The jury of seven military officers is filed back into the courtroom in Guantánamo Bay at the end of eight long hours deliberating the fate of Omar Khadr. Sitting next to Khadr, watching tensely, were two Edmonton lawyers, Nate Whitling and Dennis Edney. For the past seven years, the two Albertans had waged a determined battle for legal rights for Khadr. They had been to the Supreme Court twice, with some success, in their effort to bring the rule of law to bear on the case. They’d travelled a dozen times since June 2007 to visit their client at this notorious US military prison and to help his American military lawyer, Lt. Col. Jon Jackson, prepare the defence. This day, October 31, 2010, was a critical point in their journey—the fate of their client would finally be decided.

“Make no mistake, the world is watching,” the military prosecutor told the jury. “Your sentence will send a message.” Indeed. The court had accepted Khadr’s guilty plea (part of a plea bargain) the week before. Today it would recommend a sentence—and signal the kind of justice to be had from the contentious and deeply flawed US military justice system.

Whitling and Edney knew the legal deck was stacked against their client in the military commission system, which violated the rule of law and other fundamental principles of justice. For instance, in the military court, evidence obtained under torture was admissible—unthinkable in regular courts. The prosecution was not required to disclose its evidence, as required in regular courts. The military commission system, devised post 9/11 and modified by the Obama administration, was so stacked against the accused that the US government ruled its own citizens could not be sent to trial there. This was justice suitable for foreigners only.

But the US government was not the only one to ignore its own traditions concerning the rule of law. Months before the trial, the Canadian government ignored the recommendation of its own courts, which ruled Khadr’s Charter rights had been violated when Canadian security officials participated in illegal interrogations of Khadr. To remedy that wrong, the government should bring Khadr home, the courts said. Instead, the Harper government played to the politics of the day by leaving him in Guantánamo, argues Edney. By failing to uphold the rights of one citizen, he adds—however unpopular the citizen—the government undermined the legal rights that protect all Canadians.

The defence of Omar, second youngest son of Canada’s notorious al Qaeda-linked Khadr family, was not a popular cause. The family’s ties to terrorist Osama bin Laden were a shocking betrayal of national values and an affront to Canadians. For Whitling and Edney, however, a greater principle was at stake: the rule of law, so fundamental to democracy. Every Canadian citizen is entitled to the right to counsel, protection from torture and to a fair trial. Khadr had none of that in Guantánamo.

The two lawyers are, as Edney likes to say, “as different as chalk and cheese.” Whitling, mid-30s, bookish and reserved, is a brilliant legal mind. Raised in a middle-class Edmonton home, Whitling went on to become the gold medallist in his University of Alberta law class. From there, he studied at Harvard, clerked at the Supreme Court of Canada under Justice John Major, then joined one of Edmonton’s biggest downtown firms, Parlee McLaws.

Edney, 20 years older, a veteran criminal lawyer in a small Edmonton office, was a professional soccer player in Scotland before he went to law school. Behind his charming smile is a pugnacious, stubborn streak. He says it comes from his Scottish upbringing, which taught him to stand up for his rights or “be downtrodden.” The notion of challenging the powers that be comes naturally to him. He also learned in his family a deep distaste for prejudice. His parents were a rare Catholic/Protestant marriage during the Second World War, much frowned upon by both sets of in-laws. To this day, the Catholic side won’t let his mother’s ashes be buried with his father, says Edney, shaking his head.

In late 2002, Edney and Whitling joined forces to take on Khadr’s case. The 15-year-old, captured in Afghanistan, was moved to Guantánamo, where he was held for years with no charges, no right to habeas corpus (to challenge his detention) and no access to lawyers. Whitling and Edney, who work pro bono on this case, figured their best strategy was to see if Canadian courts could force the government to insist on fair treatment for Khadr. The question: under the Charter of Rights, what are Canada’s obligations to one of its citizens detained in a foreign legal system that does not provide basic rights?

In the post-9/11 era, the Khadr case tested the balance between the need for security in the West’s “war on terror” and the need to uphold Canada’s long-standing civil liberties. The US put Guantánamo deliberately offshore to exempt it from the US constitution and its legal protections. Could Canadian officials also turn a blind eye to the fact Khadr was denied those normal legal rights, and that he was a juvenile as well?

