. The Alberta government, in their international marketing strategy, notes German tourists are a “priority” market—and actively cultivates their interest in aboriginal culture. For many Germans, the Calgary Stampede, Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump and Blackfoot Crossing are “must-sees.” Hobbyists go even further, hiring local aboriginals to take them on hunting trips or renting land to set up their teepees so they can sleep under an authentic prairie sky.

But there is traffic in both directions, and always has been, even dating back a few hundred years. Toward the end of the 19th century, many famous chiefs escaped poor living conditions by going to Europe, usually as part of a variety show dedicated to the glorification of the US frontier. When the Apache warrior Geronimo was in his dotage (and technically a prisoner of war), he travelled to Europe with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show in the late 1890s with other famous warriors: Sitting Bull of the Lakota, Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce, Sioux Chief Rains-in-the-Face, and Black Elk, an Oglala Sioux. They were extremely popular. Some stayed in Europe after the tour was over.

According to Carmen Kwasny of the Native American Association of Germany, in a country of some 82 million people, North American aboriginals number no more than a few hundred. Unless they apply for citizenship, their comings and goings are likely to remain invisible. Established in the 1980s by a couple of native soldiers in Heidelberg, the NAAOG began as a kind of a social club. They sponsored a few mini-powwows with other native dancers serving in the US armed forces. When they were shipped back home, a Hopi Native-American kept up the organization. He was a singer who had a small drum group and would use non-native dancers, mainly German women, to help raise money for the group. When he left, the NAAOG’s remaining members were all Germans.

As the new chairwoman, Kwasny still stages powwows, but she insists she is not like the hobbyists. “Some of them are really good people,” she says. “They put hard work into it. It’s amazing how much time they spend doing these arts. They can set up teepees in a really short time, skin an animal or make an arrowhead out of stone. But the problems come up when they try to be what they can’t be. They say, ‘My heart is like [a] Native American heart. I feel like a Native American,’ and then they think they would like to have their spiritual feelings. So many are looking for something they will probably never find.

John Blackbird (l) with Murray Small Legs, a Blackfoot storyteller and dancer from Alberta, in Berlin, 2007. (Photo Courtesy of John Blackbird)

“They mainly get their knowledge out of books,” she continues. “But then they mix it up, and [their] little group develops something new that doesn’t really exist, that never did, but they think it was like that. They say, ‘We want to be authentic,’ and I say, ‘How can you be authentic? You’re German.’ ”

Ever since she learned to read, the 43-year-old Kwasny has been interested in aboriginal culture. She read May’s books and more: books about Wounded Knee, Custer’s last stand and the ongoing struggle for land rights. She has been a regular at German powwows since 1989. Born in Bavaria in an industrial area surrounded by towers and factories, there were few green areas where she grew up—mostly bushes and the odd tree. She remember longing for an intimate connection to nature and freedom of movement. She is convinced that Germans’ fascination with der Indianer comes from a lack of interaction with the natural environment in increasingly crowded, industrial cities.

Add the demise of the church, and you have a people also looking for a new way to connect with God. “After all these years, I found the freedom inside myself,” Kwasny says. “I don’t have to go outside. I can do this work because I can see them just as people, beyond the colour of their skin. People in Germany are trying to look for some closeness, a new religion, new way of thinking. The conflict is they have to find out that Native Americans are just people.”

They have to get past Karl May, in other words. His fiction, of course, makes no mention of the realities of colonization, oppression and discrimination that aboriginal people still face in Canada today. And local tour guides, in shuttling all those everyday Germans and hobbyists alike around Alberta, don’t typically schedule a visit to any of the homes of the 156,000 descendants of the First Nations, Métis and Inuit and who still live in the province.

That’s because the May fans and hobbyists are “fantasists,” says visual anthropologist Marta Carlson, a member of California’s Yurok tribe and a native studies teacher at the University of Massachusetts. If they knew the conditions in which a lot of natives live today, Germans would have no interest in recreating them authentically. “No one wants to be living below the poverty level on a [North American] reservation,” says Carlson. “It lacks a certain romance.”

Carlson is also troubled by the idea of North American aboriginals turning themselves into “cultural entrepreneurs” for Europeans’ benefit. “It feeds into and helps maintain the stereotype of Native Americans as living in the late 1800s,” she says. “It keeps aboriginal people in cultural stasis. And who has control over that image? The hobbyists.”

In her visits to hobbyist camps in Germany, Carlson has noticed two divides in the movement: east from west, and men from women. East Germans, she says, are more communal, less acquisitive of native products and tend to be more aware of and involved in aboriginal political causes. West hobbyist camps tend to be more materialistic, the regalia more magnificent and the participants more obsessed with authenticity. Carlson once attended a camp where you had to emulate the style of a certain tribe in a certain year: you had to park your car kilometres away, drag your stuff in on foot and you couldn’t wear glasses, contact lenses, socks or underwear. She describes hobbyism as very much a man’s game: the women are usually hidden away inside the teepees socializing while the men whoop it up outside. It was usually western German hobbyists who would tell her she didn’t know her own culture.

