I sit in my tent on a hot August day, pencil not quite in hand but close, like a gun in a holster, and I wait. Waiting is a discipline unto itself, and I’d wager I’m one of the best at it of anyone I’ve met. I’m waiting for a customer to arrive, or at least a curious fair-goer, who can be transformed into a customer four times out of five. The fifth ones are too much like hard work, and not worth the wait.

I’m at the Lethbridge Fair, which is much like the Regina Fair and the Brandon Fair and the dozens of other little fairs I’ve worked since leaving the maritimes over a year ago. This is my pilgrimage westward, and Alberta is the penultimate stop before I see the ocean again. The big P, as folks call it out here. Coming from the big A, I figure it’s an admirable advancement. most travel only from A to B but not Tara hale… she made her way more than halfway up the alphabet in 15 months flat.

So far today I’ve sketched two little girls, twins, their faces red and luminescent with sugary stickiness from a candy apple gorge. The mother spent the entire session justifying the expense to the father, who never once uncrossed his arms and only exhaled with audible judgment at my work as he stood directly behind me. This is something I don’t normally allow, but it was already half past 12 and I hadn’t had so much as a visitor in the tent, so I kept my mouth shut and sketched.

Justify the expense. Hardly. My drawings are four bits each and I found myself negotiating with the silent husband by way of the vociferous wife to arrive at a total of 75¢ for this one. I would normally charge per subject, but she argued that I was only out one sheet of heavy cardstock paper rather than two, so that ought to count for something. I eased my rage at this nitpickiness by imagining the two of them embraced in the heat of their Friday night agreement, her white string- bean body submitting to his meat ’n’ potato thrusts with the same rationale: if I can produce two in your image for the discomfort of one night of violation, then that ought to count for something.

Despite my vindictive intentions, these daydreams instilled a sense of compassion for her, and I relented on the price. Besides, I need whatever I can manage for train fare to Calgary, a hundred miles north of here. Another in a series of trading-fort towns, but this one hosts the first-ever Stampede next month, which, by all accounts, will be the pot-of-gold of summer fairs. If it’s half as lucrative as Weadick keeps predicting—even by 1912 standards—then there will be train fare all the way to Vancouver with enough let over for a couple nights in the Rocky resort of Banff. I need this to rest, read and romp—with a little luck—with a man of distinction, ideally from Europe, who preferably speaks no English. These trysts come off much better if conversation is removed as a fallback.

After the twins, a spinster came with her dog and made my day, getting three sketches done at once: herself, her dog, and the two of them together. She said she had a collection of sketches from across the world, but these, she confessed, were her first caricatures. I asked if she was interested in a proper portrait, with oils and canvas (the payment for which would surpass even the wildest of Stampede successes), but she could not afford it. She said “could not,” but I only heard “would not.” I imagine the cost would be a fraction of what she likely spends on her pet, but there’s no accounting for taste and priorities in this world.

I’ve eaten my lunch, consisting of a hard-boiled egg, half an orange, and a stale corn biscuit without butter. Two more sittings and I can close up shop for the day and make the 4 o’clock train.

I turn my face northward with thoughts of Calgary, and feel my heartbeat quicken, the sudden rush of blood causing me to catch my breath. It’s the thought of being so far from home with nothing tying me back there aside from memories and a continued desire to stay away.

—You know if you go far enough and take long enough to do it, you’ll only end up right next door to us, Tara.

—O, come on, dad, that’s just wordplay. He laughed when I said this then wrapped me up in a hug as if my hair was on fire.

—My little girl. have I been so terrible a father that you feel the need to go so bloody far away?

—I’m 25 years old, and Vancouver isn’t that far away. It’s still Canada, just like here.

—Tara, a person can so adjust his thinking that he can be in the same room, within arm’s reach, and still be on an entirely different planet. distance is only what we make it, and space is something we can kill just as easily as we kill time. don’t believe everything you hear: Vancouver is right next door for some; for others it’s an impossible destination.

—You like to hear yourself say these things, don’t you? Like you’re Mark Twain or something.

