My husband’s childhood home was on a crescent that curved down a long hill overlooking the North Saskatchewan River in Edmonton. In the late 1970s, on every visit, we noticed down the block an undistinguished 1950s bungalow being renovated. This construction project was not merely cosmetic; the entire house was changing, taking on a character and profile different from any in the neighbourhood. We watched the silhouette of the West Coast post-and-beam house growing there, fascinated by its elegance and style. We had no idea who was doing the work; we just knew it as the Grotski house, and that its new design seemed to merge outside and inside with huge sheets of glass under a side-facing sloped roof.

I did not know then that the Albertan architect Douglas Cardinal would become a household name, synonymous with a distinctive combination of curves, light and stone—building components, yes, but also echoes, hints of the mysteries of nature that most man-made structures ignore or deliberately shut out.

When I meet Douglas Cardinal in 2013, at his signature building, the Canadian Museum of Civilization (now renamed the Canadian Museum of History), I am surprised that he is, unlike his structures, almost angular, an imposing man in stature and demeanour. His face seems carved with sternness, until he smiles. But that smile is fleeting, as if he were unwilling to show either vulnerability or pleasure. This man reads everything around him with studied intention.

We introduce ourselves at the entrance of the museum, on the banks of the Ottawa River in Gatineau. This iconic landmark, more than any other structure besides the Parliament Buildings and the Peace Tower itself, stands for what we know we are as Canadians. The site itself is beautiful, but the building is breathtaking, a series of stacked and sinuous curves that suggest and replicate the rivers it pays homage to. It seems Cardinal could probably rest on his laurels forever as the creator of that vision.

We walk toward the magnificent open cliff of the Great Hall, and are stopped by a guard who asks for our tickets. Cardinal does not flinch but reacts matter-of-factly. “I’m giving her a tour; I’m the architect.”

The young attendant looks puzzled, then mutters okay, and it is all I can do not to shout at him. “Do you know who this is? This man created this place!” But I say nothing, and we proceed, with Cardinal shrugging when I express incredulity that he is not recognized. His history with Canada’s flagship museum has not always been smooth, even after the place was built and opened. He tells me that for years he was not invited back or asked for input on the building’s condition, and that he and Victor Rabinovitch (director from 2000–2011) rarely spoke. When I ask why, Cardinal shrugs and says, “Politics. The new director, Mark O’Neill, first thing he did was call me up and say, we have to get together. Here we are, this museum is the most popular Canadian icon, and we don’t have a relationship? Let’s talk.”

Such elemental forbearance seems to be intrinsic to Douglas Joseph Cardinal, OC, recipient of more than a dozen honorary doctorates and countless other distinctions, including the Gold Medal of the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada and a Governor General’s Award for Visual and Media Arts. He is a household name, if not necessarily recognizable as an architectural rock star.

Cardinal is a native Albertan. Born in Calgary to parents of German-Metis (mother) and Aboriginal (father) ancestry, he attended St. Joseph’s Convent residential school near Red Deer, where he soaked up music, literature and drawing, getting excellent marks and serving as head altar boy. “My mother and father, because they had to deal with so much racism, decided to keep me from that,” he says. “I went to a convent school.” The contradiction of that statement does not seem to unsettle him. “Oh, there was racism, but I figured out that the way to survive was to excel, to do exactly what was expected, and more.”

He went on to study at UBC’s School of Architecture, where his insistence on using curved lines did not meet with approval (this was the conventional 1950s), and he pulled out in the third year of his program. “The director of the program said I had the wrong family background, that I’d never be an architect.” He left for the University of Texas at Austin, where he says each individual was supported to develop himself.

Back in Alberta, Cardinal began to work as an architect, first making a living by designing rumpus rooms and ordinary houses, until in 1968 he was commissioned to build St. Mary’s Roman Catholic Church in Red Deer.

If Cardinal has any pedagogical father, it is surely Rudolf Steiner, best known for founding Waldorf education, but whose architectural work as well refused traditional constraints, especially the right angle as key to building. Steiner’s “anthroposophy” (a mixture of idealism and theosophy) underpins Cardinal’s adamant insistence on connecting the spiritual to the structural, the visionary to the physical.

But his relationship to Father Werner Merx, the Oblate priest who worked with Cardinal on St. Mary’s church, was also foundational. Cardinal says he imagined embodying in brick the vision of Father Merx, who wanted a clean, uncluttered space, evocative and open. “Every day Father Merx would look at what I had done and criticize my drawings, so when I put all the shapes of the building together I did it exactly the way he wanted it to function. The form grew out of the function.”

