Laurence Decore made a panicked phone call to his campaign manager during his first run to be mayor of Edmonton. As manager Jim Lightbody recalls, a woman had told Decore that she was considering voting for him, but was concerned he was a Liberal. The year was 1983; the Alberta economy was tanking and many people blamed it on the National Energy Program of the Trudeau Liberals in Ottawa. “Liberal” was a dirty word in many quarters in Alberta.

But Lightbody, who was then a University of Alberta political scientist specializing in municipal governance, had some advice for Decore. “I said to him: ‘I would tell this citizen there is no Liberal or Conservative way to pave a street.’”

Most Alberta municipal politicians, no matter where they get their money from or who their allies are, would agree with that statement. They say their decisions are based on common sense, for the good of the city. After all, how can you put a partisan spin on collecting garbage, laying pipes, fixing potholes or paving streets?

However, underneath the non-partisan veneer of municipal politics beat a lot of partisan hearts—and the blood they pump through their veins has a wider spectrum of colours than the Tory blue that dominates provincial and federal politics in Alberta.

New Democrats regularly pull in a minuscule fraction of the vote in federal and provincial elections, yet in cities and towns from Medicine Hat to Claresholm these same candidates manage to win council seats and even the mayor’s chair in municipal elections.

“I think you’re the best candiate,” provincial voters say. “It’s just too bad you’re with that party.”

Avowed New Democrats and Liberals have occupied the mayor’s chairs of Calgary and Edmonton. Even Calgary Mayor Dave Bronconnier, who has won three campaigns (two with huge majorities), had no success a decade ago when he ran federally for the Liberals against then-Reformer Rob Anders in Calgary West. Previous mayors, including Al Duerr and even Ralph Klein in the 1980s, were proudly Liberal. Calgarians have not elected a New Democrat MLA since 1989 and have never elected an NDP MP, yet they consistently elect and re-elect aldermen with strong NDP roots, such as Bob Hawkesworth.

Edmonton, which has been friendlier to opposition parties, has had something of a revolving door with the provincial legislature. Decore went on to lead the provincial Liberals, while councillor Brian Mason left civic politics to eventually lead the NDP. The city currently has three councillors who are former Liberal MLAs.

Brian Pincott is very aware that someone with his environmentalist, left-of-centre views would not have much of chance of being elected to the legislature or parliament by Calgarians. The co-founder of the Calgary branch of the Sierra Club, Pincott ran twice for the federal NDP in Calgary, picking up only 6 per cent and 12 per cent of the vote in the 2004 and 2006 elections. But he managed to get himself elected to Calgary city council in 2007 on his first try, something he acknowledges would not have happened if he had been running under a party banner.

“It’s odd that I was elected, when you look at the people I represent,” Pincott says. His Ward 11 overlaps with the federal constituency of Calgary Southwest, the riding of Prime Minister Stephen Harper, and the provincial riding of Calgary Elbow, held for 18 years by former premier Ralph Klein.

Opponents raised Pincott’s NDP roots during election forums, and he didn’t hide them. He answered that he was representing community values of a viable, sustainable city for all residents, and voters bought the progressive package.

“I didn’t run as a New Democrat—I ran as me,” Pincott says. At the municipal level, “you can stop carrying the baggage of political parties and engage the voters in ideas about what they want the community to be.”

Parties have never played a part in Alberta city politics. While there have been coalitions and pressure groups, they had nothing like the coherent platform of federal or provincial parties or the municipal parties of British Columbia and Quebec. Edmonton has had business booster coalitions like the Citizens Committee that helped Bill Hawrelak become mayor in the 1950s, and Calgary had the similar Calgary Urban Party. More recently, Edmonton’s left wing and environmentalist groups engineered slates of candidates, such as the Urban Reform Group of Edmonton, the Edmonton Voters Association and Clean Slate in the 1990s. But they never operated as parties.

In the 2007 Calgary civic election, the Better Calgary Campaign endorsed a slate of candidates, but with a non-partisan bent. Eight of the 10 candidates endorsed by the campaign won, and they ranged from ultra-conservative Ric McIver, nicknamed “Dr. No” because of his reluctance to spend taxpayers’ money, to Pincott.

