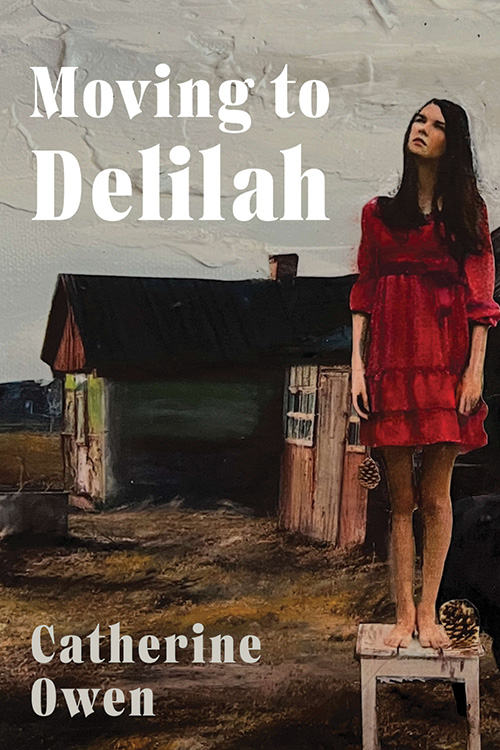

Catherine Owen’s Moving to Delilah opens with a news story encouraging young people to leave “lands where/ the old and rich hoard the ocean or the lakes.” For the speaker of these poems, priced out of the coastal “salt & cedar” of her heart, Alberta emerges as destination and site of life-altering history.

Early on, the poem “Returning to Edmonton, nine years after” informs readers of a sudden loss on Jasper Avenue. This loss, and the reflective present handling of how it has shaped the poet’s life, underpins the book’s lyric examination of home, with Owen sifting through layers of memory via the more than century-old prairie home she purchased: “As if living on for a ghost some days…/ Why did I move back./ Homage, not squander, I guess./ Putting what he left me into a thing of future.”

The house is called Delilah, its age and experience earning the name. Unfolding in four sections, from Prologues through The House, The Garden, and The Neighbourhood, the book’s investigations into the history of Delilah’s construction and inhabitants gird more intimate musings with sturdy structure, as do a range of poetic forms including sestina, haiku, pantoum, haibun and sonnet. Details, such as that of the photographs found in a wallet in the roof of the garage, highlight the lingering traces of lives lived around us, as well as grief’s sweeter mysteries and ongoing nature. “When you look around you feel at home, allowed, contained,” and yet “winter is a place you will relearn every year.” Metaphors of containment and integration abound as the homeowner settles into a place of their own on adopted topography. The garden’s many relationships show the thrills and challenges of bonding with a place and sowing seeds. Botanical observations are relatable and frank: “an allegiance to peonies” cultivates an “anticlimax of carrots.” Crabapples thunk to the ground as bittersweet musings turn up in the “puttering made possible in dirt you pretend you own.”

Memories of the lost and past are bound up with the house. The ghost in the wood grain can be addressed, which is a comfort, though the poems know that “this is a house,/ not a resurrection-machine.” Pragmatism pushes on—“at least you can’t die again” the poem called “Delilah” says.

The Neighbourhood expands, moving from Strathcona postcards circa 1905 to Edmonton haunts like the Wee Book Inn and road trips around the province in the 2020s. Between first snows and the edges of melt, we find “adoring the ice is equally/ as possible as the salt.” Sometimes we “carry two buckets” of places within us, as “home accrues” and we turn pages “to the fissures where nests begin.”

K.B. Thors is an author and translator from Red Deer County.

______________________________________