The case also tested Canada’s commitment to its international obligations. Canada has signed both the UN protocol on child soldiers (which states that child soldiers should be rehabilitated, not sent to trial) and the UN convention against torture. Canada sends funds to help rehabilitate child soldiers in Sierra Leone. But the federal government made no effort to protest when the US put Khadr on trial in an adult court for crimes committed when he was 15 years old. Human rights groups and many ordinary Canadians decried this as a sign Canada was backing away from its commitments to international law. While all other western countries got their citizens out of Guantánamo, mainly because they found repugnant its lack of legal protections, Liberal and Conservative governments in Canada left Khadr there to face whatever the US military had in store.

Whitling flipped open a newspaper one morning in February 2003 and found the grounds for the first battle. An article reported that Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) agents had gone to Guantánamo and interrogated Khadr about his role in the killing of US soldier Christopher Speer in a battle in Afghanistan. At the time of those interrogations, Khadr was being detained with no charges and no right to a hearing. Whitling thought a pretty good argument could be made that Canadian officials could not go to another country and participate in detentions that would be illegal at home. The two lawyers wanted to stop the interrogations and force the government instead to start consular visits to check on the welfare of the prisoner. They won on both counts.

On August 8, 2005, the Federal Court upheld their case and handed down an injunction against further CSIS interrogations, citing Guantánamo’s lack of legal protections. “Detention conditions, interrogation techniques used and rules of evidence employed at the US Combatant Status Review Tribunal do not comply with Charter standards,” wrote Justice Konrad von Finckenstein.

“One of the best things we did was put an end to those interrogations,” recalls Whitling. The reason why became clear in their next case, dubbed Supreme Court One, which was about the right to disclosure. The case revealed the shocking treatment of Khadr before those interrogations. During the first trial, CSIS officials admitted to handing over the results of their 2003–2004 interrogations to the US military as evidence against Khadr. Canadian officials, in other words, were helping build the case against Khadr. Under the Canadian Charter, the accused has the right to see all the evidence against him. So Khadr’s Edmonton lawyers decided to push for full disclosure of the interrogations—documents and videos—in accordance with the principles of fundamental justice.

Every citizen has the right to counsel, protection from torture and a fair trial. Khadr had none of that in Guantánamo.

The Federal Court denied disclosure, on national security grounds. But the Federal Court of Appeal upheld their case and ordered the documents released. The federal government appealed to the Supreme Court of Canada in an effort to keep the documents secret.

On May 23, 2008, the Supreme Court ruled in Khadr’s favour. Canadian officials had violated international laws when they interrogated Khadr knowing he had been subject to cruel treatment that violated human rights. A number of the documents were released.

In the end, the two lawyers got access to only about 14 pages of many thousands. But these were enough. The documents revealed that Canadian intelligence officers had been told directly in 2004 that Khadr was subject to severe sleep deprivation—moved every three hours for three weeks in what was known as the “frequent flyer program”—to soften him up for Canadian interrogators. Canadian officials went ahead with their interrogations anyway, knowing Khadr had been subject to techniques deemed “cruel and degrading” under new US torture memos but simply called “torture” in many jurisdictions.

To this day, Whitling is still shocked by that revelation, given that the Liberal government told the public it had accepted US assurances of no ill treatment. ”What we will do is what we have done so far, which is, at the end of the day, the US will proceed as they see fit,” said Edmonton-area MP Anne McLellan, minister of public safety in February 2005. “We have sought assurances that he is not being ill treated and those assurances have been given by the US.” Yet officials in her department had clearly known different.

Edney and Whitling moved on to the next step. If Canadian officials had violated Khadr’s rights, there had to be a remedy. They asked the Federal Court to order repatriation of Khadr. This legal battle would prove to be far more complicated—and the outcome much more of a political proposition—than they’d imagined.