Again he laughed. I was the only one who could ever successfully call him on his linguistic indulgences… a student of his tried once and was immediately and systematically dragged over the coals in the lecture hall by my father. I felt sorry for him, but, damn it, my father is good with language. The way I want to be with colours.

It was when I told him this, explaining my aesthetic reasons for leaving, that he finally understood. his protests became warm smiles, and he quickly silenced the rest of the family on the matter. When I boarded the train with my rucksack and case of paints, he handed me a thin volume of Emily Dickinson poetry and a bottle of French wine from his collection in the cellar.

—You’ll finish one long before the other, he said, but they’re both for the long train ride ahead.

I haven’t heard from him since, never staying in one place long enough to justify a return address. I send letters home frequently, though they invariably take the form of a sketch with an accompanying quote from the Dickinson volume, one that comes closest to expressing my mood. Thank God she was such a melancholic.

Did you draw all these?

I was shaken out of my northward stare and nostalgia by a young man standing in the tent looking at the display of pictures I had hanging on the canvas walls.

—Every last one of them, I answered.

—Hmm.

His hands were pushed so deeply in his trouser pockets that the force would have pulled his pants right down if not for the salvation of the leather suspenders.

—This one too? he lifted his chin to a picture I had drawn late one night in Manitoba last April after reading the paper.

—That one too.

—Who is she?

—The maid of Mr. and Mrs. Allison. She died on the Titanic.

—You knew her?

—No. Hers was the first anonymous name published in the paper after the sinking. I felt she deserved a bit more than the dismissive “maid” she was immortalized as.

He took in the drawing for some time, masking the clear fact that he knew nothing about the name “Titanic” or the catastrophe that had occurred four months earlier off the coast of my home province.

—What’s the matter with her eyes?

—How do you mean?

—Well look at them… they’re about twice the size of her entire face and bigger than her legs. Was she some kind of freak or something?

—If anyone is to be called a freak, I said, I claim the title as my own. I have no idea what she looked like, but I imagine her countenance was as normal as anyone’s I draw. I’m a caricaturist.

—A what?

—Caricatures. Don’t look so amazed; it’s a popular form of sketch art at fairs like this. Well… not like this one specifically. Others. Elsewhere.

—Never heard such a word before. He rubbed his chin with the back of his hand. What’s it mean, you figger?

I moved the stool out into the open, hoping he would take a seat. If you can get them sitting, then the deal is as good as done.

—Well, I said, setting a crisp white card on the easel, “caricature” comes from the French, like all great art—meaning “to overdo.” I imagine it’s originally from Latin.

—You imagine? he said this as he sat down, the smile indicating that he caught me out in a feign of ignorance… a ploy I’m often guilty of to make people feel at ease.

—You’re right, I don’t imagine… I know it comes from the Latin. It’s from the root word for “carriage.” To load up too much, to overload. hence the big eyes on the freak.

—My father’s a churchman, he said. he knows enough of Latin to “untangle the mess that was made of our Lord’s message,” quote unquote, and thought it necessary to teach me what he knows, but he could never make it stick with me.

—Well, I said, now you know something.

—Your father a churchman too?

—Hardly. He teaches English at a university in the maritimes. American poets, authors, men of letters. Melville, Hawthorne, Whitman. You know.

—So he taught you Latin?

—He got me started, I suppose, but I learn most of what I know through reading.

He laughed slightly and said, my father claims that to give a woman a book is to give a fox the keys to the henhouse.

—You ever consider the fact that your father’s an idiot and an ass?

This came out before my little censor could block it. Damn it. I could lose this customer and I can’t afford to lose anything right now. Just keep your mouth shut, Tara, and your hands open if you want to get to where you’re going. But he laughed with his belly until tears came to his eyes, which he wiped with a handkerchief from his pocket. he threw it down on the ground afterwards like a flag, as if to signal the beginning of a race.

—Considered it a thousand times but never had the nerve to dress such thoughts up in words, he confessed through his laughter. This way I get to hear them said without suffering the guilt of saying them myself.

I started in with the drawing.

