I knock on the door of Room 701, a little softly, hesitating to interrupt the conversation of strangers. Twenty-five adults are sitting together in a semicircle of desks beside a wide window. Sunlight rests on their shoulders. It is early morning in downtown Edmonton, and this is the first English class of the day at NorQuest College. The teacher, Judy Carter, has explained to them that I am here to ask for their best ideas.

They establish the rules of our encounter first. They will decide whether to speak or not, and whether to identify themselves. I will write down their sentences in my blue notebook, then type them later, so they can read their English words on separate pieces of paper. They will fix these sentences, after thinking about them, and I will return to pick up their corrections.

They ask me to repair spelling and grammar mistakes, but to preserve every spoken word exactly as they have expressed it.

They are ready to speak their minds to anyone in Alberta who will listen.

“My point to the government of Canada is this. They say they want to bring thousands of people here to work. Coming here is not an easy thing. We immigrants are already here. Couldn’t the employers hire us? If I have kids at home, I couldn’t bring them here. I wouldn’t have the money. I have to pay back the landing fee for me. This is difficult.

“We have many people here with qualifications. They have a diploma. They are driving a taxi. Canada, you can’t bring somebody to be a cleaner in your city for $7 an hour for ten years! I lived in Toronto, and in Alberta. Both are the same. Canada is the same across the whole country. I have been working at cleaning for $7 an hour.”

—Angelo Mawien

Six years in Canada, originally from Sudan

They are the true experts on immigration policy, these newcomers. With their blunt observations and smart suggestions, they would like to nudge that slow and cumbersome beast, the Canadian immigration system, out of the muck of inertia. The students of Room 701 are not well acquainted with the prime minister, the premier, the federal and provincial cabinet ministers, the political parties, or the senior civil servants who make critical decisions that shape their future. They have only heard that Alberta is desperate to recruit at least 24,000 new immigrants per year to ease the province’s severe labour shortage, a problem that is evolving into a public emergency from High Level to Cardston.

Everyone in Alberta knows about the shortage of workers. Our expanding economy is expected to create 400,000 new jobs between 2004 and 2014, but the province estimates only 300,000 Canadian-born workers will enter the job market here. That will mean a shortage of 100,000 workers, not just in the new industrial projects and housing construction, but also in schools, hospitals, grocery stores, banks, libraries, public transit, the arts and other vital public services.

Consider the now hiring signs in every corner of Alberta, and start multiplying. By 2015, according to the government’s moderate estimates, Alberta will need almost 1,000 doctors, dentists and veterinarians; 3,077 carpenters and cabinetmakers; 5,432 cashiers; 2,007 bank and insurance workers; 3,917 mechanics—and that is just the beginning of the official worry list. Alberta is competing for workers with every western industrialized nation in an era of declining birth rates and retiring baby boomers. Skilled workers are finding new opportunities in their own nations. With elbows up, every province in Canada is struggling to bring the same immigrants to its corner of the map.

Alberta did not plan for managed growth when it approved the rapid expansion of the oil sands industry at a time of soaring oil prices. Begging for workers, the province’s employers want people in a hurry.

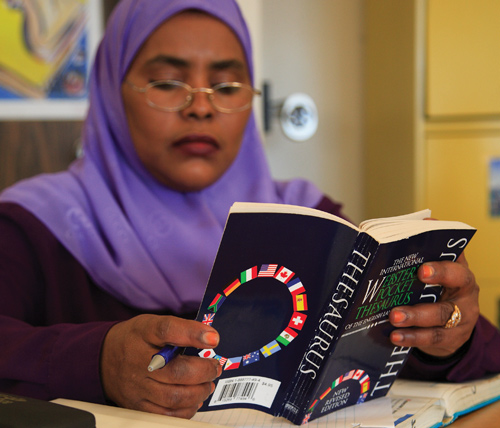

Marian Said is from Somalia, where she was a teacher. Now she studies English as a second language at Edmonton’s Norquest College. (Colin Smith)

Relatively few immigrants move directly to Alberta from other nations. Last year only 19,330 men, women and children—less than half the population of Grande Prairie—arrived in Alberta as newcomers from other countries. That was an encouraging increase of 3,000 in one year, but it still amounted to only 7.4 per cent of the total number of immigrants to Canada in 2005.

