On the first Saturday of summer 2024, the Alberta New Democratic Party unveiled the results of its leadership vote in a Hyatt Regency Hotel ballroom in downtown Calgary. I arrived about an hour before party members began to assemble for the announcement, with less doubt about the outcome than that of any democratic process I’d ever participated in—but only a loose sense of the size of the victory.

Consider this also my disclosure that I’m a party member—reluctantly—and a confession that I’ve spent much of the past 20 years needing to hope, usually against all evidence, that the results of a democratic vote in Alberta might pleasantly surprise me. They’ve done so on a few rare and exquisite occasions, the two most notable ones involving both the party gathering that day and its frontrunner candidate—though not both at the same time.

I’d watched in delighted shock as Naheed Nenshi won his first mayoral race in Calgary in October 2010. I’d stood with thousands of others in front of the Legislature in Edmonton in May 2015 with my jaw agape to Looney-Tunes-character levels, still unable to fully process that I was watching Alberta’s NDP being sworn in as the new government. (I wasn’t a party member then and I still don’t like being one, but for now I’m reluctantly in the wing of the party that is genuinely bothered that my Alberta NDP membership also means I’m nominally a federal NDP member.) And now I’d arrived at the Hyatt Regency’s Imperial Ballroom to witness Nenshi being chosen as the NDP’s new leader. A few months earlier this outcome might’ve shocked me nearly as much as that first mayoral victory. Nenshi was very much not a partisan of the NDP (or any other party). But the result was a certainty by the time it was made official.

The route by which we’d arrived at this moment is likely familiar to anyone paying even casual attention to Alberta politics, but here’s my condensed version: In 2023, as the culmination of a stunning political comeback, Danielle Smith led the United Conservative Party to re-election and retained her position as premier. She did so by winning virtually every non-urban seat in the province, along with just enough ridings in Calgary to seal the deal. Her margin of victory consisted of only a few thousand votes in close Calgary races, making electoral success in that city appear absolutely crucial for winning a provincial election from here on out. This is all uncharted territory for Alberta politics, because until 2023 there hadn’t been a genuinely close two-horse race here in living memory.

The slim margin of victory notwithstanding, Danielle Smith was premier again, and in her return to power she summarily commenced to do Danielle Smith sorts of things. These included, in just the first few months, upending the management and structure of the healthcare system, actively impeding the province’s wildly successful renewable energy business, and tossing aside a long-standing rhetorical commitment to LGBTQ+ rights to bring in new policies designed to make life worse and more dangerous for LGBTQ+ youth. This last Danielle Smith sort of thing may have been the final straw for Nenshi, who’d surely been hearing pleas to consider a run at the NDP leadership since the day he stepped down as mayor in 2021. He joined LGBTQ+ activists in February 2024, in front of the very City Hall he’d once presided over, to deliver a ferocious and powerful rebuttal to Smith’s new policies, which would change the rules around gender-affirming healthcare and oblige schools to notify parents of a child’s name change (and require parental consent for those under the age of 15). Effectively, it would soon be provincial policy that school administrators must out trans kids to their parents whether the kids were ready for that or not.

An NDP leadership race had never been like this one: the stakes had never been as high.

Nenshi’s speech at that rally left no doubt that he took Smith’s abandonment of her commitment to protect LGBTQ+ youth personally. He has known her since they were both active in campus politics at the University of Calgary in the early 1990s, and he claimed he’d taken her at her word that she wouldn’t do anything as premier to make the province less safe for those kids. This makes it highly plausible that whatever mix of factors convinced Nenshi to abandon his own long-standing commitment to non-partisanship, Smith’s new socially conservative policies regarding LGBTQ+ youth ranked high on the list. (I know Nenshi socially, but I’m not privy to any of his thinking on this decision.)

In any case, the former mayor declared his intention to seek the Alberta NDP leadership in March, five weeks after that City Hall rally. And his candidacy summarily changed the dynamics of the race with all the subtlety of a prairie hailstorm. Within weeks, the party’s membership numbers had risen to such a stunning degree that one of the candidates, Edmonton MLA Rakhi Pancholi, viewed as a strong contender for the leadership, ended her campaign and shifted her support to Nenshi.

There followed the usual mechanics of a party leadership race—stump speeches and town-hall meetings, social media ads and debates—but no objective observer expected any result other than the one that greeted us on that sunny June day.

