Part 1: Following the populist playbook

Danielle Smith rode a wave of Alberta populism to win the United Conservative Party leadership on the sixth ballot. She is a new and potentially disruptive force in Canadian politics. “No longer will Alberta ask permission from Ottawa to be prosperous and free,” Smith said in her acceptance speech October 6. “We will not have our voices silenced and censored. We will not be told what we must put in our bodies in order to work or to travel. We will not have our resources landlocked or our energy phased out of existence by virtue-signalling prime ministers.”

Alberta politics includes a long tradition of populism: a belief that ordinary people are being kept down by an elite. That elite might be the federal government, global environmental activists, scientists or eastern Canadians. Populist leaders often rise to power by offering simplistic but grand plans, like Donald Trump’s promise to “build a wall” along the border with Mexico.

Smith’s win in the UCP leadership race follows the populist playbook. She positioned herself as an outsider, sided with the protesters angry about COVID-19 restrictions and vaccine mandates and promised she would put “Alberta First” and fight Ottawa with her Sovereignty Act.

The UCP leadership race was primed for a populist to win.

The party’s membership is predominantly located outside Calgary and Edmonton. Unlike many other parties’ rules for electing a leader, there was no weighting of votes by electoral district to ensure the new leader has support from across the province. Each vote was counted equally. Anti-establishment populist sentiment is strong in rural Alberta.

Being seen as an outsider is important for politicians who want to ride a populist wave into office. Only an outsider is able to make credible claims they will sweep away the elite. Smith was the only candidate for UCP leader without a seat in the legislature; many served in former premier Jason Kenney’s cabinet. For party members angry at the Kenney government, her claim to be an outsider was an asset.

Smith is not new to Alberta politics, though. She was leader of the Wildrose party, losing an election in 2012 and then crossing the floor to the government in 2014, ending that chapter of her political career. She then spent six years as a radio talk show host.

During the pandemic, Smith criticized COVID-19 restrictions and vaccine mandates; her views played a role in her departure from her radio job. In her statement when she left, she said she was “gravely troubled by how easily most in our society have chosen to give up on freedom.”

Alberta stands out in Canada for its relatively low public support for public health measures and negative assessment of the province’s pandemic response. As protests over COVID-19 mandates turned into the so-called freedom convoy, UCP supporters were more likely than other Albertans to approve of that protest movement. Smith was able to mobilize support from Albertans angry about public health restrictions. One of her earliest campaign videos stated: “What happened over the last two years must never happen again… Let me be clear: As your premier, our province will never lock down again.”

While the backlash over COVID-19 restrictions gave Smith momentum to launch her leadership bid, her Alberta First stance solidified her as the leading candidate in the race.

The movement that fuels support for the Sovereignty Act isn’t your grandpa’s Alberta alienation.

There is a widespread belief among Albertans that the province is not treated fairly or given the respect it deserves. Although a minority of about 20 per cent, separatists are a persistent force in Alberta politics.

Many UCP supporters have been frustrated that Kenney’s efforts to eliminate the federal carbon tax, renegotiate the equalization formula and build pipelines to tidewater have not been successful. Smith’s strategy was to adopt a more radical stance on Alberta’s place in Confederation. The centrepiece of her Alberta First platform is her proposed Alberta Sovereignty Act, which she has promised will be her first priority as premier.

The Sovereignty Act was first proposed as part of the Free Alberta Strategy. The document argues that Canada has “expropriated” Alberta’s wealth for decades and has “breached its constitutional agreement with Alberta.” It advocates for the Alberta legislature to grant itself the power to refuse to enforce federal legislation or judicial decisions that, in its view, interfere with provincial jurisdiction or attack the interests of Albertans.

Most of the other candidates for the UCP leadership, Kenney, and constitutional experts have criticized the proposal as blatantly unconstitutional and destabilizing to investment in the province. Despite these criticisms, the proposal is popular with Smith’s supporters.

Smith is a potentially disruptive force in Canadian politics. She has to hold together a divided caucus, satisfy her supporters and position her party for a provincial election in spring 2023. If she’s able to unite her caucus to pass the Sovereignty Act, the courts will almost certainly strike it down as unconstitutional, leaving Smith fighting against the Canadian constitutional order during the provincial election.

It remains to be seen whether Smith’s time in office will be a brief interlude, or the start of a significant challenge to national unity.

