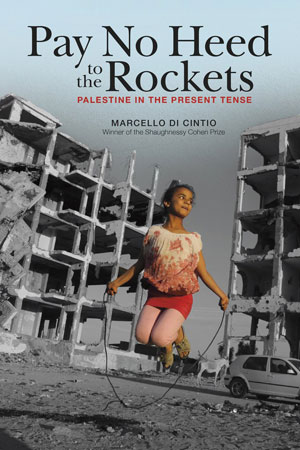

The narratives of places shattered by war are often told lopsidedly—stories of violence and destruction become the focus, while the people themselves, their daily lives, losses and joys, their need to look toward a productive future as much as to acknowledge a damaging past, are relegated to the background. Marcello Di Cintio recognizes this danger in the early pages of his latest book, Pay No Heed to the Rockets: Palestine in the Present Tense. During the research and writing, Di Cintio came to understand he did not want to see Palestine as “an enduring and unsolvable political problem but as something physical that exists in the present tense. And [he] wanted to see Palestinians as a people unto themselves, not merely as one half of a warring binary. Not in opposition, but in situ.”

Di Cintio is not new to writing about places in conflict. The author of three prior books of non-fiction, he is best recognized for 2012’s Walls: Travels Along the Barricades, an exploration of the most disputed areas in the world and the boundaries that divide them. In this earlier text, Di Cintio also pairs narratives of conflict with narratives of the people behind the lines. It’s his attentiveness to those within the conflict, his constant striving to represent them as they are rather than simply as subjects of violence, that makes his writing so rich.

Grounded in this need for a more nuanced focus in his recounting of controversial modern-day Palestine, Di Cintio opens Pay No Heed to the Rockets on the Allenby Bridge crossing—the only entry/exit point for West Bank Palestinians—at the start of a journey that will take him into the lives and literature of the people of Palestine in a search for beauty; for what has been left out of so many earlier accountings. “Nothing is more beautiful than a story,” he notes, “[a]nd nothing is more human. To weave the snarled strands of a life, either real or imagined, into literature is a form of blessed alchemy.”

Di Cintio grounds his exploration of Palestine in the words of its writers, acknowledging icons such as Mahmoud Darwish and Ghassan Kanafani, but turning also to new writers and their struggle to create space for their work beyond the long shadow of those who came before and the gender and political conflicts that inform their lives. Along the way he is invited into open conversation but also encounters suspicion about the foreign writers now thronging to Palestine who stayed at a safe remove during the worst of the violence. He’s forced to confront his own tendency to look for the tragic, to see Palestinians as either participants in violence or as victims. Di Cintio’s two journeys, into the heart of Palestine via its writers, and into his own ingrained ways of seeing, make for a deeply engaging read.

—Jenna Butler has written five books of poetry and non-fiction.