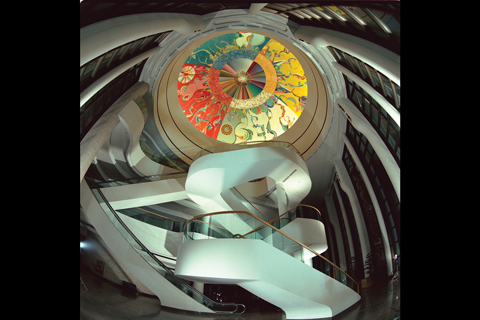

Canadian Museum of Civilization

However that sounds, Cardinal’s translation of idea into physical structure is not utilitarian. To Cardinal, “function” is what happens in a building, while form is the spatial transfiguration of that activity’s aesthetic yearning. He considers how people will feel in a structure, and how outside forces, sun and wind, will act on it. St. Mary’s is a naked church, where belief and worship curl together in a cauldron of brick both sublime and subdued, what Cardinal calls a “natural organism.” The altar hovers under an almost planetary shaft of light, and the play of illumination and darkness throughout the building echoes Stonehenge as well as Chartres.

Cardinal’s buildings are generated from the inside out rather than the outside in, and their actualization is often challenging. They are seldom rectilinear, never square. He has been accorded the designation of curvilinear architect, one whose structures don’t follow a grid or replicate square boxes. Over and over Cardinal mentions to me how important it is for an architect to work with his clients. His buildings, he says, “have a soul.”

“Most places don’t serve the people in them,” he says sadly; they fail both aesthetically and functionally, directing people, confining them, limiting their view. His desire is to make buildings that connect people to their environment rather than separate them from it.

His complicated aspirations seem part of the crux of why Cardinal is considered “difficult.” Notwithstanding his success (he can take credit for more than 100 built projects), Cardinal’s path has never been easy. He has a reputation for going over budget, for taking longer than anticipated on timelines and for insisting on the impossible. As if curved walls weren’t enough, he also includes sightlines, solstice lines and sculptural undulations. Despite his groundbreaking work with technology—Cardinal was one of the first architects to use computers to calculate structural accuracy—those loops and meanders are not always easy or cheap to produce.

And perhaps, too, Cardinal’s rather prickly place within the ranks of “famous architects” has to do with his work’s political inflection; activism and architecture are an odd combination, but Cardinal has always juggled them. Early in the architect’s career, Fred Colborne, Alberta’s Minister of Public Works between 1962 and 1967, gave Cardinal a lot of work and divulged that he wanted Cardinal to help First Nations people take on what were in the 1960s the severely racist policies of the federal government.

As someone who had been involved in the human rights movement when he lived in the US, Cardinal is an experienced reader of political discourse. He jokes about how Texans didn’t quite know how to respond to his accent: “The weirdest thing was that I had a Canadian accent, which sounds to them like a Harvard accent. When I was there, it was totally segregated. Black students, Arab students, and I was a foreign student. But what was so different for me, in Texas at the time, they were trying to be very white. They would try to teach their kids to get rid of the southern accent because they thought of it as a black accent. Kids would be taking elocution to speak in a more cultured accent. And I sounded cultured, so I experienced reverse discrimination.”

Cardinal talks with enormous respect about Pierre Trudeau, whom he first met while advocating for First Nations issues. In that way, he came to Trudeau’s attention and when the time came to select an architect for a national museum, Trudeau knew Cardinal possessed powerful prescience. “He told me that he wanted to establish symbols of nationhood: a constitution to enshrine our rights; a gallery to enshrine the arts; a museum to enshrine our cultures. He wanted these symbols to be in place.”

But not all of their encounters were uncomplicated. “When I got the commission, I had to fly to Ottawa,” Cardinal remembers. “For 10 years I had negotiated with Trudeau and Canada for rights for the First Nations. But I thought, well, I have this big commission, so I cut my hair, put on a three-piece suit. Trudeau walks in, looks around the room, says to his minister, ‘Where’s that Indian architect? I gave him the most important commission in the country and he doesn’t even come to shake my hand?’ The minister says, ‘Prime Minister, he’s right over there.’”