—Ain’t never had a picture made of me before. How much does it cost?

—Fifty cents.

He moved his lower jaw out in a frozen moment of consideration.

—Fair enough, he said. How long you figger it’s going to take?

—Well if you quit asking questions and keep your mouth closed, I’ll have you out of here in fifteen minutes or less.

He stood up as if I’d just shot at him with an aim to blow his balls clear off.

—Are you for real? Four bits for just 15 minutes work? That makes… what… two dollars an hour. What I wouldn’t give to be earning them kind of wages.

It was the word ‘wages’ that struck me. I never once considered myself a ‘wage earner’. Maybe it was because my father earned a salary, or at worst a stipend, that the word ‘wages’ connoted for me the sense of someone doing a deed which they took no interest in. A loveless exercise, like whoever the hell it was rolling that boulder up the hill in perpetuity. Wages were something the “haves” paid out to the “have-nots” for services rendered, not something you were compensated for in your calling.

—What would you do with a two-dollar-an-hour wage, mister…

—Snow.

—Mr.Snow.

—Oh please, he said, don’t call me Mr. Snow. That’s my father and believe me, you wouldn’t mistake me for my father once you met him any more than you’d mistake a ground squirrel for a grizzly bear.

—Glad to have you in my studio. Please… make yourself comfortable.

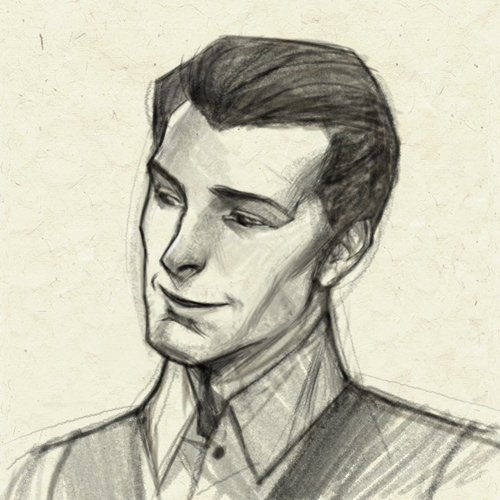

He turned around, looked over his shoulder, turned back and shrugged, then sat down on the stool once again. I re moved his hat for him. His blond hair fell down like straw and covered the tops of his eyes. I brushed it away. I came back to the easel and took my first long look at my subject.

He was stunning. His body was that of a child… all limbs, muscles, and joints in harmonic proportion… as though age had not interfered with the perfection of youth in this man. His face… I had never before seen a face like it, and I’ve stared at many. If I called it an animal face one might misunderstand me, but that is what it was. A thoroughbred animal face, like a fine horse or dog: a blend of man and beast, more beautiful than either.

I don’t believe in love at first sight. I don’t. I like to think that something as mighty as love takes a little more time to gestate. It wasn’t about that, not at all, it was just… he was like the sky in these parts: something inside of you can’t help but stop and look and be in awe.

—You were saying about the wages…

—Sugar beet molasses, he said.

—Never heard of it.

He slapped his hands together, the noise of which could have been herald to a thunderstorm, and rubbed his palms as though trying to start a fire.

—If you were a man, wouldn’t you enjoy a glass of rum now and then?

—If I were a man, no doubt I would. I’d even enjoy it if I were not a man. Which I’m not, in case you hadn’t noticed.

—Right, he said, his eyes flickering to my bosom and then back to my face without the hint of a blush. Sorry. You indulge then?

—It’s been known to happen.

—Normally I’m just talking to men about this. Other than my father. Never said it to a lady before.

—Rest easy, then. I’m no lady, just a growed up girl. But for the record, I’m more of a wine and whisky drinker. Rum’s too sweet.

—That’s the molasses talking.

His eyes darted off to double-check some imaginary scroll of his rum pitch, then came back to me.

—Rum makes the world a better place for some, he said, continuing his barker routine, but it’s got to come from somewhere. Ask me “why not here?”

—Okay, I said, I’ll bite. Why not here?

He was twisting on the stool like a barroom piano player working the crowd.

