When Willa Gorman began working in the fibres area at Celanese in Edmonton in 1965, the chemical plant employed over 1,000 workers. “We worked with chemicals with absolutely no safety as we know it now,” she recalled in an interview in 2007 with the Alberta Labour History Institute. “[But] the union got involved, and the safety was really brought up much more and improved over the years.” Gorman retired in 2004 after 39 years as a unionized worker in Alberta. “We talk [today] about unions wanting money all the time; that wasn’t the case,” she says. “Often it was a safety or health issue that we would discuss for a long time.”

Gorman belonged to the Oil, Chemical & Atomic Workers Union, one of three organizations that would later combine to form the Communications, Energy & Paperworkers Union (CEP). The unionized energy workers were important players in a lengthy Alberta Federation of Labour (AFL) campaign that persuaded the Lougheed government in 1976 to pass the Occupational Health & Safety Act (OHSA). The Act gave workers the right to know about occupational health hazards, to participate with management in joint health and safety committees meant to reduce workplace risks, and to refuse unsafe work. The legislation benefited everyone who had a job in Alberta, whether unionized or not. The same can still be said today.

Critics of labour unions claim that unions are selfish institutions interested only in wringing higher wages for their members out of employers. But a closer examination of the history of unions in Alberta (and indeed throughout Canada and the world) shows that wages are only one focus of union efforts. Unions also emphasize safety, fair treatment of workers by supervisors, benefits for those unable to work because of injury or disability, and non-discrimination in hiring and promotion practices. The unions, above all, have fought—and continue to fight—for laws governing minimum wage, maximum hours of work, overtime pay and paid vacations.

All Albertans enjoy these protections and benefits. But unionized workers are best positioned to use grievance procedures and the courts to protect and advance workers’ rights, as well as to take immediate collective action. Noel Lapierre, chief shop steward for the CEP in Hinton, provides an example. “In 1980, 26 of my fellow workers lost their jobs because they refused to work in a terrible snowstorm,” he said. “When I learned about it I called on the shop stewards from each camp for an assembly that evening. Next day, no one worked in the woods. We made it a sit-down day so that the 26 guys could get their jobs back. We won after the one day off work.”

Such victories have a long pedigree in Alberta While many today see this as a one-class, one-party, one-ideology province, Alberta started off as Canada’s most progressive province. Its union movement began with the formation of locals of skilled railway workers in the 1880s. On June 14, 1912, Alberta workers gathered in Lethbridge to form the AFL. Lethbridge was a coal-mining centre at the time and coal miners represented the most militant workers in the province until the mines began to close after the Second World War.

Alberta unions hosted the Western Labour Conference in 1919 that sparked the creation of the revolutionary One Big Union and inspired the general strike movement that year. The province’s Labour Party had a cabinet member in the United Farmers of Alberta government elected in 1921. The Co-operative Commonwealth Federation, the forerunner of the New Democratic Party, chose Calgary for its founding meeting in 1932 because most of Canada’s socialist MPs at the time represented Alberta constituencies. The collapse of the Farmer and Labour political movements during the Great Depression and then the prosperity that followed the Leduc oil strike in 1947 transferred political power to the right-wing Social Credit party. The labour movement, though hampered by Social Credit’s anti-labour policies, continued to organize and to fight for social legislation.

One of labour’s first legislative victories in Alberta had been to convince the provincial government to establish the Workmen’s (now Workers’) Compensation Board in 1918. Two years later its campaign for a minimum wage for women bore fruit, followed by a minimum wage for men in 1936—making Alberta the first province to legislate a minimum wage for both sexes. The AFL’s persistent campaign in the 1960s for human rights legislation, for which it worked particularly closely with African-Albertan civil rights activists, was rewarded in 1966 when Ernest Manning’s government passed the Human Rights Act. Though that legislation forbade discrimination on the basis of race or religion, it lacked an enforcement mechanism. In 1972 labour’s efforts for such enforcement were recognized when Peter Lougheed created the Human Rights & Citizenship Commission.

In 1975 Labour Minister Neil Crawford gave Alberta’s Labour Board the right to require employers to grant maternity leave. He paid tribute to the labour movement for having already won this right for many of its members, saying that their success had inspired him to extend “the benefits of this progressive type of thinking” to more women. Labour continued to fight for maternity leave to be universal rather than something one fought for at the Labour Board, and in 1980 the Lougheed government passed legislation to that effect.

