The month after Chris Crane’s 18th birthday was a blur. The Alberta Warriors gang member spent most of it drunk or stoned, blowing $16,000 on alcohol and marijuana in just three weeks. His first month of official adulthood ended with an armed robbery, a drive-by shooting at a house frequented by rival gang members, and his arrest.

His errant gunshot, which struck a two-year-old girl in the chest as she was sitting at her grandparent’s kitchen table, galvanized the Samson Cree First Nation near Hobbema. The child survived, but the shooting was the last straw for members of the community of 12,000 and they came out swinging with plans to eradicate the 13 gangs that terrorized them. The court, keenly aware of the public indignation, sentenced Crane to nine years, reduced on appeal to seven.

But the April 13, 2008, shooting of Asia Saddleback set off alarms around the province and heightened public interest in reining in the gangs that had become more numerous, overt and violent during the Alberta boom. A triple slaying that included an innocent bystander at a southeast Calgary Vietnamese restaurant eight months later served notice that gang violence wasn’t just an Aboriginal community phenomenon. A war between two Calgary gangs, Fresh off the Boat (FOB) and the Fresh off the Boat Killers (FK) had claimed 25 lives since 2002. But the January 1, 2009, slaying of 43-year-old contractor Keni Su’a triggered outrage. It wasn’t just gang members killing gang members anymore. The public wanted something done. Following an investigation involving more than 600 police and civilians, four men were charged with first-degree murder.

“That particular shooting sent shock waves through the community,” says Calgary Police targeted enforcement unit detective Gordon Eiriksson. “When an innocent bystander gets shot and killed, it really galvanizes us as a police service.”

The triple slaying capped off years of killings, shootings, stabbings and beatings by members of a gang that had fallen out of sorts, split into factions and begun trying to eliminate each other. The deaths, deportations, prison sentences and charges against key members on both sides have brought some respite, but Calgary police aren’t counting on lasting peace.

What draws a kid to a gang? Not just the money, but the brotherhood. For many gang members, it’s the first time anyone has cared about them. “With the clients I represent who have gang affiliations, the common thread is a lack of a role model and support at home,” says Edmonton lawyer Harold Brubaker, who represented Crane at his 2010 trial. “The function the gang ends up playing, for better or worse, is to give them a sense of identity and belonging.”

Crane’s own testimony at his sentencing in Wetaskiwin suggested he grew up without a father and was shuffled back and forth between relatives from the age of 3. “I was allowed to do whatever I wanted as a kid,” he testified after pleading guilty to charges of aggravated assault, weapons charges and a home invasion robbery. “It seemed to me like nobody cared.”

By age 11, Crane was smoking marijuana daily. By Grade 7, he’d stopped attending school. A psychologist hired by the defence described him as a severely traumatized, sad and tormented child who became a moody, hot-tempered, bitter and violent teen. He said Crane was sexually abused as a child and suffered from anxiety and depression.

Although the heavily tattooed Crane told the court he wanted to leave gang life to focus on his wife and child, gangster rap lyrics and drawings were found in his remand centre cell. A hand-drawn sign found with his belongings proclaimed: Thug life until the end of time.

Aboriginal gang members are often distinguishable by tattoos and colours and are territorial, frequenting certain areas of specific communities. While they may be among the most visible gangs, they are not the major focus of Alberta police. The province’s law enforcement agencies are more interested in the criminal organizations that control the bulk of the drug trade in the province. They also focus on violent gangs engaged in open warfare on city streets.

What draws kids to gangs? A sense of identity. “The common thread is a lack of a role model and support.”

More than 900 gangs operate in Canada, according to police intelligence, and 83 of them operate in Alberta—up from 54 in 2008. (According to the Alberta government, “gangs” include criminal organizations, or “groups of two or more individuals” who conspire within an ongoing network to break the law, and street gangs, defined as “more or less structured groups of adolescents and young adults” who use intimidation and violence to commit criminal acts.) Gang expert Cathy Prowse, a University of Calgary criminologist and former Calgary police officer, says the top criminal organizations have fixed, close-knit memberships, are largely invisible and handle most of the importation and distribution of drugs in Alberta. “The street gangs are one rung below and will always rival one another for affiliation with organized crime,” she explains. “There are only a fixed number of spots. The shooting starts with peripheral associates, each group hoping to destabilize the other. Violence is the way to preferential affiliation.”

