Alberta’s most recent budget (2018–19) projected an $8.8-billion deficit—a shortfall of $2,024 per Albertan. Although that estimate was revised to $6.9 billion in the February third quarter fiscal update, this remains the province’s third large deficit stemming from the recession starting in 2014. Maintaining expenditures even as revenues drop unexpectedly is a sensible policy, one that economists typically recommend and that Alberta has pursued before (e.g., in 2010). Nevertheless, shortfalls accumulate as provincial debt, which must be repaid with interest. Albertans prefer to see their budgets balanced. So now that the economy is in (an admittedly moderate) recovery, when and how might that occur?

The NDP government has laid out a “path to balance” by 2023–24. The UCP claim they would balance the budget “by the end of their first term” (i.e., by 2023). No matter who governs Alberta, the task will be challenging.

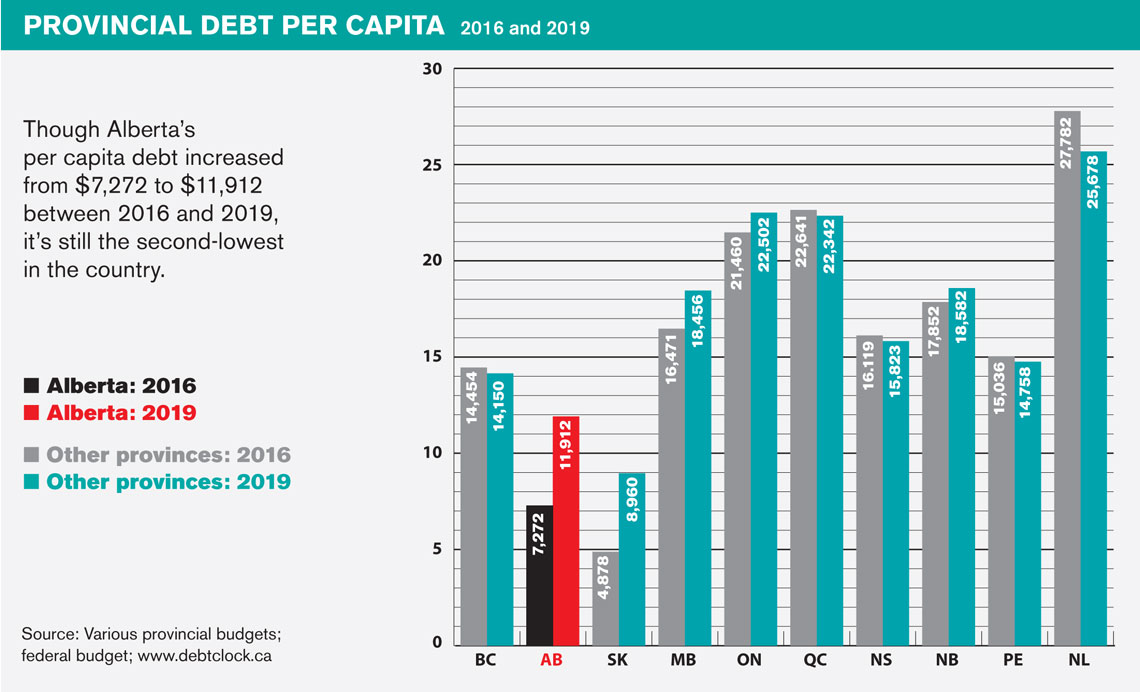

But first, the growing debt. The province’s accumulated debt is projected to be $96-billion (or about $20,000 per Albertan) by 2023–24. A large portion of that, however, will have been devoted to financing capital assets such as schools, hospitals and highways. While one can argue over the merits of borrowing for infrastructure investment—an approach likewise pursued by the Redford government—perhaps half of the accumulated debt in 2023–24 (compared to about two-thirds now) will have financed capital assets. This is rather like a home mortgage.

After accounting for the provincial government’s financial assets (e.g., the Heritage Savings Trust Fund), the net amount owing in 2023–24 is expected to be a more modest $56-billion. That is 12.3 per cent of GDP, lower than any other province today. As a percentage of government revenue, that $56-billion will be 84.5 per cent. Only two provinces, BC and Saskatchewan, presently have a lower level (both at 74 per cent) of net debt to government revenues. Other provinces’ levels range from 118 to 233 per cent.