—Christian temperance, despite the dancing girls and brothels in towns like this. Whoring and rum consumption are viewed with at least one blind eye, but rum production would never escape the full-on glare of powerful churchmen like my father. A fella would be a fool to dare open a distillery round here.

—Something tells me that you’re no fool.

—No ma’am, he laughed. His laughter was free of knives, a child’s laugh, the sort that’s as infectious as a yawn and just as involuntary. I found myself genuinely caught by it and sharing in it… something I don’t normally indulge in except with my father.

—So where’s your rum empire going to be?

—’Bout 20 miles south of here. Next door to the sugar beet factory.

That’s when it flashed in his eyes, like lightning, and I felt the electrical charge shoot through me.

In order to bring off the desired illusion, an artist has only two things to work with: light and colour. Outside of the illusion of art, light comes from the sun. Or fire. Or kerosene lamps. Or electricity, in places as advanced as Lethbridge. A source of light must be imagined to exist in the illusion. Light hits the subject from somewhere, otherwise how could it be seen? And of course, with light comes the problem of shadow. When light hits the subject a shadow is created… very tricky to show in the illusion. The hallmark of the amateur is to leave shadow out completely. But then the illusion is only half real, and therefore not real at all.

I eased my rage by imagining the two of them embraced in the heat of their Friday night agreement.

As for colours, the caricature artist uses only one: black. A single pencil made of charcoal… the remains of something that once had colour and ever too much light. Charcoal is the colour of shadow, but still I make it reflect the light. It’s how I justify the expense.

—Are you finished yet? —Almost. Keep still now.

When a light shines on the outside of someone, that’s what you sketch. When it shines on the inside, you can only portray. The light was shining on the inside of this Latin-spouting preacher’s son and I was caught in the fire that burned from his eyes. I may not believe in love at first sight, but I believe steadfastly that inspiration happens this way. I knew then that I had to paint his portrait.

—Done. I stepped back from the easel and he relaxed his pose.

—Well let’s have a look, he said as he put his hat back on and stood up from the stool.

—Could you come by tomorrow, I asked, and the next few days after that? I want to paint you.

—Paint me?

—Your portrait. With oils, on a real canvas.

—Takes more than fifteen minutes for that, hey? —Considerably.

He stood staring at his sketch, but I could tell his mind was mulling over my offer.

—I wouldn’t charge you anything for the painting, of course.

It would be “on the house,” as they say in the tavern. —Wouldn’t know. Never been inside a tavern before. He laughed again. Naw, I gotta get home.

—Where’s that?

—Little village west of here. Emmett.

He searched my face to see if I had heard of it, then said something to the effect that no one ever has. Too small and insignificant to register with anyone not from there, and even the residents forget about it when away.

—Not much of an exaggerated carriage here, he said, lazily pointing a finger at the finished image on the easel.

—It’s only a sketch, I explained, a study for a larger work, I hope. I couldn’t caricature you even if I wanted to.

—Why not?

I detected a small measure of defence in his voice, as if he felt inadequate somehow.

—I don’t know… maybe you’re too beautiful for that. There was just no way to ridicule your face… kindly or otherwise.

His reaction—a mixture of laughing pleasure and blushing awkwardness—told me that no one had ever said these words to him before. Personal beauty must not have been a consideration for a man in his family. I understood then that his easy laughter was a way of lubricating his person into a calloused, male world of hard work, hard prayer and simplicity. otherwise he wouldn’t fit, and when you don’t fit into those tight little worlds, the results are often unspeakable.

—Thanks for the sketch, he said, but I really should get going.

—I’m Tara, I said, thrusting out my hand like it was spring- loaded, in an attempt to keep him there a little longer. Tara hale.

—William!

The voice came from behind him, at the entrance to my tent. A deep, resonant boom that hit the ground and shook the earth. here was the thunder that followed the lightning in my subject’s eyes.

—Hey, pop! He turned back and winked at me, as if to say “watch how I handle this” or “keep on your toes” or some such silent instruction.

—William. Where have you been? There are an awful lot of supplies needing to be loaded on the wagon before supper, he said, and I’ve been up and down the town looking for you since breakfast.

