In an increasingly urban and self-consciously cosmopolitan province, something about the word “rural” seems to make people uncomfortable. Whatever the lingering mythic importance of ranchers, pioneer farmers and wide-open spaces, stored safely away in the past like Stampede-week playclothes and boots, the rural Alberta of the present is caricatured more commonly in terms of redneck backwardness. It is the dead weight on the world-class aspirations of major cities. It is the domain of all those uncultured county reeves in plaid jackets who move on to become MLAs.

Certainly rural Alberta has become an unfamiliar place to most people. Apart from the high-priced acreage and recreational enclaves that have colonized its prettiest spots, rural is not so much a destination as a transportation corridor between cities. More than that, it represents a resource plantation—sites from which wealth is extracted by workers whose homes are elsewhere. As family ties weaken by the generation and in-migration continues at a feverish pace, there are few other meaningful connections to rural places.

For that matter, those places are increasingly out of step, in measurable ways, with Alberta as a whole: they are older, whiter, less educated, their populations often declining and their per-capita incomes lower, even in resource regions. While cities build for growth, smaller rural communities outside the Calgary/Edmonton corridor hope, at best, to hang on defensively to local schools, hospitals, stores and banks.

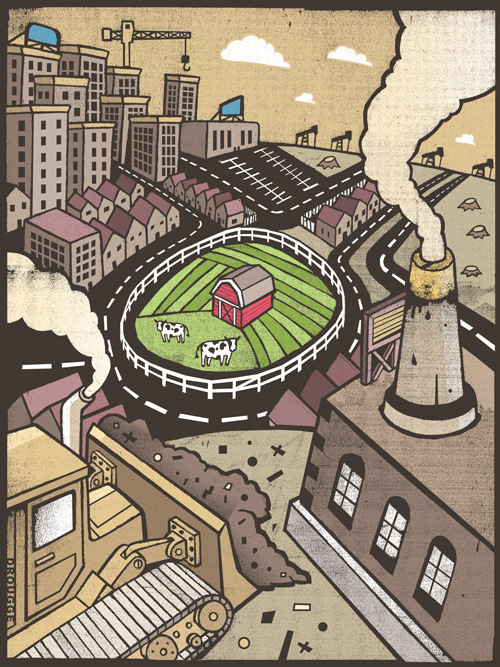

That description may be exaggerated, but only slightly. It captures what has become a complicated political faultline in Alberta and a difficult starting point for any public conversation about which rural future we want. In the absence of such a conversation, the answer is being decided on the ground. Out of sight, out of mind, rural Alberta is already the site of intense land- and water-use tensions. Their resolution will do more than determine the look of a local landscape: it will shape what is possible, or not, for the entire province.

My main interest lies in two related long-term ecological trends in the countryside. They ought to worry every Albertan who eats and who is not complacent about the food that now appears effortlessly on grocery store shelves. One trend is that farmers and ranchers—people skilled at producing food—are fast becoming an endangered species. The other is that the physical habitat for farming and ranching is disappearing or has become less hospitable with the encroachment of industrial, residential and other land-use pressures.

Farmers and ranchers—people skilled at producing food—are fast becoming an endangered species.

The first trend is a matter of numbers. The 2006 Census of Agriculture registered another five-year drop (7.9 per cent) in the number of farms across Alberta—now fewer than 50,000 for the first time since the early homestead era.

Not surprisingly, the census also showed significant increases in the average age of farmers (from 49.9 to 52.2 in Alberta) and in the percentage of farmers engaged in full-time off-farm work. It suggested a further hollowing-out of the family-farm sector while the largest operations grew in size.

Even more striking as an indicator of farm exodus was a Statistics Canada study in 2002 that found a drop of about one third—larger in Alberta—in the number of people across the prairies whose declared primary work was agriculture. That drop occurred in only a four-year period, 1998 to 2001, before the worst years of drought and the BSE crisis.

The only trouble with numbers and trend lines is the sense of historical inevitability that attaches to them—as if any attempt to reverse them would be futile.

Numbers hide the anguished individual choices and the shifting hand of public policy that together affect farm populations and rural communities.

For several decades following Confederation, the settlement of the Canadian prairies, primarily for export grain production, mattered a great deal. It was the national policy. To that end, the national government negotiated treaties with aboriginal peoples involving real obligations; it sponsored rail construction; it recruited immigrants and established experimental farms that adapted seed varieties and, for better and sometimes worse, instructed settlers on how to adapt to the growing conditions they found.

Since at least the 1960s, however, in both national and provincial capitals the policy pendulum has swung decisively. The lead assumptions have been, first, that the problem with viability in agriculture is that there are too many farmers, and second, that full exposure to market discipline will weed out those who are not large, technology-savvy and credit-worthy enough to stand on their own in a competitive global food system. Get big or get out.

In effect, farmers increasingly have been left to fend for themselves. They operate under intense pressure at the most vulnerable end of so-called commodity value chains. There is money being made in prairie agriculture, but increasingly it flows through farmers’ hands; this reality is reflected in the growing gap between their gross and net incomes.

At the same time, farmers are fair game for newspaper columnists quick to spot a “bailout” to a “chronic subsidy industry.”

The question of whether there will be a successor generation will be decided within the next decade.

There is nothing unique to Alberta or to Western Canada about farm exodus or the challenge of rural development. But there is a special intensity to the issue in this boom-addled province. For one thing, Alberta is now among the most urban provinces in the country. By 2001, more than four in five residents lived in cities; some of the rest lived in the “donuts” of bedroom communities and acreage subdivisions around major cities. The Edmonton/Calgary corridor is one of the fastest-growing metropolitan regions in the country. Recreational and residential pressures on land prices make it attractive for farmers to sell out and buy land in eastern Saskatchewan, or retire, but they also make it prohibitive to buy for conventional agricultural uses.