Secondary immigrants—those who land in other Canadian cities, then travel to Alberta to search for a better job—have been arriving here in significant numbers this year. How many? Nobody knows for certain. We do know that newcomers are spreading out unevenly. More than 9,300 people moved into Calgary from other nations in 2004, but Edmonton received only 4,810. Alberta’s smaller cities and towns are receiving a trickle. only 128 immigrants, including children, settled in fort McMurray in 2004, fewer than the number who settled in St. John’s, Newfoundland. Only 254 moved to Red Deer, 177 to Medicine Hat and 126 to Grande Prairie.

Fariborz Birjandian, the executive director of the Calgary Catholic Immigration Society, says the number of secondary immigrants to Calgary rose rapidly this year. “The word is out about our economy,” he says. Unfortunately, federal funding to assist new immigrants with education and training does not always follow them from Montreal, Toronto or Vancouver to Alberta. So far, provincial government funding for immigrant settlement agencies is inadequate to meet growing needs.

Coming from China, the Philippines, India or Pakistan— the top source countries for Alberta’s immigrants—families can spend up to $40,000 on moving and settlement alone, a fortune where they come from. They begin to hunt for a job that will produce enough income to support the family, and immediately confront Alberta’s housing and daycare shortage, unaffordable rents and rising house prices. Although 73 per cent of immigrants can speak English when they arrive here, the others can wait up to four months to find an English as a Second Language class. Many are perplexed and discouraged when they fail to find employment in a province where jobs are supposed to be plentiful.

“That is why we are losing quite a few of them over time,” says Birjandian. As chair of the Alberta Association of Immigrant Serving Agencies, he hears similar reports from colleagues in 20 organizations in eight communities. Cities and towns, schools and hospitals are struggling to assist a sudden influx of hopeful people. When newcomers are welcomed and assisted, says Birjandian, they thrive here. When they are unsuccessful and disheartened, they move away.

Alberta cannot afford their disillusionment. The province is already losing too many of its newcomers. Between 25 and 30 per cent of immigrants abandon the province after they’ve lived here for a time. In comparison, only 10 per cent leave Ontario or British Columbia after they arrive. Albertans are learning the hard way that immigrants do not always choose a new hometown for its red-hot economy or blue-sky bravado. They follow friends, relatives and the promise of a warm welcome. So what’s wrong? Something must explain why the city of Hamilton, Ontario, welcomed twice as many immigrants last year as all of Alberta outside Edmonton and Calgary; or why more foreigners moved to Winnipeg than to Edmonton in 2005.

What will it take to encourage more immigrants to come to Alberta, and stay put? Ask the experts in Room 701.

“Our Alberta government wants more people to come here, but the immigrants who are already here are suffering. Rich people are getting richer, but we others are getting poorer. Rent and food are so expensive here, and the minimum wage is low. For single mothers here, it is very difficult. If I could bring someone from my family to help me with the children, that would be good. I asked one time about this. They said for me to bring a nanny to Canada, I would need a higher income. I didn’t mean that. I could help a woman, a widow from home, who needed a place to live. We need some help with our children.”

—Anjlla Swamy

19 years in Canada, originally from Fiji

In October 2005, Alberta announced its first comprehensive immigration policy in an atmosphere of urgent self- interest. After huddling over demographic statistics for months, and consulting a diverse group of informed Albertans, senior government officials from four departments produced a detailed document, “Supporting Immigrants and Immigration to Alberta,” to prepare citizens for a change in direction. The Conservative government made four important promises: to make Alberta a more welcoming place for newcomers; to increase the number of immigrants; to expand programs and services that would integrate newcomers; and to help immigrants find better work opportunities. Each promise came with a checklist of intended improvements.