Cardinal says Trudeau told him, “‘I didn’t recognize you without all your regalia.’ I said, ‘Prime Minister, I haven’t changed a bit. I am exactly the same inside.’ And Trudeau said, ‘If you make the same commitment to my vision as you did to your people, we’ll have a good museum.’ ”

Cardinal pauses, “He was my best client.” When the architect brought his models and drawings to Ottawa, Trudeau wanted to know and understand every aspect of the design. Cardinal remembers him saying, “This is good. I can fully understand what you have done here. What I wanted was a building that related to nature, to our dramatic environment. This reminds me of taking a canoe trip, seeing the large swells. I would rather have a symbol in the capital that reflects the Canadian landscape than a symbol of any one culture. Anyone who has an affinity to the land can relate to this building.”

Cardinal is less sanguine about the long, hard grind that it took to concretize the vision, about his quarrels with “political reality” and especially with Brian Mulroney, the prime minister who opened the Museum of Civilization. “I was not popular with the government because, for example, although Trudeau established a separate Crown corporation, which was independent and answerable to him, the Conservative government put the corporation under Public Works. So then I was met with all the political problems.” He claims that the support of Joe Clark and the Alberta caucus, especially Don Mazankowski, actually helped bring the project to fruition.

“It was a lot of work. When it opened, people loved it, there was a major celebration, but I was rather exhausted at the time. I had such a time; the government of the day tried to take the stone off and put on aluminum siding, wanted to put lino on all the floors, they were trying to cut the cost. I had to deal with an awful lot. The current director says, ‘Your generation gave you a rough time; it is my generation that appreciates it.’ ”

The result is spectacular, and that Canadians have lived with it for almost 25 years now (the museum opened in 1989) does not diminish its breathtaking effect. The light, the curves and the organic feel of the structure suggest a prairie spaciousness that is to my eyes profoundly Western.

Cardinal explains that he was trying to capture “the expansiveness of the country. You can’t define it. The challenge was how to design the building to respect the site. In most Canadian cities, nobody really addresses the power of the river, or people’s relationship with the river. We don’t even have that in Edmonton or Calgary, with the Bow River and the North Saskatchewan. There are parks, but nothing that says, Here’s the river. European cities embrace their rivers. I wanted people to be able to see the Parliament buildings across the river, to see the historical buildings on the other side of the river. That was important.”

This reading of site and situation that Cardinal brings to his buildings has been the cause of no small commotion, most especially with the controversy over the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian. In a conflicted series of twists and turns, Cardinal won the commission for that museum—the last one to be built on the Mall in Washington—and then entered into what could only be described as a long war that was even more draining than his struggle to encapsulate Trudeau’s national aspiration. While his conceptual design met with enthusiasm and he was chosen over all the architects in the US, the bureaucracy of Washington was even more byzantine than Ottawa’s.

A series of skirmishes over Cardinal’s design combined with delays to his financial disbursements led to increasingly acrimonious struggles that ultimately led to his being let go from the project. He says the root cause was a resistance to the unusual plan he was trying to implement, derived from “vision sessions” with 16 tribal elders who came to Washington and recounted their family and originary stories. The Smithsonian claims that Cardinal did not work well with the Philadelphia-based firm of Geddes Brecher Qualls Cunningham, the project managers, and that there were squabbles about expenses and money. The Smithsonian was reluctant to intercede in the dispute, Cardinal held his drawings hostage, and the Smithsonian fired both Cardinal and GBQC, followed by a series of suits and countersuits on multiple sides. Quelle désastre. The Smithsonian hired a different team, and Cardinal was sidelined.

But it seems his inspiration had already settled onto the last-remaining museum space on Washington DC’s mall. The replacement architectural team’s attempts to modify Cardinal’s design ultimately met with disapproval and a directive to work as much as possible with the original concept. While Cardinal was never officially reinstated as the architect, anyone who has seen his work recognizes his signature immediately: the National Museum of the American Indian, while it may not necessarily be a Cardinal building, nevertheless looks like a Cardinal building, its curves and rock-face structure as indelibly recognizable as the paleolithic art of Lascaux. That may have been the tipping point for his US experience. “I wanted to design a powerful, female building that is nurturing and protecting. Long cantilever over the main entrance. Shaded.” Cardinal did not attend the 2004 opening, but he has been inside since, and he is vocal about the design’s compromises. And while he says he is not bitter, he is clearly very pained about what happened to his vision and the vision of the elders that he so much wanted to actualize.