Hence, although provincial government debt is increasing rapidly in Alberta, net debt per person is presently the lowest (by far) among the provinces. And even at its projected peak in 2023, Alberta’s debt level will be moderate compared to other provinces’, and quite manageable overall. Meanwhile, just over one-third of the post-2008–09 decrease in Alberta’s net financial assets (i.e., financial assets after deducting financial obligations) occurred before the most recent recession and before the NDP came to power.

Nonetheless, and rightfully so, Alberta is pursuing budget balance.

Source: Various provincial budgets; federal budget; www.debtclock.ca

To understand the problem and potential solutions, we must recognize how the province got into this situation. Is it a revenue problem or an expenditure problem?

Consider first the revenue side. From 2000 to 2009, provincial government resource revenues averaged $3,726 (real 2016 dollars) per capita. The collapse of natural gas prices saw those fall to an average of $2,447 from 2010 to 2015. The drop in oil prices in 2014 and 2015 resulted in resource revenues falling further, to about $700 per capita. They are projected to average $876 annually to 2021, and only improve to a nine-year average of $1,125 by 2024.

In short: Alberta’s 2015–2024 per capita resource revenues are expected to be more than two-thirds lower than those of 2000–2009.

And while resource revenues met 39 per cent of Alberta’s program expenditures from 2000 to 2009, they are expected to meet only 9.6 per cent of program expenditures from 2015 to 2024—one-quarter the contribution made a decade ago. In other words, our golden goose will lay much smaller eggs for the foreseeable future.

In fiscal 2017–18, the Alberta government spent $12,714 per person on programs and services (or $12,364 in real 2016 dollars). Program spending has averaged $12,064 (2016$) per person over the past decade. That is, over the past 10 years, the province has maintained spending equal to inflation plus population growth—a popular guideline among fiscal conservatives.

While these amounts may seem large, Alberta’s per capita total expenditures (program expenditures plus interest on provincial debt) have essentially equalled the average across Canada’s provinces since 2000, and program spending by itself has been only 6 per cent above the Canadian average. Indeed, Alberta has been an average spender for almost 20 years.