Naheed Nenshi, spokesman for the Better Calgary Campaign, says the candidates were chosen on the basis of their vision for the city on issues like transportation and urban sprawl, not for their partisan political leanings.

“Our argument is that municipal politicians are not on the left or the right wing,” Nenshi says. “People are on the same page no matter where they stand on the political spectrum.”

Municipal politicians say they are judged by their individual abilities and work ethic in serving their constituents on practical matters, rather than by the political banner they carry. And they don’t need to win a party nomination race to run for office—all they have to do is put down a small deposit and get a few dozen names.

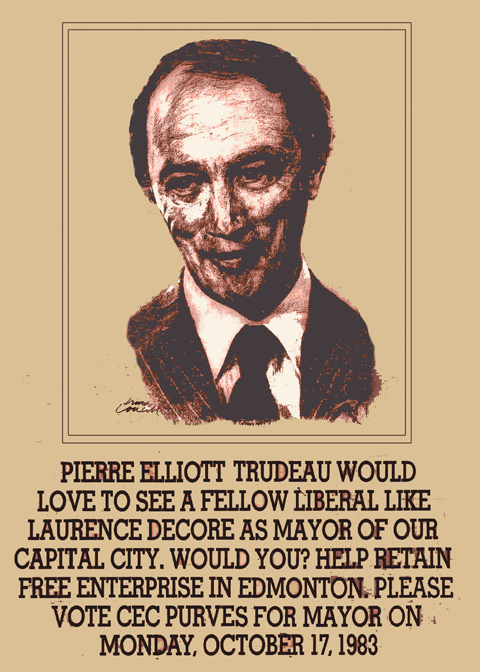

Many local politicians have belonged to a political party, raised funds for a party and worked for candidates and run for office, but attempts to brand them by their political ties have usually backfired. On civic election day in 1983, Peter Pocklington, the controversial former owner of the Edmonton Oilers and the Gainers meatpacking plant, placed a full-page ad in the Edmonton Journal highlighting Decore’s support from then-despised-in-Alberta prime minister Pierre Trudeau. Decore won by a huge margin despite his Liberal ties. Six years later, NDP supporter Jan Reimer won the first of two terms in the mayor’s office despite attempts by her opponents to label her a “socialist.”

Peter Pocklington took out this full-page ad in the Journal in 1983. (Calgary Public Library Archives)

Lightbody says the non-partisan tradition in most Canadian cities goes back a century and a half, and it has persisted. None of the functions of the city—as court, corporation or site of direct democracy—are thought to blend in with notion of partisan politics, where the will of the caucus, the platform or the party leader dictate the stance of individual politicians.

The voter is looking for something very different when going to the polls in a municipal election. Lightbody calls this “caretaker politics,” where the voter supports the candidate he or she feels is best able to ensure that the garbage is removed and the streets are plowed, rather than their ideological stance.

“There’s a sense that city politics is not political, [that] it’s management,” Lightbody says. “In Britain, they call it ‘low politics’ at the town hall in contrast to the more ‘noble’ venture at Westminster.”

No doubt, the way municipal functions are managed has an ideological content. Is the work contracted out or done by the city? Is it paid for by progressive tax or a flat fee? But Lightbody says voters care much more that the task be done efficiently; public or private venture, expensive or inexpensive, what matters most is value for money. The urgency and visibility of an issue seems to translate into more non-partisan thinking; the average citizen gets more riled about the ruts in the snow on his street than about the sale or non-sale of a city asset. All of this means that someone who would never think of voting anything other than Tory provincially is willing to overlook the NDP past of a candidate in the interest of getting the job done.

Hawkesworth thinks the lack of partisanship in Alberta city politics could have a lot to do with the ward system. He doubts that voters want the councillor representing their ward to also be beholden to a party platform.

“In local government, there is a strong identification between voters and elected representatives, much more than legislatures or the House of Commons, which are quite distant and they represent large populations, so an individual gets lost,” he says. “When you’re a city councillor and it’s your ward, your neighbourhood and your street, you’re more identified as the elected representative. The loyalty is more personal.”