Edmonton criminologist Bill Pitt says the Hells Angels still rule the roost in Canadian organized crime while street level gangs fight over the crumbs. For the most part, they fly under local enforcement radar. “There are so many layers of retailers before you get to the Hells Angels and the other biker gangs,” says Pitt, who teaches at Grant MacEwan University.

Many ethnic gangs still exist—Indo-Canadian, Asian, Jamaican, Somalian. Pitt says these are a product of Canadian immigration policy. “Canadians are notorious for marginalizing their immigrants,” he contends. And while Aboriginal gangs are prolific in Western Canada, “they’re at the lower end of the food chain when it comes to sophistication.”

In Edmonton the police gang unit has files on about 50 different groups. “We have 15 to 20 groups we keep track of, who’s associated with them and a bit of their hierarchy, but I’m sure there are a lot we don’t know about,” says Staff Sergeant Darren Derko, who directs the 35-member gang unit out of a small, second-floor office at Edmonton’s downtown police headquarters. In 2007, the unit released the names of 10 street gangs active in the city. The list included, along with the Hells Angels, the Alberta Warriors, the Crazy Dragons, the Crazy Dragon Killers, GTC (Get the Cash), Indian Posse, North End Jamaicans, Redd Alert, Southside Boys, West End Jamaicans and White Boy Posse.

Police in Alberta are reluctant to disclose a list of the gangs in their jurisdiction, and the Calgary Police Service’s Eiriksson won’t even refer to the “criminal organizations” by name, because he doesn’t want to give them credibility in the eyes of Calgary’s youth. “When they’re in our streets killing each other and shooting innocent people, we don’t give them any validation.”

Derko says it’s getting more difficult to tell who’s who because many of the people they arrest don’t identify as belonging to a gang. “They don’t give themselves distinctive names anymore,” says Derko. One explanation may be a federal law that now makes it illegal to belong to a criminal organization. But probably the biggest reason, say police, is that gangs no longer want notoriety. “The groups we deal with are low-key because they don’t want us to know who they are, who they associate with and what activities they’re involved in,” says Eiriksson. “They quite often blend right in and thrive on that anonymity.”

Gang-related homicides are difficult to solve because gang members don’t co-operate with police, and witnesses are often afraid or unwilling to come forward. This came to a head in Edmonton in January when a homicide detective berated the Somali community for not co-operating with police investigating a fatal New Year’s Eve shooting of a Somali youth at a club. The city’s acting police chief apologized to angry community leaders, and vowed to keep detectives working on the unsolved homicides of more than 30 young Somali men in Alberta in the past five years. The low “clearance rate” is not unusual. Out of 77 gang homicides committed in Alberta between 2002 and 2006, more than 60 per cent remain unsolved, according to a 2009 report by the Calgary Police Service. The national clearance rate for gang crimes in 2006 was only 45 per cent, compared to 80 per cent for non-gang killings.

Police say Edmonton and Calgary had the second- and third- highest gang homicide rates in Canada in 2006 and 2007. The cities dropped to seventh and ninth respectively in 2009 when total Alberta gang homicides dropped to 13 (from 35 in 2008), but even then one in five homicides was gang-related.

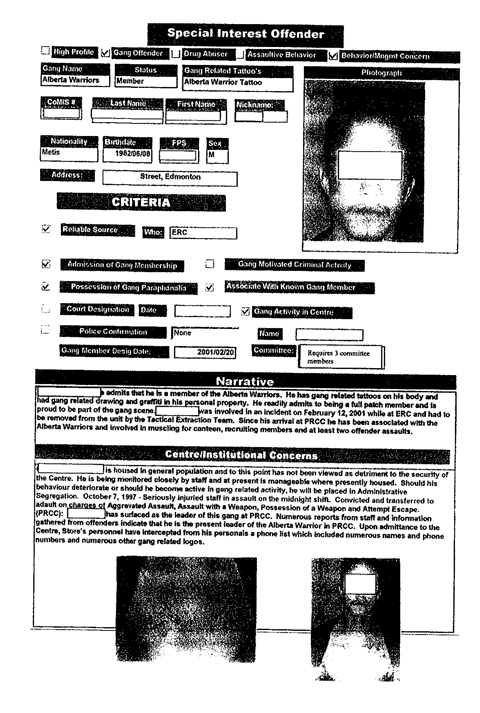

A government profile of the alleged leader of the Alberta Warriors at the Peace River Correctional Centre.