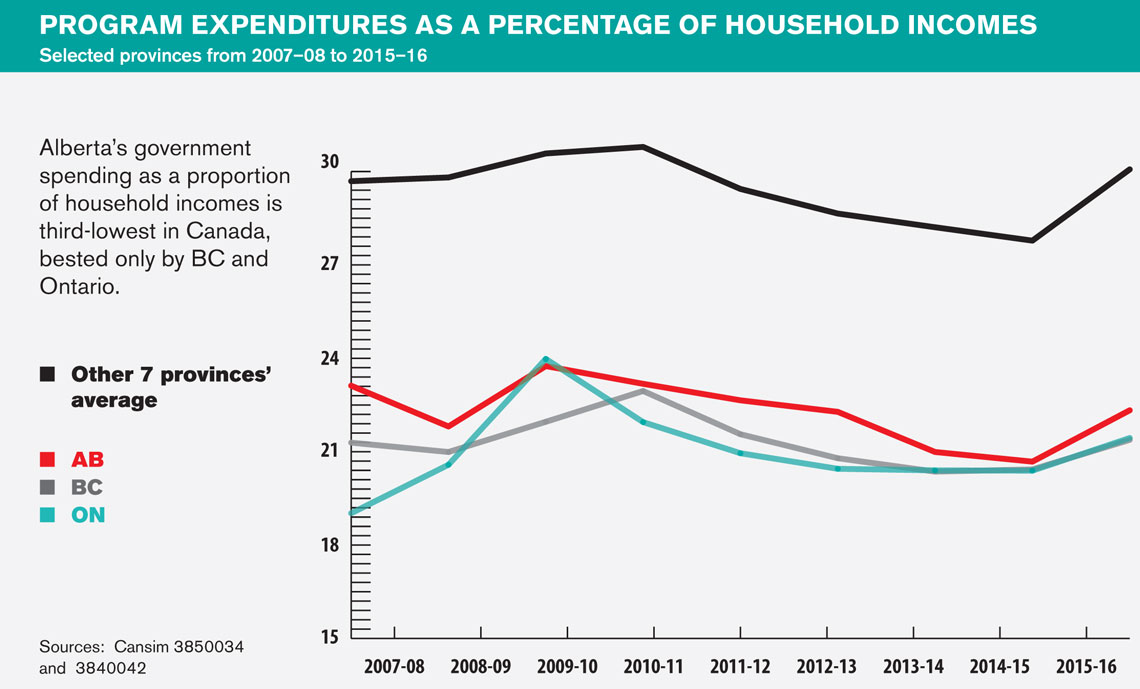

By still another measure, the province’s spending on public services has been surprisingly uniform. Since 2000, per capita household incomes in Alberta have increased 20 per cent in real, inflation-adjusted terms (even after the adverse effects of the recession). Over that time, program expenditures as a percentage of household income have seen very little year-to-year variation. The provincial government has represented the same proportion of the provincial economy since 2000.

Measured this way, Alberta’s program spending is quite low. Our 21.7 per cent level—relative to household incomes—matches those in the two lowest-spending provinces (BC and Ontario). Across the seven other provinces, program expenditures are 25–30 per cent of household incomes.

Albertans still enjoy high incomes and low taxes. We still have the highest per capita revenue-generating capacity of all the provinces.

It’s true that per capita government expenditures in Ontario and BC are about 20 per cent lower than Alberta’s. But household incomes in Alberta are higher (and are expected to remain so in the near future). This province has been and continues to be a high-cost environment (e.g., for labour, infrastructure and construction). For example, average weekly earnings are $1,144 in Alberta, $1,030 in Ontario and $978 in BC. More broadly, Peter Gusen’s 2012 Mowat Centre study estimated that costs to Alberta’s government (for the inputs needed to provide public education and other services) were higher than the average across other provinces. Calculations based on his data show costs here are 9.5 per cent higher.

The sky, in other words, is not falling. While provincial government spending has grown in Alberta since 2000, it has simply kept pace with economic growth. And our spending has stayed close to the average across Canada’s provinces—despite our higher costs.

If Alberta is to balance its budget while obtaining a much-reduced contribution from resource revenues, how might it do so?

In Budget 2018, the Notley government outlined its “path to balance.” While that plan shows no reductions in total spending, the size of the provincial government will shrink relative to the economy. Following the government’s projections, expenditures on provincial services will decline to 18.9 per cent of household incomes (a considerable reduction from the 21.7 per cent post-2000 average to which Albertans are accustomed). This represents a new low. The previous low was 19 per cent, incurred in 1998–99, which represented the depth of the Klein government’s cuts (cuts which were abandoned immediately thereafter).

Thus the Notley government has planned a gradual but substantial shrinking of government services—a reduction to a relative size comparable to that during the Klein-era cuts. That shrinkage is the result of fiscal restraint, growing interest on government debt, inflation, population growth and rising household incomes. As the “path to balance” demonstrates, in a growing economy, actual reductions in spending aren’t required in order to significantly reduce the size of government.

The fiscal plan of Jason Kenney and the UCP, the popular contenders for government, is (and will likely remain) less clearly defined. He plans to balance the budget a year before Notley does. The UCP has set a more challenging objective for itself. Spending cuts will need to be more severe because Kenney has said he’d reduce taxes. Eliminating the carbon levy (at least the consumer portion) is foremost, but Kenney proposes to bring back a flat-rate income tax (presumably at 10 per cent) and reduce corporate income taxes too. These moves could easily require reducing program expenditures to 17.9 per cent of household incomes—at least a percentage point beneath Alberta’s previous low.

Kenney’s fiscal musings suggest that his cuts would be quick and deep. But in fact, under both parties, the provincial government would become as small as or smaller than during the lowest point of the early Klein years. Expenditures on public services as a percentage of household incomes would fall by 13 per cent (from the post-2000 average) under Notley and by 18 per cent under Kenney. Both parties—but especially the UCP—plan to restore budget balance by reducing public services to unprecedented low levels.

Such cuts can be contextualized by looking at current provincial expenditures. Public sector compensation—about half of provincial expenditures—often draws attention. Although the Notley government quietly negotiated zeroes in all of its most important salary negotiations (with teachers, nurses, the AUPE and the Health Sciences Association of Alberta), a subsequent government might seek actual wage reductions. A 5 per cent cut would produce some savings initially, but long-term sustainability ultimately requires being competitive in the labour market, where the government vies with the private sector. The government could also choose to cut public sector jobs, but, since such employment hasn’t kept pace with population growth, that could pressure services.