The two lawyers now prepared to take on the Harper government in the highest court in the land—not a job for the faint of heart. In November 2008, the two lawyers prepared Supreme Court Two: Khadr v. Canada (Prime Minister). They won the first two rounds: the Federal Court and its appeal division both ruled that Khadr’s Charter rights had been violated when Canadian officials participated in interrogations knowing about the torture and knowing no charges had been laid. To remedy the rights violation, the Canadian government must apply for repatriation, the lower courts ordered. “While Canada may have preferred to stand by and let the proceedings against Mr. Khadr in the US run their course, the violation of his Charter rights by Canadian officials has removed that option,” wrote the appeal court.

Citizen advocacy and legal groups began to pressure the Canadian government to bring Khadr home. Amnesty International, UNICEF and the Canadian Bar Association called for action. But the Supreme Court in January 2010 wouldn’t go that far. It agreed that Khadr’s Charter rights to life, liberty and security of person were violated when “Canadian officials questioned [him] … in circumstances where they knew that Mr. Khadr was being indefinitely detained, was a young person and was alone during the interrogations…”. While this represented another victory for Whitling and Edney, it also marked the end of the winning streak. The Supreme Court, rather than order the government to seek the repatriation of Omar Khadr as the lower courts had done, declared it would defer to the government to decide on a remedy “in light of its responsibility over foreign affairs.”

The Harper government declined to repatriate Khadr and instead proposed a different remedy. It asked the US military not to use the information obtained in the interrogations by Canadians in its subsequent trial of Khadr. The US military declined the request. Under the rules of the military commission, evidence obtained under duress would be just fine in court.

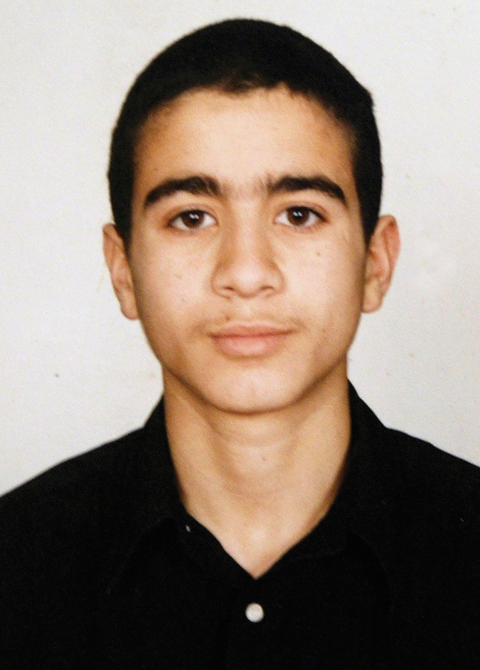

Omar Khadr at the age of 14. (Photo Courtesy of Khadr Family)

The Supreme Court decision in the Khadr case sparked a major controversy in Canadian legal circles. Human rights advocates said the judgment weakened the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Rights violations with no remedy undermine the rule of law. Others said the court found the right balance in its decision and wisely avoided a showdown with the Canadian government, or the US government for that matter.

Edney points out that to this day there has been no remedy for the violation of Khadr’s Charter rights. That’s deeply troubling, he says. After the US government rejected Harper’s alternative, the federal government took no further action. By failing to come up with another remedy, the Harper government put itself above the law, Edney says. “By not taking that step, I feel it puts us all at risk. This government is saying it is above the law.” (That legal battle is not over, he adds.)

Whitling notes that he is obviously disappointed the court did not order repatriation. But in the end, he says, the question of Khadr’s repatriation really came down to politics.

Back in the Guantánamo courtroom, only two witnesses were called to speak on Omar Khadr’s behalf at the sentencing hearing. One was a US military officer, Captain Patrick McCarthy, a senior legal adviser at Guantánamo between 2006 and 2008 who saw Khadr regularly. He told the court he believed Khadr was not radicalized and could be rehabilitated. “Fifteen-year-olds should not be held to the same standard of accountability as adults,” he told the jury.

The only other defence witness—and the only Canadian to give evidence—was an articulate, courageous English professor from a small Christian college in Edmonton, Arlette Zinck. She revealed that for two years she had quietly corresponded with Khadr, sending lesson plans in letters smuggled past military censors (see sidebar, p. 39). She told the court that the person she came to know through their correspondence was a polite, well-read young man making progress with his studies—even though his formal education ended at Grade 8. Their letters—Khadr’s handwritten in juvenile script—were entered in evidence and later published by the Edmonton Journal.

