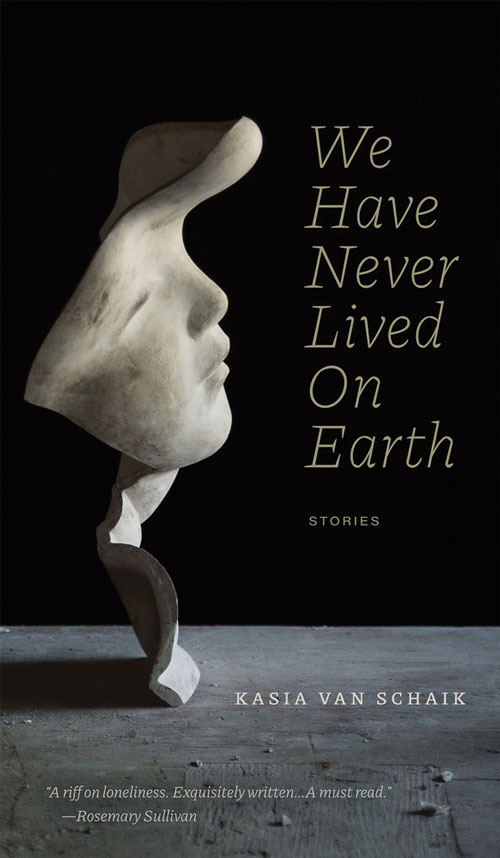

Kasia Van Schaik’s fiction debut, We Have Never Lived On Earth, is a collection of linked short stories that trace the life of a young woman, Charlotte, from an unconventional childhood in small-town BC through searching stays in cities across Canada and Europe and her returns home. Poetic and fragmented, surreal and allusive more than narratively linear or psychologically explanatory, the collection is permeated by nostalgia, disconnection and longing.

This longing is often articulated through precise, memorable imagery; sometimes it lands and other times it seems divorced from dramatic context. In “A Girl Called Helsinki,” Charlotte learns about childhood acquaintance Miranda’s strange stay in Budapest; near the conclusion, we get a striking picture of ducks floating on steaming thermal waters as skaters circle a frozen river nearby, with Miranda kneeling “beside the water, testing it, needing proof of this miracle of contrasts, of the rare geological events taking place below her.” Yet we haven’t been made to care about the character sufficiently for these lines to hit us with full emotional weight. In “Visitor to Crete,” the allusions are nearly in freefall—the labyrinth motif, the eyes of strangers, lost or sunken cities—all these beg for interpretation but are too loosely connected for the compelling details to make an equally compelling whole.

In other stories poetic force does line up with dramatic tension and the effects are extraordinary. In “How to be Silent in German,” Charlotte and Lukas spend weekends by a lake, where one day a woman is drowned by a man. When Charlotte stops trusting men and sees the plan “to eradicate women from the earth” in both men on the street and in Lukas, “a kind of cruelty in his voice,” the reader is fully convinced. The final lines—when Charlotte visits him years after their breakup and she and Lukas disagree about whether the man at the lake was a stranger or a boyfriend—are so perfectly rendered that one knows this is an author fully in control of her material.

“The Cascades,” similarly but more loosely, connects ordinary interaction with the violence of the École Polytechnique massacre, and the result is chillingly convincing. “Cellular Memory” asks what remains in our bodies of people from our past; the narrator spends most of her waking hours sleeping in her sister’s spare room, recovering from heartbreak, dreaming of icebergs “encased in their own silent misery.” The reader knows this is not depression but a grief for all things continually lost.

This is a unique collection, worth reading for its emotional depth and beauty of language, and for the introduction it forms to a fresh, smart new voice.

Jasmina Odor is the author of You Can’t Stay Here

_______________________________________