So join me back at the Hyatt Regency. Ride up with me on the escalator from the lobby. Overhear a prominent Calgary Sun columnist a few steps farther up discussing his summer holiday plans. And soak in the obvious symbolism of Alberta’s NDP gathering in a luxury conference hotel’s Imperial Ballroom in the heart of corporate Calgary to welcome its new leader. Historically, the NDP is not corporate, nor luxurious, nor based in Calgary. And if you go far enough back—not that far, really, perhaps to 2014, when the NDP was fourth in the provincial seat count—that Sun columnist up ahead of me on the escalator surely didn’t feel obliged to cover their leadership events, because it didn’t matter much to Calgarians who the head of the provincial NDP happened to be.

Let’s skip ahead now past some friendly nods and how-ya-doins to the main event. The party faithful now gathered to fill the room, the small talk friendly and anxious, the number of faces I associate primarily with Nenshi’s municipal politics running roughly 1:1 with faces I associate primarily with Calgary’s fledgling NDP machine.

Greetings from the Grand Hyatt ballroom’s podium on this day fell to Joe Ceci, the former NDP finance minister and de facto head of the party’s Calgary caucus. Ceci opened with a short, vivid anecdote about how far the party had come. When he’d first mulled a run for a provincial seat in the months ahead of the 2015 election, he said, he’d given real consideration to running as an independent. Not even a decade ago, the NDP’s standing in Calgary had been so weak that it didn’t seem to offer him anything that a resourceful candidate with the organization and name-recognition of a former city councillor couldn’t cobble together for himself.

Even if he was overstating how seriously he’d considered the indie approach, who could’ve blamed him if he’d gone that way? Ceci was, after all, a Calgary progressive, and he knew as well as anyone in the room what that had meant before 2015. It meant there was no clear path to victory at the provincial or the federal level and never had been. So what did it matter which party banner you stood under? The goal for a Calgary progressive running in a provincial election was to try to steal a single seat in the Legislature, where your likely role in the real business of government would at best consist of trying to broker a deal or two with the reigning conservatives to get some pale facsimile of your ideals embedded in the legislation they were rubber-stamping. Provincial politics were dynastic in Alberta, and the dynasties were conservative. Serious opposition to the regime came almost exclusively from breakaway factions in its own ranks. But a progressive? Running in Calgary? Red, orange, purple—the colour of the banner barely mattered at all.

The dynastic nature of Alberta politics isn’t news, I realize. But the full scale of it is worth pausing to marvel at. From 1935, when William Aberhart’s Social Credit party defeated the United Farmers of Alberta to form government, until 2015, when conservatives spread their votes evenly enough across two parties to hand the Legislature to the NDP, there had been one change in governing party. Of the nine Social Credit governments, only two controlled less than two-thirds of the province’s seats. The Progressive Conservatives formed 12 governments, and only two of those—the one that brought them to power in 1971 and the Liberals’ near-miss in 1993—were majorities of less than two-thirds. Tally it up: 21 governments, one change in ruling party, and essentially no serious challenge to conservative rule other than that interregnum between the Lougheed and Klein dynasties, when King Ralph was left to eke out his first win in 1993. To be a progressive in this 80-year epoch was to make some sort of peace either with occupying the thin progressive section of the conservative benches or residing forever in the wilderness of no-hope opposition, alongside a dozen or so other lonely souls.

All of that changed with the NDP’s shocking victory in 2015—possibly forever. And everything since, including Joe Ceci’s fun little warmup joke about seeing more hope in flying solo than in riding with the party that won the whole election, has been an exercise, by turns giddy and gut-churning, in trying to map out the new landscape on the fly and find the strongest footing in this wild new terrain.

In 2024 winning the leadership of the NDP meant, for the first time ever, taking the reins of a progressive party with a legitimate shot at forming the next government. There had never been an NDP leadership race like this one, because the stakes had never been as high. There’d barely even been stakes before.