Picket sign of Alberta construction workers, 1984. (Courtesy of Alberta Labour History Institute)

The Ralph Klein years, with their emphasis on reducing government services, created an “Alberta Advantage” for the better off and disadvantages for everyone else. But Klein’s dizzying cuts in 1993 and 1994, which caught the labour movement as a whole off guard, ground to a halt after the humble hospital laundry workers of Calgary said “enough is enough.” These workers accepted a 28 per cent cut in their wages only to be confronted within a year with the government’s determination to privatize their jobs. On November 14, 1994, about 60 laundry workers at Calgary’s General Hospital, members of the Canadian Union of Public Employees (CUPE), launched an illegal strike. The next day they were joined by laundry workers at Foothills Hospital, members of the Alberta Union of Provincial Employees.

The strike quickly escalated to include 2,500 workers in six hospitals and nine nursing homes. CUPE activist Jimmy Arthurs recalled: “We had great support from people driving to work. Lots of tooting of horns and waves—it was just unreal the support we got from the community… They had seen the devastation the Klein government created with their cutbacks, their slash-and-burn tactics. So there was a great understanding of what… the laundry workers were suffering. Here they were, some of the lowest-paid workers in the industry, and their jobs were going to be contracted out to the private sector with no rights or benefits granted to them, no retraining.”

Many labour activists wanted the AFL to launch a general strike in an effort to reverse the Klein cuts. The government, fearing such escalation of opposition, quickly provided a financial package to the Calgary Regional Health Authority so that it could delay contracting out. Labour’s resistance and the public’s support seemed to shake Klein’s resolve. The premier had always attributed his political success to figuring out which way the parade was going and getting out in front of it—but this time, the parade changed direction.

Albertans also enjoy benefits that come from Canada’s having a resilient labour movement. Though many Canadians don’t know it, we largely have the unions to thank for universal medicare. The Conservative government of John Diefenbaker, sympathetic to the voluntary medical plan that Manning implemented in Alberta in the early 1960s rather than to the universal one that Tommy Douglas bequeathed to Saskatchewan, established the Hall Commission on Medical Insurance in 1961. While the Canadian Medical Association and the Canadian Chamber of Commerce deluged the Hall Commission and its Conservative appointees with arguments for voluntary insurance, the trade union movement, almost alone, provided the ammunition for compulsory insurance.

An important argument of supporters of private insurance was that union members already enjoyed health insurance coverage through their union-negotiated work plans, but the Canadian Labour Congress and its provincial affiliates poured cold water on this claim by showing the loopholes in private insurance plans. They argued for a public program that covered everyone regardless of where they worked—and even if they were unable to work.

Organized labour has played an important role in winning almost all of the social programs that so many of us take for granted today, from Old Age Security to the Canada Pension Plan, and from employment insurance to maternity benefits. Today the labour movement leads the fight for universal daycare, improved old-age pensions, housing as a social right and the extension of medicare to include home care, dental care and pharmaceuticals.

While movements for civil rights and gender rights originated outside the labour movement, many of their activists, working inside the labour movement, compelled employers and governments alike to end discriminatory practices. In 1992, for example, nurse Susan Parcels, supported by the United Nurses of Alberta, won court victories that forced Alberta employers to provide the same benefits for mothers on maternity leave that employees on other forms of leave receive.

UNA’s illegal strikes in the 1980s established that nurses were professionals who merited decent pay and working conditions. Women in public sector jobs generally have achieved similar victories since the 1960s, when unionization in the public service became more common. Indeed, a larger percentage of Canadian women than men are unionized today thanks to higher rates of unionization in the public sector than the private sector. (And while the rate of union membership among Canadian men fell between 1997 and 2010, union membership among women increased.)

Unions fought to create a minimum wage, to limit the work week, to mandate overtime pay and paid vacations—benefits that all citizens now enjoy.