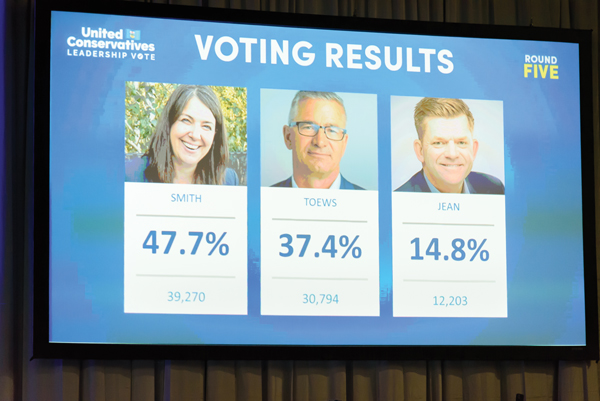

On October 6, 2022, Danielle Smith ultimately edged past Travis Toews, with 53.77 per cent of the 84,593 ballots cast by UCP members. She won the leadership of the UCP party, and by default, the premiership of the province. (Will Geier for Alberta Views)

Part 2: Origins of the Sovereignty Act

Alberta alienation has been around more or less since the province was formed in 1905. Agrarian populism has morphed into extractive populism; anger about the federally regulated banks has morphed into anger about equalization; rejection of the central Canadian narrative of the country has been a constant. While there is much continuity in the presence and expression of Alberta’s alienation, the movement that fuels support for the Sovereignty Act isn’t your grandpa’s Alberta alienation.

What has developed over the past three decades is an overt effort to cultivate a regional identity grounded in a shared political ideology. What is distinctive about Alberta, in this view, is its conservatism. And when Canada rejects conservatism, it rejects Alberta. And this conservatism can’t be disentangled from the oil industry.

Until relatively recently, the core impulse of alienated Albertans was to fix Canada, either by making it more responsive to western concerns (by establishing new political parties or suggesting institutional reform like a triple-E Senate) or by installing a Conservative government in Ottawa. We can think of this as the reformist impulse.

But the Firewall Letter marked the start of a different impulse: to retreat into Alberta as a conservative homeland. Written just after Jean Chrétien’s second re-election, it called for an Alberta pension plan, tax collection agency and provincial police force, as well as an assertion of provincial authority over healthcare and a provincial referendum to force Senate reform back onto the provincial agenda.

What was the goal of the firewall? To keep tax dollars in Alberta, so that “only our imagination will limit the prospects for extending the reform agenda that [the Klein] government undertook eight years ago. … lower taxes will unleash the energies of the private sector, [and] easing conditions for charter schools will help individual freedom and improve public education….”

After the re-election of the Trudeau government in 2019, Alberta alienation flared again. The Kenney government appointed the Fair Deal panel, which issued a report reprising the Firewall Letter recommendations, substituting a referendum on equalization for the referendum on Senate reform. A group of MPs penned the Buffalo Declaration, prominent Albertans (including Danielle Smith) took part in a conference hosted by Alberta Proud, focused on the question “Does Alberta have viable options and a credible case to go it alone if necessary?” and two lawyers and a political theorist got together to write the Free Alberta Strategy, with a proposed Alberta Sovereignty Act as its centrepiece.

To understand the impulse to retreat, it’s important to remember that most Albertans—including the Firewall authors—don’t really want to retreat from Canada. They’re frustrated reformers: they want to fix Canada, but Canada keeps resisting. And so, the policy suggestions they make stay within the constitution and probably hurt Alberta more than they hurt the rest of Canada. (If Alberta pulls out of the Canada pension plan, or replaces the RCMP, would the rest of Canada notice or care?)

The Free Alberta Strategy (FAS) ups the ante. And the difference is that the FAS authors might not be nearly as committed to remaining in Canada as the Firewall Letter writers were. I don’t know where the two lawyers—Rob Anderson and Derek From—stand on the question of Alberta’s separation. But the political theorist—Barry Cooper—is pretty clear in his views. Writing for the American Law and Liberty website, he says, “The position of the American Patriots in the Thirteen Colonies in 1776 is the position of many Alberta Patriots today.”

The justification for the FAS is familiar, if articulated in a new way. Alberta has been “economically terrorized” by the government of Canada, through, first, the equalization system and other transfers, and second, the deliberate strategy to phase out oil and gas. It goes on to argue that provinces are “voluntary” members of Confederation, “predicated upon the federal government abiding by its constitutional commitments to its members.” [Some constitutional scholars may disagree with this interpretation…]. The federal government, the strategy claims, has “relentlessly intruded” on provincial jurisdiction. And how has it done this? “They have used their own appointed and controlled federal courts to give these intrusions legal legitimacy.” So, never mind rule of law, because the courts are compromised.