“German hobbyists consider culture a product, a kind of capital that they’re trying to acquire,” she says. “The effects of them doing our spiritual ceremonies… [they] have no idea what damage they could be doing. They could be unknowingly upsetting the balance of energy in our world.”

Carlson says that since first contact with Europeans, everything has been taken from North American aboriginals—their land, their freedom of movement, languages, their way of life. “Why can’t they leave us with our spirituality?” she asks. “I know people who have no problem sharing it, but it has to be done correctly. It can’t just be appropriated. It’s ours, and if you get upset with that, there is something wrong with you.”

Casey Eagle Speaker believes German interest in aboriginal spiritual practice is the beginning of realization of a Blackfoot prophecy that says that the four races of man…will one day come together in complete harmony.

Powwows are among the least contentious of hobbyist activities because they’re not religious or spiritual ceremonies. A powwow is a dance competition, a social event which may incorporate spiritual elements but whose purpose is akin to a county fair. A sweat lodge, on the other hand, is a sacred ritual akin to a church service where adherents go to find emotional and spiritual healing.

A Blackfoot creation legend says the sweat lodge was given to aboriginal people in trust, as a sacred gift. As the story goes, the Sun wanted to help a young warrior named Scarface. He led the young man into the first of four sweat lodges and showed him how to rub the smoke over his body on the right and left sides, purifying his body and wiping away his disfiguring scar. He also gave Scarface smudge, the sacred pipe, ochre, a forked stick for lifting hot embers and a braid of sweetgrass to make incense. Sun dances, ghost dances and pipe and naming ceremonies are also sacred rituals, usually hosted by a community or spiritual leader.

Casey Eagle Speaker, a Blackfoot elder from southern Alberta, believes German interest in aboriginal spiritual practice is the beginning of realization of a Blackfoot prophecy that says that four races of man, represented by the colours red, white, black and yellow, will one day come together in complete harmony. He points out that aboriginal people are involved in western religions, too.

“There has to be equality at some level to call upon the Creator for help, whether it’s at a church, sweat lodge or any other ceremonies,” he says. “Is there any wrong way to pray? No. These are spiritual practices, and every person is their own spiritual authority. As long as it is done with respect, there should be no boundary, no discrimination based on the shell you carry.”

As for German hobbyists, Eagle Speaker says it’s part of human nature to be interested in other people’s spiritual practices. “The Great Spirit exists in all people no matter what their colour or gender,” he says. “No person should be denied if they choose to be a part of a ceremony.”

When he lived in Canada, John Blackbird was alienated from his Indian family growing up, and as an adult felt too shy to participate in powwows. But since moving to Europe he has been forced to educate himself on Cree customs in order to sell his main product: himself.

He often feels frustrated with his role as a “dime-store Indian,” never being seen as a full person. But then he comes home to the prairies and sees the small “redskin” dolls with their chubby brick-red faces and fake buckskin breechcloths in the airport gift shop; the sweatshirts and mugs stamped with the faces of chiefs who were ignored, persecuted and imprisoned during their lifetimes.

He knows that if he looks for a job and an apartment, he will face a wall of racism. Canadian aboriginals’ wages are at the lowest rung of the economic ladder, lower even than what is made by other visible minorities. Even though they make up less than 3 per cent of the population in most provinces, aboriginals account for 18.5 per cent of the federal prison population, and their overall incarceration rate is almost nine times higher. On the whole, Blackbird’s two daughters could expect to have poorer health, lower levels of education and higher rates of unemployment as adults on their own land.

So he stays in Deutschland and dances for the NAAOG. He also writes for a local website and promotes the documentary film he finished in 2005. Entitled Powwow, it follows several male and female dancers as they perform a variety of dances from across a broad spectrum of aboriginal traditions. The film’s protagonists talk about the complexities of modern times, about residential schools, the church’s influence, the broken treaties, loss of land rights and the need to move forward.

“It’s hard being an Indian, but I love my Indian ways,” says a powwow announcer at the end of the film. Blackbird says he is trying to show Germans that aboriginal dances are thriving and evolving art forms, not the ancient rituals of an extinct people.

Once, as part of his promotion efforts, he described his documentary in an e-mail to a hobbyist organization as being about “Indian life.” He received a quick response informing him that the proper term was “First Nations,” that he would do well not to use outdated, racist terminology and that First Nations in North America never used the term.

“I am an Indian!” Blackbird shot back. “My friends are Indians, my family are Indians. We have always called ourselves Indians. I have a status card from the Canadian government that tells me I am an Indian. You have no right to tell me what I am.”

Originally from Montreal, Noemi Lopinto came west to become the managing editor of a small-town newspaper in northern Saskatchewan, where she first encountered the hobbyist movement. She now lives in Edmonton.