Aboriginal workers, while underrepresented in unions relative to their population, have also benefited from unionization. At Suncor in Fort McMurray, for example, “there was prejudice in our workplace,” recalled Jim Cardinal, an Aboriginal union activist interviewed by the Alberta Labour History Institute. “I always [got] the dirtiest job… it happened over and over again. [But the] union has fixed that over at Suncor, that’s changed now.”

Landed immigrants and new citizens are sometimes wary of unionization because their limited language skills leave them vulnerable when employers retaliate. But some immigrant workers have defied the odds, successfully unionizing and striking when employers have treated them poorly. Predominantly non-white Lakeside Packers workers in Brooks, for example, had had enough before they went on strike in October 2005 and endured a bitter but ultimately successful three-week confrontation. As Peter Jany, a Sudanese immigrant and United Food & Commercial Workers activist, explained, the workers unionized and struck the company to demand to be treated with dignity. “Some people get damage in their backs, shoulder, leg, everything,” he said. “But the company wouldn’t accept [this]. We told them, ‘You have to slow the speed down, because the big problem is the speed.’ They say business is business… They treat us like garbage.”

Temporary foreign workers (TFWs) have fewer rights than citizens or landed immigrants. The government considers TFWs good enough to work in Canada but not good enough to be eligible for citizenship. Many of these workers report feeling afraid that efforts to unionize or even complain will lead to their being fired and deported. In 2009, 65,478 TFWs toiled in Alberta, almost 2 per cent of the entire provincial population and far more proportionately than were working in any other province. In 2007 the AFL hired Yessy Byl, an Edmonton lawyer, to serve as an advocate for TFWs. Within six months she had fielded 1,400 inquiries and taken on 123 cases. Byl investigated a large number of employers who hire TFWs and found that 60 per cent had violated at least one requirement of the Employment Standards Code, the Occupational Health & Safety Act, or both.

The best evidence that unions continue to benefit all citizens is perhaps seen in their fight for social equity. Globally, the evidence is clear that the higher the rate of unionization, the better the social legislation and the narrower the income gaps among citizens.

Scandinavia provides the best examples. In 2003, over 70 per cent of employees in Sweden, Denmark and Finland were unionized. While Norway’s comparable figure was 53 per cent, about 70 per cent of Norwegian employees were covered by a union’s collective agreement. By contrast, 31.5 per cent of Canadian workers were unionized that year, as were 25 per cent of Albertans. In the US, a mere 12.4 per cent of workers are unionized. The correspondence between high levels of unionization and a fairer distribution of wealth is dramatic. The Gini coefficient—a measure of overall distribution of wealth in which 1 signifies that all wealth is in the hands of one household and 0 signifies no income gap among households at all—demonstrates that the Scandinavian countries are the world’s most egalitarian. As reported in the 2011 CIA World Factbook, Denmark, with a Gini coefficient of 0.232, was almost twice as egalitarian as the US at 0.45 and significantly better than Canada at 0.321.

Norway, which has a Gini coefficient of 0.25, provides an interesting contrast to Alberta. The country has just one million more residents than our province. Both economies rely heavily on the extraction and export of fossil fuels. But while Alberta has mediocre social programs relative to other Canadian provinces—particularly daycare and home care for seniors and the disabled—Norway’s social programs easily trump those of all Canadian provinces. Its medical insurance plan covers not only doctor visits and hospital stays but also free dental services for people under 20 and over 65, home care and the full cost of prescription drugs for chronic conditions. Public old-age pension plans provide most retirees with an income equalling 60–70 per cent of the peak income from their work years. Parents are guaranteed 80 per cent of their wages for one year after the birth of a child (they can split the time) and nearly free daycare and after-school care until the children turn 12. The education system charges no tuition from preschool through to post-secondary.

Norway’s labour movement played the biggest role in convincing Norway not to follow other European countries and North America along the path of tax reduction, social program cuts and greater privatization of services. The Campaign for the Welfare State (CWS), a union-initiated organization that also involved social justice and environmental movements, drew up a “people’s agenda” to counter the free-market policies of the conservative Norwegian government of the turn of the century. Once the CWS had produced a manifesto of social and environmental demands, it asked all political parties to sign on. Three opposition parties consented. The Campaign required these parties to promise publicly before the next election that if they won a majority, they would form a coalition government committed to people-first policies. The three parties, which included a social-democratic party, a socialist party and an environmental party, won 60 per cent of the vote in 2005 and formed the government. They were re-elected in 2009.