Edney and Whitling recognized, however, that McCarthy’s and Zinck’s evidence wouldn’t amount to much given that the US military had allowed evidence obtained under torture. Under the plea bargain, Khadr pleaded guilty to murdering Speer and to four other charges: spying, attempted murder, conspiracy and providing material support for terrorism. He agreed with an eight-page statement that called him, as an “alien unprivileged enemy belligerent,” fully cognizant of his actions. In exchange for his guilty plea, Khadr would be incarcerated for one year in solitary confinement at Guantánamo, then transferred to Canada for the remainder of his sentence.

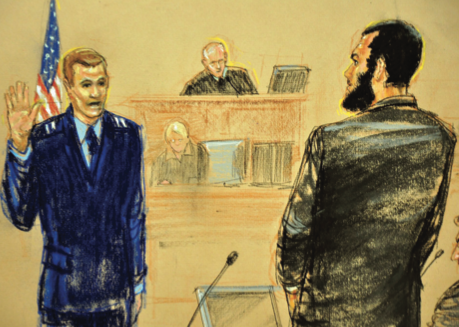

Captain Michael Grant, United States Air Force, swears in the now 23-year-old Khadr during his trial. (CP Photo/Janet Hamlin)

The jury, as it filed in on that October day, was unaware that the plea bargain set a sentence of eight years. If the jury recommended a lower sentence, it would apply. But a higher sentence would be largely symbolic. As Khadr’s was the first trial held under the military commission system—and as he was the last Western citizen remaining in Guantánamo—the world was paying close attention to see what kind of sentence, what kind of justice, would be given.

Whitling and Edney hoped the jury would recommend a lower sentence. The prosecution wanted the sentence increased to 25 years. The jury weighed two views of Khadr. Was he an unrepentant terrorist, radicalized and dangerous? Or was he, as the defence maintained, a teenager pushed into battle by his father and now a compliant prisoner committed to his studies and deserving of a second chance?

What came next was a jolt, says Whitling. The jury took their seats and announced their decision: a sentence of 40 years. It’s highly unusual, in regular courts, for a sentence higher than even what the prosecution calls for. But then, this wasn’t a regular court. “We were all shocked,” said Whitling. “It just underscored the unfairness of the system.”

By not coming up with a remedy, the government is putting us all at risk. It’s saying it is above the law.

As he looked over at Khadr in that dramatic moment, Edney recalled thinking: “Thank God we’d done the plea bargain deal. Otherwise Omar would be there for the rest of his life. Without that, I’d be picking him up at 64 years old.”

After an eight-year legal battle, Dennis Edney says that Canada’s courts did an excellent job upholding Khadr’s legal rights and the rule of law, ruling the government out of order when it violated those rights. The trouble came from a government that refused in the end to uphold Khadr’s rights. What’s troubling, says Edney, is that a legal black hole like Guantánamo undermines respect for the rule of law. People begin to think the rule of law applies only to “good people. That’s fatal for a justice system. Everyone deserves a fair trial.”

Edney also suggests that the Canadian public was complacent. “I wish more people had stood up for this,” he says. If a democracy does not protect the legal rights of its least desirable citizens, he notes, no citizen can be sure they’ll have those protections when they need them.

“I may have lost faith in the government for failing to do the right thing, for acting on their own self-serving motives,” Edney concludes. “But I haven’t lost faith in the judicial system.”

In early February 2011, Nate Whitling travelled back to Guantánamo to visit Khadr. The two spent half a day going over his schoolwork. But the main purpose of the visit was to prepare the application to transfer Khadr to a Canadian prison as the plea bargain stipulates.

“It’s our job to be cautious,” says Whitling. “But given that Canada’s promise was made not only to Omar but also to the US government, we do not anticipate the government will go back on its word.” #

Sheila Pratt is a senior feature writer at the Edmonton Journal and co-author of Running on Empty: Alberta after the Boom.