While the visible cost of gangs can be tabulated by counting coffins, the economic and social costs are incalculably high. The cost of policing, courts and incarceration is likely trivial compared to the damage done through the sale of illegal drugs—particularly healthcare costs—lost productivity, financial support for abandoned children and dysfunctional families. The U of C’s Prowse says no one has a handle on the cost of mortgage and insurance frauds and credit card scams related to gangs, but the numbers are likely huge. Then there are the psychological costs stemming from intimidation and a culture of fear in communities. “The obvious risk to the public is when these guys decide it’s time to take out a rival,”

Prowse says.

The government says gangs flourish in a community of indifference. “Too many individuals believe gangs are ‘not my problem’ or that gang crime happens ‘somewhere else,’ ” the province announced in a November 2010 report called “Alberta Gang Reduction Strategy.”

Government and police have recently taken initiatives to improve the way they tackle organized crime, including a major restructuring of the law enforcement machinery. The first changes occurred in 1996 when the province formed an independent body called the Criminal Intelligence Service of Alberta (CISA) to collect data on criminal organizations and provide it to municipal police agencies, Canadian Border Services, gaming and liquor officials and federal and provincial corrections agencies. “Before, there wasn’t a clear understanding of what organized crime looked like in the province,” says CISA director David Maze. “There was a need for an agency to look outside its own backyard and get a better understanding of the criminal element across the province.”

In 2006, the province established another independent enforcement initiative, called Alberta Law Enforcement Response Teams (ALERT), complete with its own civilian board of directors, to take action based on intelligence gathered on organized crime groups and other serious criminals such as child abusers, sexual predators and fugitives. With escalating gang violence in Calgary and Edmonton, ALERT was expanded in 2009 to nearly 400 people, most of whom—more than 300—were funded from provincial government initiatives. All members of the unit are seconded from partner agencies for a minimum of two years.

Inspector Jim Kennedy, ALERT’s director of intelligence, says his organization is unique. No other province has a central body for the oversight and governance of integrated provincial policing, although Manitoba is developing a similar agency. Since its inception, ALERT has laid 6,200 drug-related charges against 2,500 people, seized more than $4-million in cash and taken 300 firearms and 700 kg of drugs off the streets. But there have been lots of targets out there.

Maze says gang activity in Alberta spiked in 2006 when the province was rolling in an oil and gas bonanza and the economy was booming. “Basically, criminals outside of Alberta came here for the same reason everybody else did—the ‘Alberta Advantage,’” says Maze. “There was a lot of money to be made and lots of criminal markets.”

Law enforcement officials blame the federal Corrections Service for the spread of gangs across the country in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Maze says CSC officials began to have a problem with large populations of gang members in prisons such as Stony Mountain in Manitoba, and attempted to deal with it by dispersing them to prisons across the country. “What they did was educate other local criminals that were incarcerated… and build new gangs,” he says. Soon police were encountering Alberta Warriors, an offshoot of the Manitoba Warriors.

Maze says some of today’s organized crime groups are sophisticated and others are basically opportunists. But he says there’s been increased involvement in white-collar crimes because the profits are huge and the chances of violence and apprehension are greatly reduced. He says gangs are recruiting tech-savvy teens for identity thefts, credit and debit card scams, and even mortgage and real estate fraud. Sentences for these are not nearly as heavy as for drug crimes.

Poverty is key, but Alberta puts most of its resources into enforcement rather than social programs.

There’s also a boom in counterfeiting—not money, but goods such as appliances. Gangs also enlist people to steal specific items they then sell on the Internet. Other groups operate theft rings that take advance “orders” for specific items—everything from snowmobiles to tractors—and send out operatives to steal them. “The gang members shooting each other and injuring people are just the tip of the iceberg,” says the CISA director.