The plans were bold, specific and largely admirable. The government promised to be accountable with an annual report on progress. The new strategy surprised many professionals who work with immigrants, because it emphasized the newcomers’ contributions to the quality of life in Alberta, not just their capacity to serve as worker drones in Canada’s busiest beehive.

The hallways of Edmonton’s NorQuest College. (Colin Smith)

“My perception is that there was a very positive change,” says Justine Light, president of Alberta Teachers of English as a Second Language. “The government is doing a very good job with the money it has, and it is definitely more open to change than it was. The issue lies in the portion of the overall Alberta budget that goes to immigrants, and their needs.” Jim Gurnett, a former new Democrat MLA who has led the Edmonton Mennonite Centre for newcomers for a decade, agrees that the new strategy has all the right language. “I wish we could see movement faster on the real flesh of it.” If the plan is transformed into reality, Gurnett says, Alberta will move ahead of other provinces in its efforts to integrate new citizens. “Everything is there to do that. We need to see the action.”

So has there been any constructive action in the first year? Some.

“I am satisfied with the government because I have a dream to learn English. I feel very happy to live in Canada. I know some people from my country who are here. They don’t have a chance to learn English, so I feel very lucky.”

—LAI FONG

Four years in Canada, originally from China

True to its promise, the government of Alberta did increase its funding for immigration and settlement programs in the provincial budget last spring. It put an extra $3.5-million into ESL training to pay for 400 extra students, bringing the total number of students receiving support to 3,500. The government found another $1-million for settlement programs for a total of $3-million.

Alberta Human Resources & Employment—the department leading the immigration plan—received an extra $6-million to work on elements of the strategy. Finally the province added $1.2-million to expand “bridging programs” that provide foreign-trained professionals with Canadian work experience.

These small increases have had a positive impact, but they are hardly the sign of a dramatic change in direction. To put the numbers in context, Alberta is spending $48-million this year to lure international tourists to the province. Tourists don’t bring hammers and wrenches to join a construction crew in Lethbridge, or stay long enough to make an enduring contribution to Red Deer, but the tourism industry gets public dollars.

On the positive side, the province has acted decisively in the past year to help foreign-trained professionals who are underemployed in the province. foreign-trained pharmacists, for example, can now take advantage of a 35-week bridging program to prepare them for practical work and their licensing examinations. Similar innovative programs for engineers and accountants are proving very successful. Alberta is also permitting international students in colleges and universities to work here in the summer months, in the hope that they will decide to stay here after graduation.

Canada, not Alberta, is responsible for immigration, of course. The provincial government can’t dictate Ottawa’s settlement allocation funds for this booming western province, nor can it do anything about the backlog of 700,000 applications from prospective immigrants around the world who want to enter Canada but can’t get approval due to the clogged arteries in an ailing bureaucratic system.

That said, Alberta has stumbled in some of its recent efforts to increase immigration. Most provinces have signed provincial nominee programs with Ottawa to speed up the immigration process for skilled immigrants. Alberta has brought in just 300 workers since it signed the agreement in 2002; Manitoba brought in 3,499 workers through the same program because it pursued the opportunity more aggressively. Gurnett observes that the rush to bring hundreds of temporary foreign workers to the Fort McMurray oilfield camps might have been unnecessary if the nominee program for permanent immigrants had worked properly.

Alberta’s cities are trying to expand public services for immigrants on their own. “I think there is room for a great deal of improvement,” says Edmonton city councillor Michael Phair, who has been working with his colleagues on a strong immigration strategy for the capital. The best way to bring more newcomers to Alberta, he says, is to help the immigrants who came here from other provinces—if they feel welcome and integrated into city life, they will spread the good word to others.

Alberta’s recruitment campaign appears to focus on skilled trades workers, qualified technicians, professionals, entrepreneurs and affluent investors. Birjandian is concerned that the 2,250 people who came here last year as refugees need more help than they receive, especially the traumatized children.