Healthcare, Alberta’s biggest budget item, is also a ready target. The NDP government managed to bend the healthcare cost curve (with expenditure growth approaching 3 per cent annually compared to 6 per cent at the time of Notley’s coming to power) while maintaining health services. The UCP plan is for more privatization. That approach would shift some costs (and resources) to people who can afford private care, but reduce service levels for most Albertans, who rely on public care. Budget cuts might come from reducing or eliminating some publicly provided/funded health services—for example, Alberta’s pharmaceutical coverage and expenditures on services to seniors, both of which exceed those in BC.

A related but presumably less appealing option is to levy a premium ostensibly earmarked for health services, as in BC and Ontario, or a health and/or education payroll tax as in Manitoba, Ontario and Quebec. These could cost a $100,000-dual income four-person family in Alberta $900 to $2,559. As of 2009, Alberta eliminated health insurance premiums, which had generated about $1-billion annually; the Prentice government had proposed to reintroduce a more modest and progressive “health care contribution levy” in the March 2015 budget. A new government could do the same.

Capital expenditures are a common target for cuts, especially as the impacts are more distant than cuts to current operations. The Notley government expects to spend $6.4-billion this year on capital projects, $1.4-billion of which will be capital grants to local governments. The “path to balance” projects capital spending to decrease to $4.8-billion in 2023–24. During the Klein era, such provincial government investment was cut from $850-million in 1992-93 to $196-million in 1996–97. In addition, capital grants (primarily to local governments), which exceeded $300-million in 1992–93, were zero in 1996-97—an action that shifted costs to local taxpayers. During those years, capital assets deteriorated and Alberta was left with what is often referred to as an “infrastructure deficit” (in layman’s terms, leaky hospital roofs and overcrowded schools).

Sources: Cansim 3850034 and 3840042

Low resource revenues could mean that the price of public services falls increasingly to citizens. But Albertans might not choose to shrink the size of their provincial government. It’s unlikely we’ll want to cut services so severely, by the full amount of the decline in resource revenues. To do so might well result in Alberta having the lowest level of provincial services in Canada. Resource revenues have dropped, but not the need for education, healthcare, roads etc. Notably, the Klein cuts had been reversed by 2001. As low resource revenues make us more like other provinces, Alberta’s fiscal tools may need to become more like other provinces’ too.

Fortunately, Albertans have options. We still enjoy high incomes and low taxes. Despite lower resource revenues, Alberta still has the highest per capita revenue-generating capacity of all provinces. Consequently, we still have a tax advantage. Our provincial taxes relative to incomes are the lowest of any province. Our tax advantage is so substantial that additional taxes here could cover 2018–19’s projected deficit of $8.8-billion and still leave a tax advantage of $2.4-billion over the next-lowest-taxed province (BC). That is, if Albertans had BC taxes, we would pay $11.2-billion more—and we’d still be tied for Canada’s lowest-taxed citizens. We’d pay $14.1-billion more if we had Ontario’s taxes. As economic recovery proceeds, Alberta could probably finance its existing level of services relative to household incomes and still have about a $6-billion tax advantage over the next-lowest-taxed province.

In these circumstances, a probable outcome is a somewhat reduced but still acceptable level of public services funded by additional revenues. What might the sources be? Higher income tax rates risk making Alberta less competitive; new healthcare premiums/taxes would likely be insufficient. As low resource revenues make Alberta’s fiscal environment more comparable to other provinces’, Alberta’s fiscal tools may need to become more like other provinces too. As the only province without a sales tax, the choice seems clear (although no political party dares acknowledge as much): a moderate sales tax would allow Alberta to balance its budget and provide comparable services while retaining a tax advantage.

Albertans may have little choice but to act soon and decisively. Revenue and expenditure projections by U of C economist Trevor Tombe suggest that the early 2020s may actually be a sweet spot for the province—when the difference between revenues and expenses is at its smallest. Indeed, Alberta’s budget imbalance is projected to expand thereafter (post-2025).

At that point, confronted by expenditure growth driven by an aging population and resource revenues that fail to keep up, our budgetary choices will not become easier. Delay could prove costly.

Mel McMillan is a professor emeritus in the department of economics at the University of Alberta.