Police attempt to rein in gangs by monitoring their activities and gathering information to justify charging or, if applicable, deporting members. “We create an environment where these groups don’t feel comfortable and can’t operate,” says Maze. This fall in Calgary, the province will launch TALON, a controversial real-time law enforcement database. Eventually all 12 municipal police services in the province as well as First Nations police will be linked to a database containing records of all public interactions with police. “We’ll make it more difficult for the criminal to move around the province and commit offences, says Maze. “It will be one of the most significant changes in law enforcement in Alberta—a huge benefit to officer safety and public security.”

Ayaaz Janmohamed, executive director of the provincial Solicitor General’s information technology branch, says police currently have to individually contact each municipal police agency in the province to determine if a specific gang member was involved in illegal activities there. TALON enables a police officer stopping a vehicle for a traffic infraction in Edmonton to instantly access information about the driver’s history—everything from traffic tickets to outstanding shoplifting charges. “Information is gold for them,” Janmohamed says. “The concept is to have a single source of the truth.” Unlike the RCMP-operated Canadian Police Information Centre (CPIC), however, which contains only verified information such as criminal convictions, TALON captures “speculative” information about suspects, including unproven allegations, investigation theories, details of 9-1-1 calls—virtually any of a citizen’s contacts with police—and this has attracted criticism from defence lawyers and civil liberties advocates.

Police have begun working with special prosecutors to increase the likelihood of convictions. This was prompted by a massive drug case that collapsed under its own weight in Edmonton. Police arrested 60 people in a series of raids in September 1999, in a crackdown on an organization known as the Trang gang. About 24 people were convicted on various charges and four were deported, but after the province spent $2.1-million building a special courtroom, charges against 19 people were stayed after the court ruled police failed to adequately disclose evidence. The case cost taxpayers $36-million in policing and legal expenses. To add insult to injury, Trang gang members successfully sued the province in a nine-year-long civil suit over horrific conditions in the remand centre. A judge found they had been subjected to cruel and unusual treatment and their Constitutional rights had been violated, but no monetary damages were awarded.

Tom Engel, an Edmonton lawyer who represented 26 of the accused, says the massive investigation did little to stop the flow of drugs. Younger and more violent criminals took over the drug trade in the city and violence became even worse. “Out of that came a gang called the Crazy Dragons, and those guys didn’t mind violence at all,” he says. Engel questions the value of enforcement and suggests the decriminalization of illegal drugs would remove gangs’ main incentive. “I don’t think there’s any information that any of these specialized units that cost millions of dollars are effective at all in controlling the use of drugs.”

Police concede they will never totally shut down gangs or the drug trade. “You’ll always have gangs,” Derko says. “We’ve laid some pretty serious charges and put gang leaders in jail, but the group gets a new hierarchy and they keep going.” But he says it is necessary for police to keep the pressure on. “If we didn’t, how rampant would this be?” he says. “We might not be able to stop them, but if we keep them down so they can’t grow, that has an impact. The more money they can generate, the more power they have.”

When police arrest and courts convict gang members, it puts a strain on the prison system. Terry Garnett, director of the Alberta Correctional Service intelligence unit, says the province now posts a security intelligence officer in all corrections facilities to keep tabs on gang members, who make up 7 per cent of the prison population. He says more than 200 inmates in 25–30 gangs are in eight provincial facilities at any one time.

Another 250 are in federal institutions in Alberta, and another 100 are in local communities under federal supervision, says April Morris, a spokesperson for the Correctional Service of Canada. She says about 2,000 gang members or associates are in federal jails and 415 of those are identified as affiliated with Aboriginal gangs. Morris says nearly 25 per cent of all incarcerated gang members are serving sentences for drug-related crimes at a cost to taxpayers of more than $300 a day. The average annual cost per inmate in 2008 was $106,583.

Garnett says that when provincial inmates are admitted they’re asked to reveal, for their own safety, whether they’re affiliated with any gangs. “We know who they get along with and try to make sure they don’t cross paths in the corrections facilities,” he says. But gang members sometimes attack gang members. The family of one is suing the province and Alberta Corrections for nearly $11-million for a vicious May 31, 2006, attack at the Edmonton Remand Centre that left the victim severely disabled.

Garnett says the influence of gangs in prison is directly related to how many members of the same gang are in a jail. “The minute they show that they’re trying to control a unit, we take measures to prevent that.” Correctional officers say the increase in the number of gang members in provincial jails brings with it a heightened risk for prison staff as well. Some are concerned that risk will increase in the new 2,000-inmate Edmonton Remand Centre, currently under construction, because guards will be mingling with prisoners rather than watching them from relative safety behind shatterproof glass windows.