Judy Sillito, an ESL educator in Alberta for 25 years, would like the province to do more to assist the newcomers who do not hold a favoured place in the labour market: children, adolescents, mothers at home raising families, and grandparents. “When compared to other provinces, Alberta’s commitment to education for newcomers is stellar,” she says. “However, the focus of this commitment is primarily geared to employment.”

Sillito sees an urgent need for new programs to help bright and able people with low literacy skills in their first language. The value of better education for these newcomers, she says, will prove itself in social rather than economic terms. “All need to find a place of meaningful participation in Alberta.”

“To make immigration to Canada more successful, the government should give more time for schooling for students who didn’t finish high school back home.

“I have been out of school for nine years. I just finished Grade 7. I had to stop because of the Taliban [which prohibited girls from attending school]. That’s why I did not finish high school. There are many like me.

“I came to Canada without English, not even one word. But I have a skill, I am a skilled tailor. For two months in the summer, I gave my application to sewing places all over the city, but I couldn’t find a job. I feel disappointed. I have to keep my spirits up. I will continue my education. I will never give up.”

—MOZGHAN BAKHSHI

Three years in Canada, originally from Afghanistan

Lena Bengtsson and Myra Mackay are also trying to keep their spirits up. They are immigration settlement counsellors in northern Alberta—and they are both struggling with severely limited resources to help a new wave of job seekers. “All of Alberta is going nuts,” says Bengtsson in Grande Prairie.

“We don’t have enough housing, we have a desperate daycare situation, and we don’t have enough ESL. I am working in a one-person office, and it’s impossible to do everything that needs to be done for people. I don’t want to lock the door, but I don’t know what to do… We can’t handle what we’re getting. Everybody keeps telling immigrants that we want more, more and more people. It’s crazy.”

Mackay agrees newcomers need to know about the reality of the Alberta boom economy before they arrive. “Immigrants get off the plane in Ontario, and they’re on the bus to Fort McMurray right away,” she says. Hundreds of foreign temporary workers in nearby camps are not eligible for federal settlement services, but many come to Mackay’s office looking for help anyway. “They are lonely, and they need information and an orientation to life here.” Mackay says the city urgently needs an expanded ESL program, interpretation and translation services and a host program to make newcomers feel welcome. “We need more staffing to help these people, too.” She works alone with a part-time assistant, waiting for funds to flow from promises.

“People had high hopes when they came here. My husband was a microbiologist, a professor in Somalia, who had worked on his PhD in Alabama. When the civil war happened at home, he couldn’t go back. He decided to come to Canada. He applied to many educational institutions, for many jobs. He tried to teach in a high school. They said he was overqualified. He worked in travel agencies, and as a security guard. They kept telling him he was overqualified, but other jobs were not available. This was not just happening to him. There are doctors, professors, teachers, engineers, all trying to find work. My husband was depressed, and I was worried…

“I say this to Canada: Don’t make empty promises. Why are you bringing people here if you are not going to hire them for jobs? That’s not logical. When you can’t take care of the people here—or hire us when we want to work—why are you bringing more people here?”

—MARIAN SAID

15 years in Canada, originally from Somalia

Skilled immigrants in Alberta say one of their greatest frustrations is the lack of recognition for their foreign credentials—their education, work experience and training. More than 48 per cent of newcomers to Alberta in 2004 arrived with a university degree; 5 per cent held a trade certificate and 11 per cent had a college diploma. The Alberta government has refused to force professional licensing bodies to improve their slow and expensive accreditation systems. Dr. Lucenia Ortiz, co-director of the Multicultural Health Brokers Co-op, says she has heard sympathetic rhetoric from the government and professional groups, but not enough impressive action.

In Room 701, the students are eager to discuss the problem.

“I will begin with a question,” says Germaine Bambi, a french-speaking immigrant from Congo. She turns toward me.