The Sovereignty Act, as it’s described in the strategy document “would provide Alberta’s Legislature with the authority to refuse enforcement of any specific Act of Parliament or federal court ruling that Alberta’s elected body deemed to be a federal intrusion into an area of provincial jurisdiction, or unfairly prejudicial to the interests of Albertans.” The document goes deep into the need for a provincial police force that could be directed to not enforce offending federal legislation, a banking act that would try to push Albertans into provincially regulated financial institutions to avoid enforcement of orders through the federal Bank Act, and a tax collection agency that would collect Albertans’ federal taxes owing but not send them on to Ottawa. In other words, the full strategy would ensure that all Albertans were in violation of federal laws, but under the protection of the provincial government.

The concluding paragraph claims that “in the end, the federal government will have to negotiate if they want to resolve the situation”—in other words, this would be a hostage-taking, and we’re all sitting on the floor of the bank with our wrists tied together.

To be perfectly clear, what Smith is proposing does not endorse this whole scheme. The version she offered on her campaign website was this: “to refuse provincial enforcement of specific federal laws or policies that violate the jurisdictional rights of Alberta under sections 92–95 of the Constitution or that breaches the Charter rights of Albertans.” Since Smith was elected party leader, the proposal has morphed again, this time to respect the rule of law and Supreme Court decisions.

How should we situate the Sovereignty Act proposal in the narrative of Alberta alienation? Clearly, it is less reformist than it is retreatist. It comes short of pulling Alberta out of confederation but imagines Alberta enjoying some kind of Confederation Lite: only as much part of Canada as it feels like.

But we have to recall that underlying all the retreatist proposals is a reformist idea: if only the rest of Canada takes Alberta’s alienation seriously, Canada will reform itself, and things will be better.

The proposal is entirely consistent with the idea of Alberta as a conservative homeland. The fall announcement that Alberta would try to avoid having the federal firearms buyback program enforced in the province was a perfect illustration, trying to set the province up as a haven for those who value “property rights” over public safety.

Like last fall’s equalization referendum, it falls into the category of what I’ve called fantasy federalism, proposals informed by wishful thinking rather than sound constitutional analysis, designed to excite conservative supporters, but with no realistic chance of achieving their intended objectives.

Where the Sovereignty Act as proposed by Smith during the campaign diverges from the other proposals is in its blatant unconstitutionality. The Firewall Letter writers were careful to colour inside the constitutional lines. The equalization referendum was fantasy, but it didn’t try to give the legislature the power to overrule courts. The Sovereignty Act, as Barry Cooper pointed out in an op-ed in the National Post, is unconstitutional on purpose.

There are two reasons we have seen this escalation from constitutional to unconstitutional proposal. The first is that, as some observers predicted, the equalization referendum and other “stand up to Ottawa” activities of the Kenney government promised a lot and delivered little. As you might expect, this was frustrating for Albertans alienated from the federal government. The Sovereignty Act promises to up the ante by taking actions the federal government can’t ignore.

We are in a new, and frankly terrifying, era. People are free to find the facts they want and act on them.

The second reason is that we are in a new, and frankly terrifying, era. People are free to find the facts they want and act on them. In my reality, the Accountability Act is unconstitutional and COVID-19 vaccines are effective. In Danielle Smith’s reality, the Accountability Act is perfectly constitutional and COVID-19 vaccines are largely unnecessary except for the elderly. Trust in mainstream media, experts and institutions is in freefall, particularly among those who have fallen prey to misinformation and disinformation. Norms are passé. The sovereign citizen movement—folks who think that laws just don’t apply to them—is in ascendance, and active in the Freedom Convoy.

At this point it’s tempting to catastrophize. On one hand, I take some comfort in the moderating effect of parliamentary government. On her first day as premier, Smith signalled that her Sovereignty Act would not violate the rule of law. This is a compromise she had to strike to hold her caucus together.

On the other hand, once you have violated a norm, or even publicly contemplated violating a norm, the window of “what is acceptable” shifts. We need only look south of the border to see how quickly norms erode and place democracy in danger. The top takeaway from the Trump years is that the rule of law is essential to democracy. And so, any deliberate effort to erode it is highly problematic.

Lisa Young is a professor in the department of political science at the University of Calgary. This article was originally published at The Conversation, Oct 6, 2022 (Part 1) and at What Now?!? An Alberta Politics Newsletter, Oct 3, 2022 (Part 2).

____________________________________________