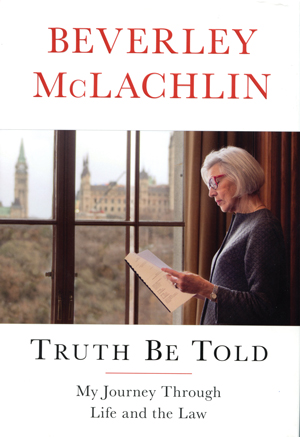

by Beverley McLachlin

Simon & Schuster

2019/$39.99/384 pp.

Beverley McLachlin’s memoir Truth Be Told chronicles her rise from “just a small-town girl from Pincher Creek” through the male-dominated ranks of Canadian lawyers and judges to become the first female chief justice of the Supreme Court of Canada. After her first judicial appointment, in 1981, it took only eight years to advance through four more appointments and become one of nine justices on the Supreme Court. As one wag noted at her 1989 swearing-in ceremony, “She made it through the court system faster than most cases.” Eleven years after that she was appointed chief justice.

As with all success-story memoirists, McLachlin must walk the fine line of explaining her impressive achievements while also portraying herself as a regular, down-to-earth person and a reliable narrator. She accomplishes this by not assuming that every reader will understand the Canadian court system, but also by never judge-splaining minutiae. In one sense the book acts as a primer: how judges get their jobs, what’s expected of them and how the best of the best approach judicial tasks.

McLachlin distills multifarious facts into a smooth, linear narrative—a skill likely honed over decades of writing legal decisions, and very welcome in a memoir. The dialogue clunks in places, but this quibble does not detract from the many strong scenes and the bright, clear prose.

During McLachlin’s time on the Supreme Court, landmark decisions were made that impact freedom of expression, assisted suicide, equal protection and benefits for LGBTQ people, Quebec separation and the rights of Indigenous people to use oral evidence in court to establish title by showing historical use of specific lands. The Charter underpins these decisions.

Truth Be Told is also a personal reflection that follows her childhood, first marriage, life as a young mother and, after her first husband dies, a period of time as a single mother who also happens to be head of the highest court in the country. McLachlin worries, falls in love and has periods of self-doubt, work overload and stress. She is like most of us, except smarter.

McLachlin does not dwell on the sexism she experienced. But those challenges are the backbone of this memoir. McLachlin writes, “And ever resurfacing, even in retirement, is the issue that I have been struggling with through the lengthening course of my professional life: Why is it harder for women than men to make their way in the world… the old gender stereotypes continue to rear their heads.”

McLachlin retired in 2017. To her barrier-crushing credit and for the betterment of Canada, she is the longest-serving Chief Justice in Canadian history. It’s memoir-worthy material.

—Barb Howard is a writer and former lawyer in Calgary.