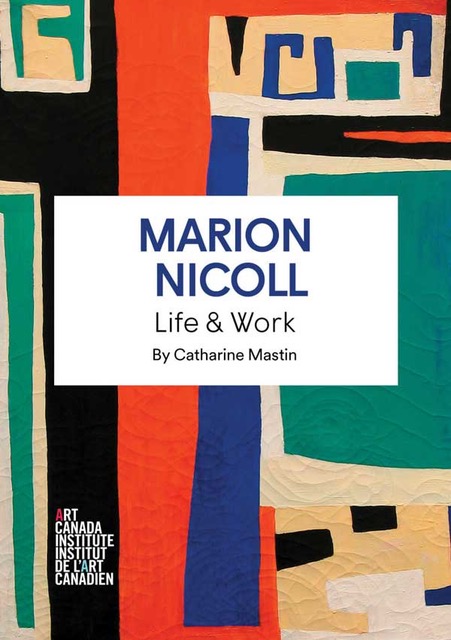

Catharine Mastin’s new e-book on the innovative and influential Alberta artist Marion Nicoll (1909–1985) is a must-read and must-look. Published by the Art Canada Institute, Marion Nicoll: Life & Work contains judiciously curated images of Nicoll’s art, alongside Mastin’s superb evaluation of her work within the context of 20th century art history in Calgary, Canada and internationally. Where relevant, Mastin brilliantly compares Nicoll’s art with the art of Kandinsky, Rothko, Hofmann, Jock Macdonald and Joyce Wieland.

We learn about Nicoll’s transformation from naturalism, to her secretly practising automatics (where the subconscious and chance play a role) thanks to Jock Macdonald’s teachings, to her full-fledged embracement and pursuit of abstraction—“hard-edge painting” of flat, coloured shapes. Along the way, Nicoll withstood Calgary’s and Alberta’s patriarchal arts society. She was the first woman from the prairies to become a member of the Royal Canadian Academy and was the first female instructor at the Provincial Institute of Technology and Art (now split into SAIT and Alberta University of the Arts), where she taught crafts for 25 years. Responding creatively to Alberta’s qualities of weather and nature, Nicoll’s large body of work features profound paintings and prints including woodcuts and collographs, batiks with aniline dyes, jewellery and public art.

Mastin’s intimate and extensive knowledge of Nicoll’s art stems from her time as senior art curator at the Glenbow Museum from 1995 to 2006, and her Ph.D. thesis on artist-couples in Canadian art for the University of Alberta. This is a fabulous, comprehensive book. However, Mastin mixes up Will Barnet, Nicoll’s teacher in New York, with Barnett Newman. In her Interim Report to the Canada Council, dated June 6, 1959, Nicoll wrote: “Mr. Barnet was most encouraging to the extent of urging me to move to New York.” Not New York artist Barnett Newman, as Mastin states on page 14. In her discussion of Barnet’s Emma Lake workshop in 1957, Mastin does not reveal how Barnet set up his model “and then extending it with colour pieces… so that your eye expanded away from the figure” (Nicoll). Students would see beyond the figure, flatten it and abstract the entire view. Crucially, this experience led to Nicoll’s first abstract, a watercolour, Little Indian Girl 1957–58. Mastin simply describes this process as “distill and simplify the sights seen through inner imagination” and “third, paint these forms.” Mastin also does not mention Illingworth (Buck) Kerr, Nicoll’s art college boss, as an adversary she had to deal with.

Nevertheless, Mastin has provided an engaging, much-needed portal to learn about a great Alberta artist, Marion Nicoll.

Nancy Townshend is an art curator and author in Calgary.

_______________________________________