Locking kids up ensures an infinite supply of new gangs. Edmonton counsellor Wallis Kendal: “Talk is cheap. If you want to get a kid off gangs, give him an alternative.” (Darcy Henton)

But Alberta’s strategy against gangs is not limited to locking them up in prisons. Premier Ed Stelmach launched a safe communities initiative following his 2008 election victory, and followed up in December 2010 with a comprehensive anti-gang strategy. The four-pronged plan focuses on awareness, prevention, intervention and enforcement. It says the suppression of gangs must be led at the community level. “Traditional law enforcement has a vital role to play in stamping out criminal activity, but more arrests alone will not solve the gang problem,” says the 50-page document. “Instead we must take a comprehensive, long-term approach—one that systematically reduces the ranks of gangs by stopping the recruitment of new gang members.”

With a multi-ministry approach, the province has invested more than $500-million to fund police, prosecutors and community programs, says former justice minister Alison Redford. “That’s one of the reasons we’ve been successful,” she says. “We didn’t just implement policies. We put in a fair amount of money.”

The province also passed a series of anti-crime bills aimed particularly at gangs—legislation that empowers police to remove gang members from bars, seize body armour and impound armoured vehicles. They also passed a bill to establish a witness protection program for gang members who testify for the Crown, and a bill that makes it mandatory for medical personnel to report stabbing and gunshot wounds to police. But the most controversial legislation so far has been a revised Victims Restitution and Compensation Payment Act that enables police to seize cash, property, vehicles and other assets they believe were used in crimes or are linked to the proceeds of crime.

“Police have told us it’s a very successful tool,” says Redford. By the end of 2010, police in Alberta had seized $20.9-million worth of property or proceeds from crime and put more than $2.5-million back into the community for programs to support immigrants, women and at-risk youth.

But this tool comes with a price, say critics, arguing it gives the province too much power. Janet Keeping, president of the Sheldon Chumir Foundation for Ethics in Leadership and co-founder of the Calgary Civil Liberties Association, says that there’s little evidence from other jurisdictions that “civil forfeiture” laws reduce crime, and she notes that the law violates the provincial Bill of Rights.

Brian Hurley, president of the Edmonton Criminal Trial Lawyers Association, says the government is focusing its energy in the wrong places. He says poverty and child abandonment are key factors in kids joining gangs, but the government still puts the bulk of its resources into enforcement rather than social programs and support systems for at-risk children.

“Upper class suburban kids don’t join gangs,” he notes. “Gang members come from disadvantaged backgrounds. You rarely have a gang member who has even one parent who gives a crap about him. Kids need to be wanted and need at least one parent to take care of them, but none of that makes a good sound bite.”

Chris Hay, executive director of the John Howard Society of Alberta, warns that youth crime is linked closely to demographics, and the number of at-risk youth is expected to increase over the next decade. He says the birthrate was up 5 per cent in 2004 over 2003 and that means more at-risk teens by 2017. He says a strong correlation between fetal alcohol syndrome and delinquency makes it logical to spend money now on counselling for drug- and alcohol-addicted women to reduce the number of FAS births. “If a young person gets into crime and doesn’t get out of it, we’ll spend millions on that person,” he notes. “There’s all that enforcement and the cost of locking them up in jail. But it’s difficult for governments to step up and invest now so we can have a brighter future 20 years from now.” Hay says other strategies aren’t working. “If we think crime is a law enforcement problem, we’re doomed to failure. Gangs are a community problem.” He says, however, the government is on the right track with its investment in community programs that support youth and their families.

Some critics say policies that aim to keep people locked up just ensure an infinite supply of new gangs. Inmates scheme with other inmates with technical skills and contacts to set up new criminal enterprises when they’re released. “The crews today were made up in jail,” says Edmonton youth outreach worker Wallis Kendal. “They meet in jail.” And once in a gang, he says, it’s extremely difficult to get out. “These kids have no other way to make an income,” he says. “I have a lot of guys and gals who would get out of gangs, but they have no way to live.”