The idea of running as an individual, not as a disciplined member of a caucus, lured Don Iveson to municipal politics in Edmonton. The 29-year-old upstart, who confounded the pundits by defeating ultra-conservative Edmonton city council veteran Mike Nickel in 2007, finds the municipal level of politics more competitive and focused on issues.

“Most of the time in federal and provincial politics people vote for a platform and a leader,” Iveson says. “[Municipal politics] doesn’t have the extra layer of baggage. You’re really your own person, and that’s what attracted me.”

Political scientists point out that voters’ decisions in provincial and federal elections are often based on factors such as how their parents voted, and that voters sometimes “hold their noses” and vote for a candidate they don’t personally like but who happens to be from the right party. For instance, Rob Anders, the MP who once called Nelson Mandela a terrorist and who is regarded by many members of his own party as a permanent, second-rate backbencher, has never had trouble winning elections in Calgary, where voting for federal Tories (or Reformers) has been deeply ingrained since at least the early 1980s.

Iveson was once a provincial Liberal party member, but now considers himself non-partisan and credits his surprising election win to that non-partisanship.

“My politics are confusing enough that I was asked by all four parties to run for them (in the provincial election),” he says. “I had a lot of different people… work on my campaign, people from every political stripe. I take a lot of pride that they were working toward the same end.”

Don Braid, a columnist for the Calgary Herald and long-time observer of both provincial and Calgary municipal politics, says Calgarians are willing to overlook Liberal and NDP party labels if they are convinced the candidate is competent and will look out for their interests.

One of the biggest fears about Liberals in fiscally conserv-ative Calgary goes back to the 1970s when the Trudeau government racked up huge deficits and sent the country into debt, Braid says.

“Even though a lot of Calgarians don’t like Liberal government, they know that with city council they don’t have that worry because city council isn’t allowed [under provincial legislation] to run a deficit.”

Brian Mason agrees that it is much easier for a NDPer to get elected to a local council on the basis of their individual abilities and without a party label. Albertan cities and towns that almost always elect federal Tories by a comfortable margin have elected New Democrats as mayor, including Ted Grimm in Medicine Hat and Ernie Patterson in Claresholm. (Medicine Hat voters also elected former provincial Liberal Garth Vallely as mayor, while current Grande Prairie mayor Dwight Logan ran provincially as a Liberal in 1993.)

“What we hear often from rural Albertans is: ‘We think you’re the best candidate, but it’s too bad you’re running for that party,’” Mason says.

The irony is that city councillors, whose vote carries the same weight as the mayor’s, have a lot more power than MLAs, especially those in opposition, he says. Backbench and opposition MLAs or MPs have little say on government policy, and many decisions are made outside the House in the form of Orders in Council.

Linda Sloan has spent much of her adult life fighting the Tory government, first as president of United Nurses of Alberta and then as a Liberal MLA, but she’s spent the past four and a half years as an Edmonton city councillor. She finds representing her west end ward much more rewarding than being in the wilderness of a small opposition.

“There’s a lot more accountability at the municipal level of politics,” Sloan says. “There are fewer of us. And council is more visible, as the services we make decisions about are ones that people use every day, which have a direct impact on their quality of life.”

One of the refreshing aspects of municipal government for Sloan is the accessibility and non-partisan nature of the bureaucracy. When she was an opposition MLA, she had difficulty gaining access to information and to the bureaucrats themselves, but at the city level the administration is not politicized and is much more accessible.

While political parties are formally absent from municipal politics in Alberta, partisanship does occasionally rear its angry head.

Mayor Bronconnier, in his attempts to get more provincial funding for Calgary, had a long battle with the province during which he accused premier Ed Stelmach of breaking promises. Bronconnier even included a letter critical of the provincial budget with the 2007 city tax notices. “When the rhetorical dust had cleared, it was obvious the budget had not delivered what was promised,” he wrote. “The consequences of inaction, or half-steps, will be felt by ourselves, our children, and our grandchildren.”

