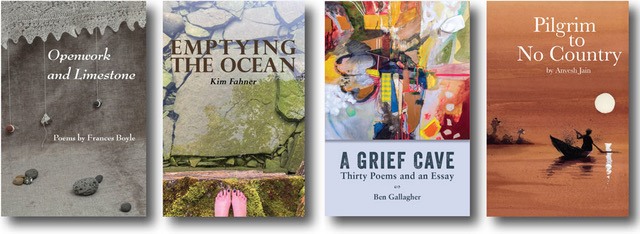

Openwork and Limestone, by Frances Boyle

Emptying the Ocean, by Kim Fahner

A Grief Cave, by Ben Gallagher

Pilgrim to No Country, by Anvesh Jain

FRONTENAC HOUSE

2022/$19.95 EACH

In late fall, as leaves and temperatures drop, new pages flutter from Frontenac House with their annual release, the Quartet poetry series. No obvious unifying content or style links the four new books in 2022, though each is a journey that leans in to territories actual, imagined, spiritual or emotional.

Ben Gallagher’s A Grief Cave: Thirty Poems and an Essay begins with tragedy, the death of a lover. Gallagher sets the context up front with a short, graphic paragraph ending with: “Around the corner I came to a line of police caution tape, and when I mentioned her name they drove me in a squad car to a nearby hospital.” The poems amplify. “I have a box / full of ash / invisible body / made real / I cannot give yet / to the wind,” read lines from “Looking for the Invisible.”

The writing, whether poetry or essay, is emotionally honest and stirs empathy—inventive in its approach to a difficult and language-defying experience. The poems are anchored in the concrete, while probing the otherworldliness of emotion and existence; they contain but move beyond the confessional I toward the mystical and occasionally the societal. The narrative is not merely linear. Memory haunts; in “The River”: “There was a time / we drank beer all the time / and the world felt // It felt light and burnt / a crème brûlée world / —your favourite—”.

Near the start of her collection Openwork and Limestone, Frances Boyle lays the threads that reach from family relations outward to the elements, the cosmos, with undertones of Gaelic and other mythologies, and to the poet’s existence in “fabled time.” Confession, biography and travelogue pull through the weave. Boyle, a time and space traveller, pauses with pen in many locales, occasionally with poetic sound play:

“Synchronous rush-slush, a wave of weeds,

a crash that isn’t heard but rumpatumps

through water”

Yet Boyle often falls back to straight-ahead, distancing, biographical reportage: “I am wounded, but why did my belly clench, fist-tight, when I read / that scene in a Toni Morrison novel”. Many poems are photographic, aiming to capture nature, as in “Strand”: “Between water and dune-edge / —hardscrabble salal, / spiny-tough grass tufts, / driftwood in tangles.” Such description is simultaneously specific and vague—vivid in the poet’s “I-eye,” but raising the question of how to make the seen rich for the reader and relevant beyond the poet’s moment. Representation salted with hope seems to be Boyle’s intention—the hope that scenes and their generated contemplations will ignite in a reader’s mind. Sometimes they do, as in the vivid, verb-based description: “Sheets billow and fill, / brush my face, wrap hips, shins. / Their touch is shivery.”

Kim Fahner, in Emptying the Ocean invites the reader to join her poetic voyage guided by tidal pull, cycle and myth. She begins on the sea, with its elements and creatures, in a suite of tiny songs, where the language surges, lush and evocative:

“the ice yearns

and longs, moans, shifts in sleep, rolls restless.”

Crafted sonority pulls us through the waters of Lake Erie, Newfoundland, Connemara. Fahner moves us onto land, its flora, its seeds and trees, minerals and tailings. Attention shifts to “Fire,” then to “Air,” where bees, dragonflies, moths and butterflies flitter, and all the lost birds spur an environmental lament. Fahner visits the creative spirit of womankind—Medusa, Persephone, Maude Lewis, and notably with the nine-part homage to painter Mary Pratt: “Solitude, sharp necessity for the image-summoning. / Pain like the red of pomegranate juice, spilled, / clotted. Jewelled fruit that sparkles, brilliant bright.” Through all, Fahner does not lean on the I. She shifts person and foregrounds ideas with vivid turns, making poetic moments direct and alive.

In “Coming,” the last poem of Pilgrim to No Country, Anvesh Jain writes: “Someday I was going / To write diaspora poetry, / Pen the great ironies of my displaced kind.”

I suggest he has reached well toward this intention with this exploration of emigration and immigration, its challenges and inspirations. He captures that experience, not linearly but as assemblage, with juxtapositions that corral how multiplicities of identity, history and lived reality co-exist in dis-placement and re-placement. He combines biography and imagination in poetically adventurous, jittery language, for example blending Indian terms and deity names with familiar English, as in “Ramayana Western: A Quarantine Epic”: “Only a Cowboy could find Sita / And BTW, O Laxmana, where art thou?”

His lines judder with the unexpected. While the work is serious, there is wit, even humour, for example, as the speaker practises a cricket swing in his Calgary backyard: “Tock! (proper / footwork) Tock! / Tock! (properly) / Between calypsos, the radio goads / Go west, young man, / To Canola Country, Boomtown, / Oilseed Prairiestan, tar sand / Petrostate. Cry me a Bow River, / … / There’s no better place for a Hindoo / Than Cowtown. / Tock! / Tock!”

The poet aches to align his birthright and birthplace with his new-place. He writes, metaphorically, in “Minar”: “You, concrete, pour / And pour and pour / Into me. Make full / These historic gaps, somehow.” This is a wide-ranging and engaging work—a notable contribution to current diasporic texts.

Steven Ross Smith was Banff Poet Laureate, 2018–21.

_______________________________________