Growing cities are voracious consumers of farmland and water. While Albertans have begun to develop interest in local food sources, the municipalities in which they live have been more successful in adopting their own version of the 100-mile diet. By 2001, urban encroachment on “dependable agricultural land” (class 3 and better) across Canada had more than doubled since 1971 to 14,300 square kilometres. That figure does not account for the effect of pushing golf courses and other urban-perimeter activities further into the countryside. As for water demands, the population of the South Saskatchewan River basin grew by 450,000 people, almost all in cities, between 1981 and 2001, while downstream flows continued to decline.

If farmers and ranchers are an endangered species, it is partly because their habitat is under stress. In addition to urban sprawl, parts of the rural prairies have become increasingly industrialized as resource plantations, transportation corridors or landfills. They absorb in a concentrated form the messes of large-scale production and consumption. Location, it turns out, still matters.

Whether it is emptying out or filling in with new subdivisions, rural Alberta is the site of conflict involving a range of alternative futures. For example, a circle drawn at a 100- kilometre radius around the small, growing city of Camrose, where I live, would encompass some of the best farmland in Canada. But it would intersect the new housing developments in southeast Edmonton and in bedroom communities along the major highways—plus the requisite golf courses.

It would also include a good number of the 6,000 coalbed methane wells drilled in Alberta in the past half decade; some of the 200,000 oil and natural gas wells operating in Alberta (20,000 new ones in each of the past two years); a sizable share of Alberta’s almost 300,000 kilometres of pipelines; the gravel pits that are mined intensively to build concrete basements for housing developments; a landfill near Ryley—with room to grow to 11 quarter sections—that will take garbage from Edmonton and perhaps soon Vancouver, shipped by rail, and that has room and a secure enough clay liner, its boosters say, for all of Canada’s garbage for the next century; a proposed coal mine and gasification facilities in the same county that, if approved, will mean the excavation of more than 300 square kilometres of land over 40 years to produce energy to power Alberta’s oil sands extraction.

Just outside the eastern edge of the circle, what would have been the largest hog-barn complex on the prairies was blocked by a determined political and legal fight by local residents. On the western edge, a proposed north/south transmission line for the export of electricity is now the subject of a divisive regulatory hearing.

A society that loses the collective skill to produce food is less free in every practical sense of the word.

Local coexistence in rural communities is, of course, always complicated; farm people sometimes depend on oil-patch work and industrial contributions to the municipal tax base. But some forms of development eventually preclude others. It is no exaggeration that in parts of rural Alberta, family-farm agriculture has been reduced to the status of a secondary, tolerated land use, permitted so long as it does not impede more intensive and profitable adjacent uses.

The question of who will own the countryside, live in it, care for it or produce food from it is far from settled. What is fundamentally at stake in the outcome is this: a society that loses the collective skills to produce food is less free in every practical sense of the word. It is hostage to what is now a highly concentrated, hydrocarbon-based, long-distance food system. That system is marked by dwindling global reserves and sensitivity to energy-price shocks in both production and transportation. Since it involves fewer, larger processing points, it also presents tempting targets, as commentators have begun to note, for terrorist action.

For the sake of a more resilient food system, it matters that large numbers of farmers and their children see no future in farming and that therefore the intergenerational skill base is thinning out. It matters that the habitat for human- scale agriculture is subject to relentless encroachment and little protection. And it matters that, even when a BSE crisis temporarily shuts the border and invites alternative thinking, there is little intelligent discussion of food policy in Canada.

The sustainable food economy of the future, on the other hand, will almost certainly be a more local and regional one. It will have to be supported by intelligent, balanced, protective land-use strategies. It will be fitted to the limits of a dry climate and a fragile ecosystem. It will require a closer alignment of agriculture, environmental and economic development policies. Among other things, that will mean a partial shift away from high-volume strategies, which are designed to produce cheap, uniform food-and-fibre material either for export or to attract large-scale “value-added” industrial processors. The shift may be as hard on farmers as on governments.

The new food economy will need to make room for smaller- scale forms of agriculture in which the capital barriers to entry for the next generation, including new immigrants and urban refugees, are not prohibitive. In other words, it will require more farmers, not fewer. Such a reversal will only happen if farmers are equipped with enough market share and enough tangible recognition of their environmental responsibilities that they can produce food in sustainable ways. The very real alternative is a countryside turned over to pavement, pump- jacks, playgrounds and deep-pocketed speculators. There will still be pockets of agriculture, on land owned by people who mostly live elsewhere, but it will be left in the day-to-day hands of employees and tenants who do not necessarily have the kind of long-term stake in a place that nurtures communities, knowledge and an appropriate standard of care. It will also be indifferent to local markets.

Scholars and policy-makers are now careful to disentangle “rural” and “agriculture”—assuming that the fate of one no longer rests on the other. The separation rightly draws attention to the diversity of rural communities and the difficult economic realities in agriculture. There is now less economic reliance on farming. Past a certain point, though, the separation becomes a dangerous self-fulfilling prophecy.

In Alberta, food policy ought to intersect with rural policy in significant, innovative ways. If not in the countryside, where else? We are living in a time when the choices are immediate. We are living in a province where the combination of public resources and local knowledge can still make us leaders—in our own long-term interest, if nothing else.

Roger Epp is dean and professor of political studies at the University of Alberta’s Augustana Campus in Camrose.