His father was not a tall man, but he made one feel in the company of a giant by his mere presence. His beard came down to his breast, wiry and curled like a mess of inappropriately positioned genital hair, and did its best to conceal a formal dress code of shirt, tie, vest and jacket done up to the utmost button, his collar white and starched and tightly wrapped around his sunburned neck.

—Just enjoying my day at the fair, pop. Got a picture made of me and everything.

—So you did.

The disapproval in his voice was evident, though he tried to hide it. I’ve heard the tone so many times that it’s impossible to hide from me. Still, he removed his hat and stepped forward with all the decorum one would expect.

—I’m Charles Snow. William’s father.

—That’s Miss Hale, pop. She drew my picture.

—William, I would appreciate if you addressed me as your father and not by that odious three-letter diminutive you’re so stubbornly fond of.

The young man mumbled “sorry” and winked a second time at me behind his father’s back.

—how do you do, Miss Hale?

He offered his hand, which I accepted and he smiled kindly while fixing me with his scrutinizing eyes. I felt I was being read like a book.

—I see where William gets his features from, Mr. Snow.

He didn’t respond to this, but turned to his son and said something about hurrying down to the hotel or mother would have the sacks of flour all loaded up by herself in this heat.

William took his leave, thanking me again for the “masterful study,” and told his father that I was owed two dollars.

—Honest wages, he added, winked one last time, and then ran off down the hill towards the town centre. I took my eyes off him sooner than I would have liked for fear his father would misread my gaze as something akin to lust.

—A lucrative enterprise, miss hale, charging two full dollars for a charcoal sketch.

—Your son seeks to take advantage of your kindness and my circumstances, I responded. The cost for the sketch is fifty cents.

He handed me a dollar and I turned to my cash box to make the change.

—Honesty is a priceless virtue, miss hale, worth far more to me than four bits. Please keep the dollar.

As he held the sketch at arm’s length and studied it in silence, I found myself suddenly apprehensive about what he wouldsay, as if he were judging me far more than my little drawing of his son.

—Not that I’m an expert in these matters, he said, or even experienced with the art form, but I must say, Miss Hale, that you have a fine hand for drawing. Here was a man of stature, obviously, in possession of both articulation and eloquence, delivering a compliment that was free of flattery. I attempted some eloquence in my reply.

—Thank you, Mr. Snow, but my hand is only servant to my soul, so in praising my work, you praise not my hand but my very mind and soul.

—And what is your mind and soul, my dear young lady, but an extension of the Lord God your Father? In praising your hand, I praise your soul and by praising that I ultimately praise him who furnished you with mind, soul and hand.

His voice modulated like an orator’s, and such crated delivery is designed not to elicit a response but to render the audience speechless and awestruck. And damn it, it worked like a charm. It’s not that I didn’t know what to say, it’s that I simply couldn’t say anything. I felt shaken—perhaps the word I want is stricken—and stood there like a dumb animal awaiting punishment or instruction from its owner.

He stood a moment, awaiting some kind of nod or sign of agreement or—who knows?—a jubilant “amen” or “hallelujah!” I still clutched the dollar bill in my hand, and realized that with it I had my train fare to Calgary. Knowing my voice would be dry and cracked and—worst of all—weak, I managed to press some words out of my mouth and salvaged some much needed shades of dignity.

—Thanks for the tip, I said.

I caught the 4 o’clock train to Calgary, and spent the next few hours watching the sun descend in the western sky and the play of dying light upon the wild prairie grass. I could not get the image of William Snow out of my head, his lightness and joy, nor could I rub clear the smudge let by his father.

To kill time—and space—I sketched a letter home… a simple profile of the young man who dreamed of molasses rum, a silhouette of his father in the background, with the following poetic inscription, compliments of dear Emily D:

Had I not seen the Sun

I could have borne the shade

But Light a newer Wilderness

My Wilderness has made—

Barry Thorson is a writer, theatre practitioner, tea store owner, and father, dividing his time between Cochrane and Banff.