“You say you are a writer. You must have gone to university. What if you went to Congo tomorrow? How are you going to feel if they put you with all the people who never went to school at all?” She studied for two years in college, and worked as a social worker, before immigrating to Montreal, where she attended university. She moved to Alberta two years ago. “My husband and I put out 20 or more applications all over Edmonton. They never called us once. The only job we can find is cleaning. We can’t live on the money. Back home, in my country, many doctors decided to come here. They can’t find a job. Why can’t they just come here, and write the exams and go to work? The way they are treated is not fair.”

The students cannot fathom why Alberta licensing bodies can’t approve foreign credentials in a more timely, efficient way. “I would like to bring my brother here, but it is so difficult,” says Pono Mosenyegi, a former immigration officer from Botswana. “We do speak English back home, but I tell them: ‘If you come to Canada, expect to go back to school. They don’t respect your qualifications here.’”

Abdufetah Omer tells the class of his own frustrating efforts. “My career goal is to become a truck driver,” he explains. “Why is it so complicated for me to go through this process? I was told to go downtown to an office to get an application for more training. They made me fill out a lot of forms, and told me to go to another office. And it happened again. It became too much hassle for me. I gave it up, and found a summer job as a labourer.” He points out the window to the downtown traffic below. “Today I should not be here in this classroom. I should be working out there.”

The students wonder why they can’t find work. Are Albertans worried about job competition from newcomers? Do they dislike people from other countries? Answers are only guesses. The Canada West foundation reports that Albertans lead the nation in negative attitudes to immigration as expressed in public opinion polls. In one Angus Reid poll in 2000, 41 per cent of Alberta respondents said immigrants were “a drain on the economy.” That is a minority of Albertans, certainly, but a minority of employers can deliver a hostile message. Recent federal surveys suggest 17 per cent of job-seeking immigrants in Canada are still unemployed two years after their arrival.

Breaking a silence, Maria Garay, an immigrant from Argentina, brings up a possibility that others might be reluctant to mention. “I have been here for six years. I have seen much discrimination against other people. My case is different. The people here are not friendly enough. In many public buildings, and restaurants, immigrants are not treated right if they are people of colour.”

The room is quiet. Her classmates are nodding.

“We women who wear hijab get badly treated by other people. When we go out to a store, or to class, some people yell bad things to us. ‘You have rags on your head,’ they say. ‘Diaper head.’ They tell us to go back where we came from. I wish I could have better English to speak back to them. The way they look at us is scary. I don’t know why they feel this way. After September 11, it was way worse for us. We can’t be blamed. Even in Canada, all of you are not perfect. We can’t be blamed for what others did.”

—AMIRA BARAkAT

13 years in Canada, originally from Jordan

SERLINA TSANG has been waiting for her turn to speak. She left Hong Kong more than 20 years ago for Alberta. “I worked hard at two jobs during the day. My husband worked night shifts. I came here to Alberta, not for me, but for my children.”

She says her decision brought good results. She is the mother of an accountant, an engineer and a health inspector. She urges her classmates to pour their hopes into the next generation.

“I know this country tries to help,” she continues gently. “People expect more and more help, but this help comes from the income taxes of other people. You need to think about the Canadians who were born in Canada. They don’t get money to go to school. If you go to Malaysia or China, the government will not give you one penny. Canada is the best country for benefits to the people.”

She looks around the class, and waits for a reply.

“I need to say something,” says Marian Said. Her voice is firm, but not angry.

“I came to Canada in 1991, sponsored by my husband. I never went to the government. I taught myself English. I worked all day in a factory packing airline food for $6 an hour. My husband worked all night as a security guard. We got laid off, each of us. I do believe in supporting myself. I was a teacher in Somalia. I believe in education. When my husband was laid off, I said, ‘Should we go to welfare?’ My husband looked at me like I was a stranger. He said: ‘I would rather be homeless than do that.’”

She pauses,then continues.“African women work the hardest of any in the world. We can walk 10 miles to fetch water. If you have dignity, you cannot depend on others. I know that. I am not blaming the government of Canada, or Canadians. I am blaming their policy. They need to open the door. The door is shut to us.”

Linda Goyette is collecting stories from newcomers to Alberta for an anthology called The Story That Brought Me Here