by Photographs by George Webber, with contributions by Fred Stenson and Rosemary Griebel

Rocky Mountain Books

2018/$45.00/320 pp.

Photographers face fierce competition nowadays. Even five-year-old children snap pictures, and the smallest minutiae of the day fill the internet. Photography has become the lingua franca of our globalized world. Yet amidst the throng, only a few unique talents create images that are lasting, powerful and, like all great art, intangible. George Webber is among them.

His career started in the 1970s, when Webber began to photograph what he knew best—the area around his hometown of Drumheller. In the following decades, his work was awarded and featured in national and international collections as far away as the Australian National Gallery. But Webber never strayed far from his southern Alberta roots. His books have immortalized such quintessentially local sites as First Nations reserves and Hutterite colonies, among many others.

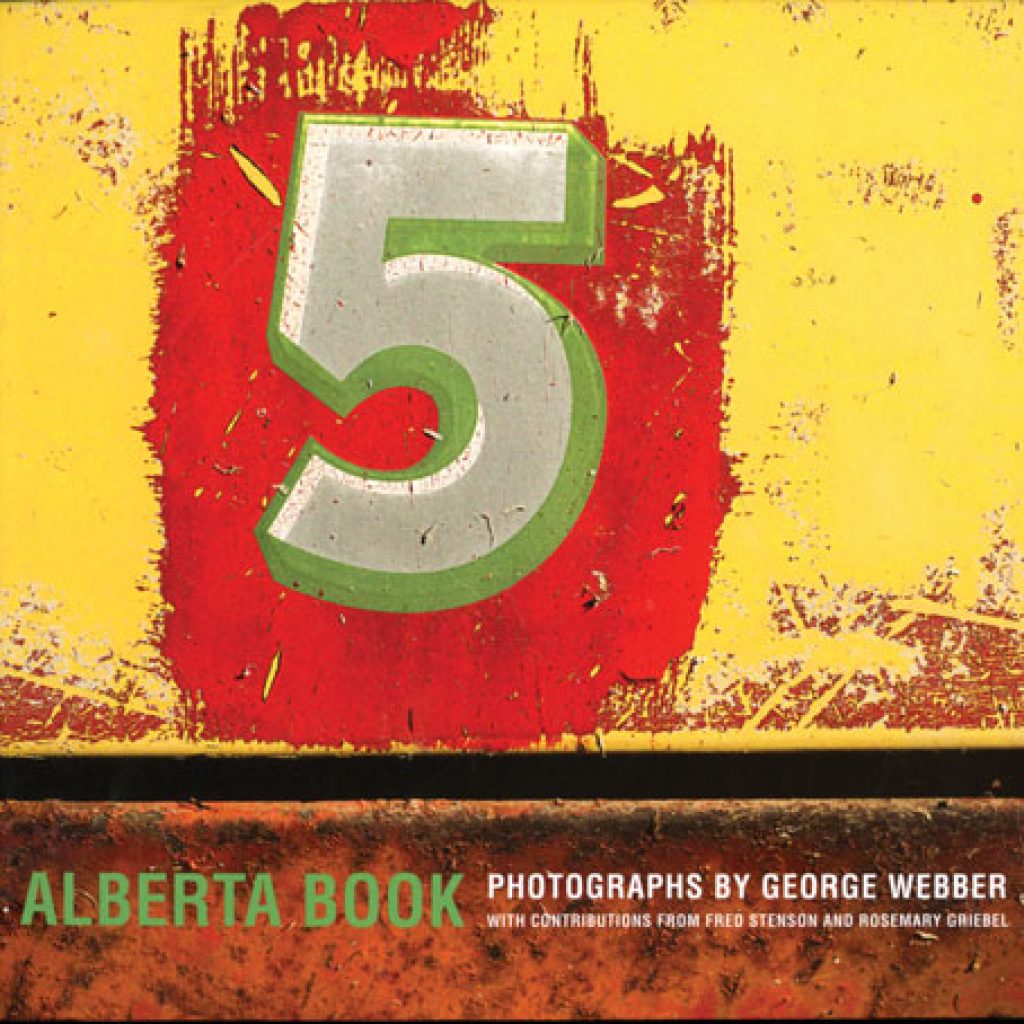

In his eighth collection, Alberta Book, Webber returns to the places of his childhood—the rural communities he watched flourish and decline to near ghost towns. His photos are not pretty. There is plenty of rust, peeling paint and desolation. In fact, out of the 251 photos taken over 39 years that Webber selected for this book, only one depicts a distant silhouette of a pedestrian. In these photos, rural Alberta is filled with boarded-up buildings and seems eerily devoid of human presence. Businesses and their cheerful Coke or ice cream ads have become windswept relics. Some might argue that these towns have a face only a mother could love. But that’s exactly what makes these images magnetic.

An intense affinity with his subjects allows Webber to reveal the cast-aside as beauty and embody the words of sculptor Auguste Rodin: “There is nothing ugly in art except that which is without character, that is to say, that which offers no outer or inner truth.” Such alchemy is evident in Webber’s previous books, including his collection of Calgary’s destitute East Village residents: Beams of light stream through narrow windows and illuminate marginalized men. They now resemble precious Vermeer paintings. The same transformation is evident in Webber’s new book, only here it is vacant gas stations and forsaken Chinese takeouts that become living portraits.

Here too the haunting quality of light persists, making architecture appear almost anthropomorphic. For example, in “Lougheed, Alberta, 1987,” the sky turns a dark indigo blue. In the centre of the composition a concrete sidewalk leads far into the approaching storm. Side lit, as if characters in a theatrical play, two buildings glow in the remaining rays of the sun. In a few seconds, darkness will descend and these humble businesses will again seem ordinary and easily overlooked.

Time’s passage is central to Webber’s photography. His buildings proudly display their wrinkles—each crack and falling clapboard relates stories of people who built and lived among them. Amidst the decline, Webber shoots a few freshly repainted facades. Their bright cyan blues and carnelian reds offer signs of life amidst vast ochre landscapes. These are living towns—not frozen-in-time historic artifacts. Behind Webber’s lens, Alberta’s story continues and endures.

Webber’s art strings paradox upon paradox. Time is stilled, yet alive; ramshackle buildings along highways take centre stage; detritus becomes high art. The contradictions that this book uncovers amidst ordinary towns boggle the mind. It’s no wonder that Webber returns over and over to his beloved prairies—often visiting the same sites through decades. He sees what most of us overlook: The strength and beauty of character that permeates rural Alberta.

Agnieszka Matejko is an artist, writer and teacher in Edmonton.

_______________________________________