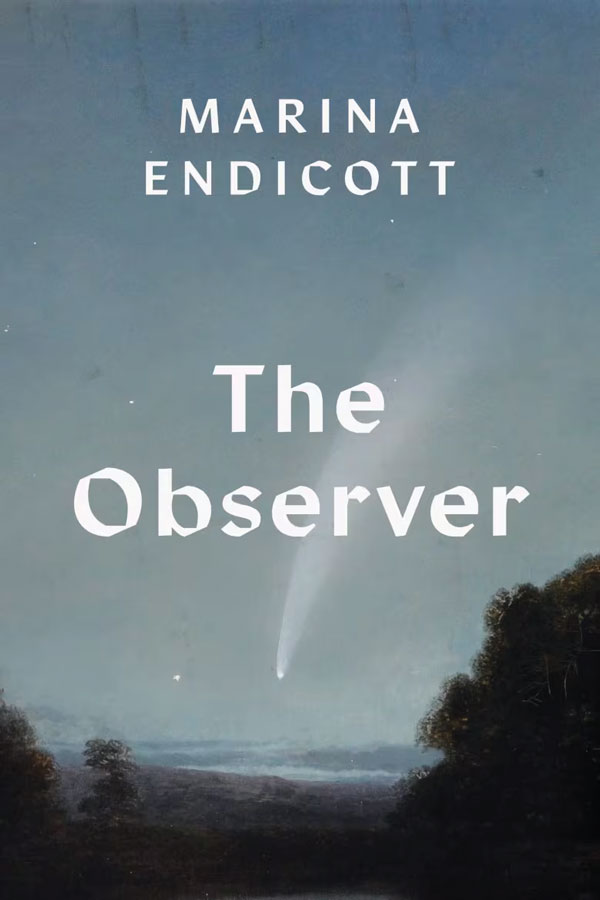

One metaphor for literature is that it is an act of staring into the unknown—into the abyss, the bleak, unending and unintelligible universe that stares back at you if you stare at it too long—to refract the darkness and render it comprehensible. To better know the vastness of the night sky, in other words, we write a comet blazing through it.

The Observer, the new novel from Marina Endicott, uses this metaphor to illuminate the “country dark” that our protagonist Julia, a dramaturge, finds herself in during her partner Hardy’s first posting as an RCMP officer. The novel fictionalizes real events that happened in Mayerthorpe, northwest of Edmonton, and is partly autobiographical: Endicott was a dramaturge whose husband moved to Mayerthorpe in his first posting with the RCMP. The town’s name became synonymous with tragedy when in 2005 four RCMP constables were murdered there. Eleven years later a firefighter and the son of the former Mayerthorpe mayor was charged with a spree of arsons, including one that consumed a bridge. Endicott writes around these events rather than about them, and the major tragedy only appears from a distance as a postscript. The Observer is more a prequel that depicts the ineffable rural despair in which these events were situated. “Here I was afraid or in awe of elemental forces,” Endicott writes. “Nothing was directed at me; I was a mere speck.” Within this milieu, throughout their first spring in their new home a comet dazzles in the sky, and as it reappears throughout the novel it epitomizes these characters—two specks of light amid the dark.

With Mayerthorpe recast as the town of Medway, Endicott captures the gritty minutiae of small-town life. A hotel reeks of the “beery death of hope.” Bar brawls and suicides underpin a dull quietude with an ambience of “black despair.” Julia soon works at a newspaper, so we gaze through the lens of reporters and police officers. “A van hit a tanker on the way up to Ridgeway and everybody worked all night matching parts to bodies,” she writes. The newspaper shares the name of the novel, implying that Julia can observe but not fully explain the darkness that surrounds her, just as the newspaper cannot, just as this novel cannot. Instead, we get subjective observation—the blazing comet against a black backdrop.

This frames the novel but also wounds it, engendering the perception that Endicott is lampshading—acknowledging up front the novel’s limitations—to skirt its ostensible subject. Julia is a writer who watches Fellini films and studies esoteric philosophy. Hardy, the policeman, is also a poet and former reporter, and they befriend a celebrated poet—as though Endicott is most comfortable telling the story through the lenses of people who write and attend the symphony. Others are provincial caricatures. When Julia makes dinner—“glazed salmon, mashed sweet potatoes and Brussels sprouts sautéed with lime”—you know how the paragraph is going to end: her guests aren’t sophisticated enough to appreciate it. “They ate the whole chocolate cream pie, though.” It betrays a disinterest toward the people most implicated in the novel’s themes—and therefore most able to illuminate them.

Endicott doesn’t allow her characters to become the abyss they stare into. We can’t comprehend the darkness without the guiding light of subjectivity, but the opposite is also true: without gazing into the night sky, how can we appreciate

the comet?

Robbie Jeffrey is a writer in Edmonton. His article about rural Alberta’s opioid crisis was in Best Canadian Essays 2019.

_______________________________________