The Native Counselling Service of Alberta (NCSA), which operates the minimum-security federal institution in downtown Edmonton known as the Stan Daniels Healing Centre, has run a Warrior program aimed at curbing violence for nearly a decade. Patti LaBoucane-Benson, NCSA’s research director, says it’s possible to help people get out of gangs, but they must be motivated. “We can’t do it for them,” she says. “We facilitate a process where they do what they need to get out of gangs. We can’t make people heal, but we try to create a safe environment where they can begin to contemplate this stuff.”

Solicitor General’s office spokesperson Christine Nardella says the province doesn’t run any programs aimed at getting gang members out of gangs, but it funds several aimed at steering youth away from gangs. In late 2010, the province allocated $8.2-million to 14 agencies with a track record of supporting vulnerable youth. One youth intervention program that received $1.5-million under the Safe Communities Strategy is Pohna: Keepers of the Fire. Pohna director Karen Erickson says the program was launched in 2006 at the request of Edmonton police to reach out to youth aged 11–17 at risk of being involved or already involved in criminal and gang activity. Some teens were wearing gang colours and modelling themselves after Los Angeles gangs with names such as the Bloodz, the Blood Set Soldiers, King Pin Blood and the Blood Tie Family.

Police say gang activity spiked in 2006, when the province was rolling in oil and gas bonanza.

“We build on the strengths of kids, rather than their problems,” she says. A critical component of the program requires youths to bring key adults in their lives—a parent or guardian or relative or teacher—for support. “We try to ensure they don’t fall between the cracks,” she says. “We develop a relationship in which they feel valued, that someone is there for them, that they have somewhere to turn, that they are not alone.”

She says the support system sticks with the youths even if they falter and end up charged with additional criminal offences. It shows them a better way and helps establish a support network to get there. “They want to stay out of trouble and to stop drinking and doing drugs,” she says. “They want to move away from the group that gets them into trouble, but making all these things happen isn’t easy. A 14-year-old can’t do it alone. Will alone can’t make changes occur.”

Kendal, an outreach worker who’s been stabbed and beaten in his line of work, isn’t optimistic such programs will be successful without housing support and employment opportunities for youth. “Talk is cheap,” he says bluntly. “If you want to get a 16-year-old off gangs, you have to give him an alternative that means something.” He says programs to help prepare youth for employment have inflexible hours and pay only $1,000 a month, which nobody can live on.

Jesse (not his real name) is coming to terms with that. A former gang leader in Edmonton, he lived the life of a high roller, pulling in several thousand dollars a day. He had credibility on the street and he had power. He could give an order and people would be beaten. But a few stints in prison for home invasion and drug charges got him thinking. He was tired of always looking over his shoulder for other gangs or the police. He was tired of hurting people to collect drug debts or just because they were from a rival gang.

In jail, he saw 50-year-old gang members trapped in that lifestyle and decided it wasn’t the life he wanted. “The fact that I didn’t have a Christmas, I didn’t have a birthday, was depressing. I didn’t know every day if I would live or die. I was angry. Days were stressful—always living by the drugs and the money. I always wanted to change, but change is so hard.”

He reached for help through a NCSA program called Quest for Success, a predecessor of Pohna. It took two tries before he finally managed to cut all ties to gangs and drugs. Going back to school and finding a job were nearly impossible. Kendal got him into drug rehab and his counsellors helped him get a job. But it was a long process. Jesse had never lived a “normal” life. His mother and other relatives were drug dealers and users. He’d sold drugs since he was 13. He had to turn away from his gang buddies, from the money and the power.

Jesse, now 25, has been clean and sober for two years. He’s still going to school, has a part-time job and works with other young people trying to wean themselves off gangs. He says he would never have got this far without the programs. “Those supports are needed when someone’s trying to get out of that lifestyle,” he says. “It’s almost like teaching a baby how to walk.”

He’s enthusiastic about a new program called Uncensored, run out of the U of A. “It’s outside the box,” explains Jesse. The program enlists youth to counsel counsellors in techniques to help kids like themselves. Similar to Pohna, it gives youth power to change the way things are.

“This program is a groundbreaker,” Kendal adds. “If there’s going to be a change, it will come because the kids themselves will be the driving force.”

Darcy Henton is a veteran journalist who currently covers politics as an Edmonton-based legislature reporter for the Calgary Herald.

____________________________________________