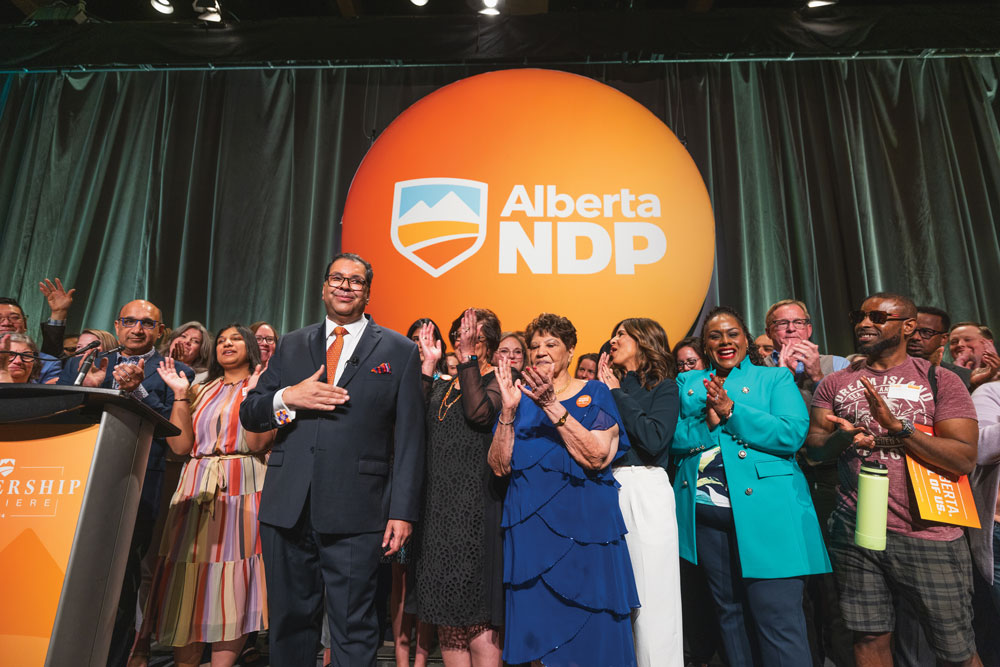

June 22, 2024. Nenshi got 86 per cent of the vote. In his victory speech he shared his vision of an Alberta ready to “start dreaming big.”

So that was the NDP’s path to this moment. What about mine? I was looking on from the sidelines at the Hyatt Regency that day, knowing—before his name was called—that I’d registered my vote for the victor. And, yes, wishing I hadn’t been obliged to also become a member of the federal NDP in order to do so.

I take party affiliations seriously. It matters less to my kind of journalism than it does to a daily reporter on the government beat, but I don’t ever want anyone to assume I’m speaking for anyone but myself. I’ve only been a party member at any level twice before. The first time was a federal NDP membership, which I bought to lend my support to Jack Layton’s run for the leadership in 2003 because he was the first politician I’d ever heard talk sensibly and at the appropriate scale about the climate crisis. I let that membership lapse when Layton’s NDP cynically attacked good climate policy to hasten the destruction of the Liberals under Stéphane Dion and his “Green Shift” platform in the 2008 election. The federal NDP has still not restored real coherence to its climate policies—which is, in part, why I resented being made to join the party as a necessary condition of my Alberta NDP membership.

From a base of 16,277, the party grew to 85,277 members eligible to vote for the new leader.

The next membership I took out was with the Green Party of Canada, so I could run as (and vote for myself as) the Green candidate in the 2012 Calgary-Centre by-election. I let that one lapse when the Liberals arrived with a workable and effective climate policy package in 2015. I was a member of no party when Nenshi declared his candidacy for the Alberta NDP. One of his stated goals on the campaign trail was to consider whether the party should maintain its formal partnership with the federal party. It’s not a trivial question, and it cuts to the core of what kind of party the Alberta NDP is and wants to become.

Back at the Hyatt’s Imperial Ballroom, Joe Ceci ceded the podium to a series of officials variously touting the party’s bedrock social democratic values and celebrating the fact of its extraordinary growth during the leadership campaign. The numbers were legitimately impressive—from a base of 16,277 at the start of the race, the party had grown to 85,277 members now eligible to vote for the new leader. The surge in membership was widely acknowledged to have been a product of the attention that accompanied Nenshi’s candidacy—particularly in Calgary. And it is likely in Calgary where the question of the Alberta NDP’s federal ties is most urgent.

When Nenshi raised the issue during the campaign, Rachel Notley responded with a full-throated defence of the formal federal link that provides a particularly clear illustration of the limits to the party’s growth—in appeal, perhaps also in imagination—under an old-school NDP leader. In an interview with the Calgary Herald, Notley responded to Nenshi’s challenge by pointing out that she first met Tommy Douglas when she was just four years old, which is about as strong as bragging rights get in NDP circles. “The idea of running away from that brand is to me silly, superficial, short-sighted,” she said.

When I ran for Parliament in Calgary in 2012, I quickly learned that long-time campaign volunteers share a lore about the parties. Conservatives tend to run the most aggressive campaigns, Liberals the most arrogant ones. But no party, so goes the lore, is as fiercely partisan as the NDP. NDP campaigns have a reputation for trusting in fellow Dippers from afar over local experts lacking sufficient party ties. The NDP would rather maintain righteous internal agreement on a key issue than massage a position to win a race. They too often prefer the correct stance over the best tactics. And that perhaps explains, at least in part, why Notley’s NDP, facing an uphill battle to unseat an unpopular UCP government in 2023, came to the conclusion that unveiling plans for a corporate tax hike was a move worth making in the middle of a struggle to win over Calgary voters wary of a party considered hostile to business.