The Tories’ loss of Ralph Klein’s old seat in a 2007 by-election was largely blamed on this battle. Cabinet minister Ted Morton accused the mayor of being driven by the motive of wanting to one day run for the leadership of the Liberal Party.

Braid says there is no love lost between Stelmach and Bronconnier, even though the province eventually came through with a long-term funding formula acceptable to the City of Calgary. “The Conservatives would love to get a strong Conservative mayor,” Braid says.

He watched a Conservative cabal on council foment something of a tax revolt during the November budget discussions after a 9.8 per cent tax increase was proposed. Braid calls this the classic ideological conflict that happens when times get tough: liberals want to continue spending on services while conservatives react by trying to cut spending. The tax increase was whittled down to 5.3 per cent.

There are no decisions with more potential to create ideological divisions than the privatization of city assets. The sale of Edmonton Telephones in the 1990s accentuated a deep schism on city council, and Calgary council experienced similar rancour over the proposed sale of Enmax, which eventually was voted down.

Edmonton council recently grappled over a proposal to sell its state-of-the-art Gold Bar wastewater treatment plant to Epcor. While Epcor is owned by the city, it is an arm’s length corporation with its own board. Civic unions and other groups formed a movement staunchly opposed to the sale, calling it a step toward privatization of city assets (the sale went through).

Iveson is typical of most municipal councillors when he says his vote against the sale was based not on ideology but on what was fair and in the best interests of the city.

One of the major functions of a municipality, of course, is managing land use, and Sloan sees the fate of agricultural land in northeast Edmonton as a potentially divisive political issue. At recent public hearings on the Municipal Development Plan, farmers and greenhouse owners made a plea for a food security strategy that could save some of the land in that fertile area with a relatively warm microclimate from being paved over for new residential suburbs and heavy industry.

Mason says land use is a major ideological issue in local government, and developers play a big part in funding electoral campaigns to get a supportive council. While the money isn’t as big as in province-wide campaigns, mayoral campaigns, such as Bronconnier’s in 2007, can cost over $700,000.

“Until the civic unions organized to counterbalance the development industry, you had constantly conservative councils in Edmonton,” Mason says. Still, election declarations by Edmonton city council show significant contributions by the development industry to most councillors. Numerous developers contributed more than $5,000 to the campaign of Mayor Stephen Mandel, the largest donor being West Edmonton Mall Properties Inc., which gave $26,500, followed by $20,000 by companies controlled by Rexall and Edmonton Oilers owner Daryl Katz, who is looking for city support to build a downtown arena.

In Calgary, developers and construction companies also factored prominently in the list of donors to Mayor Dave Bronconnier’s 2007 campaign, with the largest donation ($20,000) coming from Devitt & Forand Contractors. Even “progressives” like Pincott received substantial donations from developers. However, he doesn’t view his hard line against urban sprawl as being anti-development. Once council decides on the vision of a higher-density city, developers can still make just as much money, he says, even if they are doing it differently.

While paving a street may not adhere to partisan values, there are still very different ways to do it.

Sometimes city councillors’ beliefs conflict with their duty to serve the ward they represent. In municipal politics, the ward typically wins.

Iveson has said the day he found himself having to support a P3, a public/private partnership favoured by fiscal conservatives, was the day he came of age as a politician. He doesn’t support P3s, because he believes relying on a private owner to maintain city facilities for decades could shorten their life. But he still voted for a proposal to build a recreation centre in his ward using a P3.

“I thought there was a possibility the recreation centre might not happen at all, that this was the only way it would be built,” he says. “I had a lot of doubt about the process, but if there was no centre because we didn’t like the delivery model, that was a greater loss for the community.” Iveson says he was relieved when the proposal fell apart and the city reverted to a more conventional method of building the recreation centre after the consortium of companies said it could not deliver a project of the scale the City wanted for the quoted price.

Iveson’s experience shows that while the ways of building rec centres or paving streets may not exactly conform to either Liberal or Conservative values, there are still very different ways to do them. In the end, it is the will of the people, not the crack of the party whip, that compels Alberta’s municipal politicians to take action.#

Mike Sadava is a freelance writer and a former city hall reporter for the Edmonton Journal.