Cardinal’s base now is his home, an ordinary house that he rents on the banks of the Rideau River. His team of young architects and designers are settled in his cosy walk-out basement. There’s not much space, but they work together in a hum of energy that combines suppressed excitement with contentment. They don’t make a big deal out of being part of the atelier of a master, but they know, it is clear, that they are apprentices to ideas bigger than the screens of their computers, and much bigger than the fragments of stone or brick that together comprise buildings. Because Cardinal was one of the first architects to use computers as integral tools in the design process, no one on his team is afraid of technology, and the programs they work with are so sophisticated that they can calculate infinitesimal measurements.

The architect’s recent work reflects a quiet industry that he hopes will eventually take him back to Alberta. The Aanischaaukamikw Cree Cultural Institute in Ouje-Bougoumou, Quebec, which opened in 2012, is an open-armed, ship-like structure serving as a museum and gathering place. Ground has been broken for the Gordon Oakes-Red Bear Student Centre at the University of Saskatchewan; design for the Long Point First Nation School in Winneway, Quebec, is in process; and the Regina Entertainment Stadium is coming to visualization. “I really want to do more work in Alberta,” Cardinal says. “I am a little tired of learning all about political complexities. I feel that people out West are more real.”

Whether that is the case or not, Cardinal’s shapely buildings express contours more undulating than angular. There is a feminine sensibility to the spaces he invites the visitor to enter, and he talks about his buildings as defying the expectations of male order based on conflict. He explains, “Most buildings are readily definable from the outside; this building [the Museum of Civilization] is not like that. Guys want you to define space. They want to know where they are at so they can defend it. This space confuses them. What’s around the corner? They don’t know.”

Cardinal has himself engaged in tough fights, court pugilism and plenty of scraps. Beneath his gentle exterior lurks a version of warrior, a powerful strength that has carried him through almost 80 years, four marriages, many moves, multiple divorces, children, grandchildren, great-grandchildren and, not least, buildings. He concedes he has had to fight with his own confrontational ambition, and he says he is no longer interested in fighting. He attributes much of his newfound peacefulness to his Basque wife, Idoia Arana-Beobide, saying, “I am glad I am married to a Basque, but they are the most stubborn people I have met in my whole life.”

This could be a case of the stubborn calling out the stubborn. Still, Cardinal’s refusal to adhere to linearity or predictability is not simplistic, and he says it reflects his family heritage. “I got that from my mother. My mother is part German; her father was a homesteader at Madden. She grew up on the farm there. She was always exposed to culture, music, and she was a nurse, actually a supervisor at the hospital at Ponoka. She was already established when she met my father at 26. As a professional with a strong European background, she had to endure an awful lot of crap. She grew up in a very racist society, a society where women were not respected, they were non-persons. My father, being a First Nations, was accustomed to a matriarchal society where women are the centre of the family. They were always respected, always had more power. She met my father and moved to a log cabin in the Porcupine Hills. They were totally different people: she was very German and he was very First Nations, he was a hunter and a trapper. I loved and admired them both but I learned two whole different world views from them. One view of harmony and nature and respect and love and caring from my father, and the other one from my mother about serving people.”

“So when I look at my architecture, it is more Ionic [delicate and scroll-like] than Doric [heavy and simple]. I think that buildings should be nurturing places that show a concern and respect for people. That is generally my approach to architecture. I suppose I was brought up to believe that the soft power of love is much more powerful than the hard power of force.”

“So I think that when you love your work and love people, life can be very rewarding. If you take the other approach, and try and play these power and control games, then you live a life of stress and aggravation. I wanted this building [the Museum of Civilization] to be one of nurturing and caring. If you have that, no matter how you put it together, then people get it, and they enjoy the space.”

Douglas Cardinal has changed since his Edmonton days, and he says he has “learned a lot.” When I ask him now, in 2013, about the house on the suburban crescent overlooking the North Saskatchewan in Edmonton, he remembers mostly how the Grotskis loved the way he used cedar to intensify the natural setting of the property.

But I remember standing on the sidewalk and trying to read the secrets of that house. There was something there that I could not put my finger on at the time. It was implacable, mysterious, alluring. At that time, I thought it was design. Now I would call it poetry. Douglas Cardinal’s poetry.

Aritha van Herk is a prolific author, teacher and critic, and a member of the Royal Society of Canada. She lives in Calgary.