I can’t say exactly how Notley and her team arrived at that particular decision, and I can’t say with certainty that it was a pivotal factor in the NDP falling a few thousand votes short of victory in a handful of Calgary ridings that would’ve delivered enough seats to win the election. But I do know that political insiders familiar with the lore thought it was exactly on brand. Maddeningly on brand. Which is why changing the brand does in fact matter—because it’s not just the brand that changes under a leader with no previous party affiliations but the whole way the party thinks. And to consistently compete for and win elections in Alberta, the NDP needs to learn how to think differently from its old-school roots. It shouldn’t feel in any way like it is abandoning those roots—the party’s long history of championing workers’ rights and building social democracy are assets in Calgary as much as they are to its long-standing Edmonton supporters. But it must become a party with a broader and more nimble imagination, a party that can attract votes from Lougheed Tories and traditional Liberals recently arrived from the rest of Canada as readily as from its union-backed “Redmonton” base.

I attended a leadership debate at the BMO Centre in Calgary in mid-May, and Kathleen Ganley summed up the NDP’s experience in the 2023 election this way: “We were right about everything. But it wasn’t enough.” The candidates on stage—Sarah Hoffman, Gil McGowan and Jodi Calahoo Stonehouse, in addition to Ganley and Nenshi—spent a good portion of the debate praising each other, tacitly agreeing with Ganley’s assertion that the party was on the right side of the issues. All also agreed, though, that the NDP had to expand its appeal beyond its traditional base. Being right was not enough—the party needed to learn how to win in the two-horse races to come.

Vigorous agreement doesn’t produce many sparks, but Hoffman and Nenshi did engage in a heated exchange over the City of Calgary’s closure of a mobile home park under his mayoral watch. Nenshi defended his record vigorously, and the discussion spun off into policy esoterica. I happened to look over just then and notice that Zain Velji, the Nenshi campaign’s co-director, was seated just across from me in an empty row at the back of the room. His gaze never left his phone throughout, nor showed the slightest concern at the sharp attack his candidate was fending off. I’ve known Velji since he chipped in on my campaign in 2012, and I know first-hand that he understands the lore as well as anyone. He didn’t seem at all worried—and didn’t need to be—that Nenshi’s social-democratic bona fides were being called into question. The tens of thousands of new members registering to vote in the leadership race were not rushing in to argue over shades of orange in an urban housing policy. They were coming because they reckoned the party’s tent might finally be broad enough for them, and because the ringleader they were coming to vote for might attract a crowd big enough to win the next election.

I was surprised by the results after all. Not by the outcome—Naheed Nenshi won easily—but by the sheer size of the victory. I’m not an NDP loyalist, not aware of its internal dynamics. I’d heard rumblings about an old guard that might rally a bit against the insurgent and assumed there was some truth behind those rumours. Instead, the announcement of the vote tally, when it came, echoed around the Imperial Ballroom to affirm a coronation. Nenshi received 86 per cent of the vote. The nearest runner-up (Ganley) came in at only 8 per cent. I wasn’t expecting multiple runoff tallies or anything, but I didn’t anticipate such a landslide.

Elation filled the room. No surprise there—everyone on the winning side in politics seems at least a little delirious about it all, regardless of the stakes. What struck me the most was the sort of tableau the elation created. In his victory speech, Nenshi contrasted his vision of an Alberta ready to “start dreaming big” against the small-minded, defensive, backward-looking UCP version. He described his province not as a “fortress to be defended” but as a “wide-open door with a welcome mat.” And then, one by one, he called up the members of the NDP caucus to attest bodily to that vision.

Here was an NDP caucus showing legitimate, lived-in diversity with effortless ease. Here was an NDP caucus numerous enough to fill the Hyatt Regency’s stage to overflowing—something few progressive caucuses in the province’s history could accomplish. Here, more than that, was an NDP caucus that looked and felt like the Alberta I’ve known and loved best in my 20 years as a resident and sometime dreamer of brighter political futures, a place that truly is remarkable in its open-mindedness and progressive ambition. If that isn’t the only Alberta there is, it’s the one that has been most notably absent as a permanent presence in its politics for most of the dynastic conservative epoch.

Here was a real, united, ambitious opposition, ready and able to contend for power not just in the next election but in any number after that. Never has that existed in Alberta’s progressive politics. And that’s why I’m willing to hope, to dream—to bet, even—that an entire new epoch began on that first Saturday of summer in downtown Calgary.

Calgary’s Chris Turner is the author most recently of How to Be a Climate Optimist, which won the 2023 Shaughnessy Cohen Prize for Political Writing.

____________________________________________