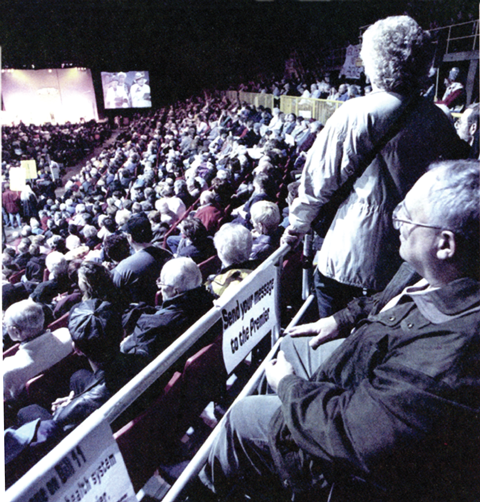

Thousands of Albertans gather in Edmonton in 2000 at a union-led rally against Bill 11 and private healthcare. (Courtesy of Alberta Labour History Institute)

But does such equality make people happy? Or are nations such as the US and UK, with their emphasis on individual freedom, the countries for Canada to emulate? Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett, two British social researchers, argue the former. Their 2009 book, The Spirit Level: Why More Equal Societies Almost Always Do Better, shows that the most egalitarian among advanced capitalist countries boast lower crime rates, fewer mental health problems, less obesity and fewer infant deaths, while their citizens report greater satisfaction with their lives. Ironically, the wealthiest 20 per cent of individuals in the US—hiding behind iron gates to fend off potential criminals—fare more poorly on all social measures than the poorest 20 per cent of Norwegians. This suggests that the social equality that union-rich societies enjoy indeed benefits all citizens.

As the AFL celebrates its 100th birthday this year, local unions face many challenges. Alberta is the province with the lowest percentage of unionized workers—its 25 per cent rate compares to 39 per cent in Quebec and Newfoundland and 38 per cent in Manitoba, the three most unionized provinces.

This low rate is thanks to provincial legislation that actively discourages unionization. For example, unionized employers who want to be union-free can simply change their company’s name, which voids pre-existing contracts. Workers then have to try to recertify the union. This practice has decimated construction unions in particular. So-called “company unions”—unions that are tools of management rather than grassroots-controlled institutions—have been allowed to operate here and make life difficult for genuine unions.

Agricultural workers, who have an appalling occupational death rate (13 farmworkers died on the job in Alberta in 2009 alone), have been denied altogether the right to unionize by the province even though Supreme Court decisions in other provinces have established that such legislation violates workers’ rights under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

Klein’s departure from Alberta politics created some hopes in the labour movement for a new openness to workers’ rights. But within months of his election win in 2008, Ed Stelmach tabled legislation that limited the ability of construction workers to join a union and stripped paramedics of their right to strike. His government’s efforts to shrink the public sector, including its campaign to close Alberta Hospital, mobilized labour opposition, which proved partly successful in the Alberta Hospital case. And while Alison Redford within days of becoming premier restored education funding that Stelmach had cut, labour organizers soon became wary about her commitment to tax reform or workers’ rights.

All Albertans suffer when the labour movement is weakened. If we work for an employer, we’re vulnerable to mistreatment if no one can stand up for us. We suffer when public services deteriorate—and Alberta today spends far less as a percentage of GDP on public services than any other province. And, rich or poor, we all suffer from income inequality. A 2012 report by Action to End Poverty in Alberta and Vibrant Communities Calgary pegs the annual external cost of poverty to Albertans at between $7.1-billion and $9.5-billion just in increased law enforcement and healthcare costs. This doesn’t include direct costs such as social services. And the income gap in Alberta is widening faster than in any other province.

The start of the AFL’s second century is an opportunity to recall the benefits that unions have brought to all Albertans, regardless of social background. It’s also a chance to recognize the task that remains for all Albertans who hope to build a safer, healthier, more equitable society. Ultimately, unions are here to serve all citizens. Citizens need only make it possible for unions to continue to serve as a visionary force.

Alvin Finkel is a professor of history at Athabasca University and the author of Working People in Alberta: A History (AUP, 2012).