While Darrel McLeod’s first novel is set primarily in the Indigenous Dakelh country close to Prince George, his central character, James, hearkens back to growing up in a part of Alberta with a distinct Cree presence—his people. The families and neighbours he writes about could easily have been my neighbours and schoolmates. I identified too with the familiar Vancouver scenes that open the novel—the market on Granville Island, the streets of Kitsilano.

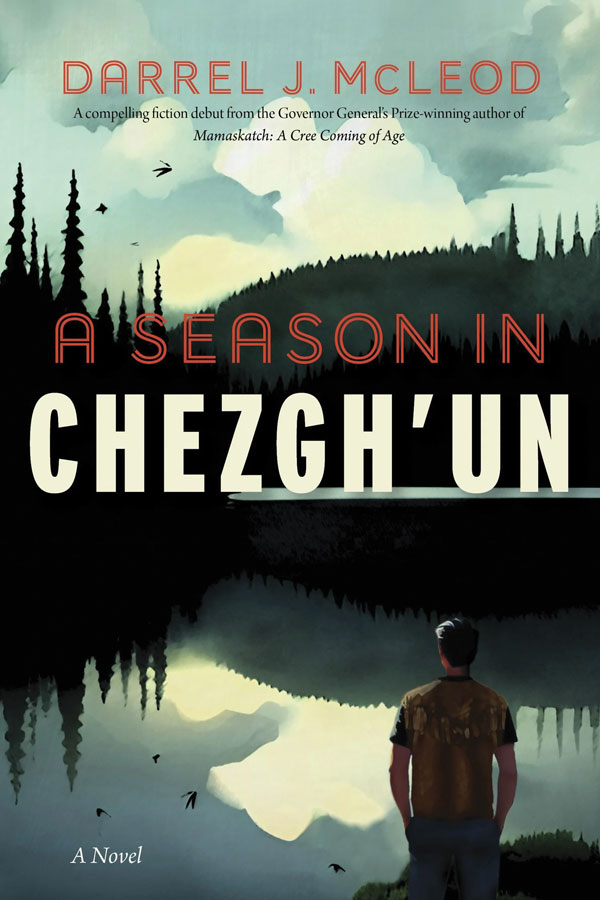

But mainly the narrative focuses on the term that James, an experienced teacher, spends as principal of a rundown school in the Dakelh settlement of Chezgh’un. With promises the school will be rebuilt along with lodging for himself, he embraces the chance to bring in newer, effective teaching methods as well as helping a damaged community heal—as a staff member says, “Our natural and cultural way of raisin’ kids was completely broken up in four generations of residential school.”

The Dakelh language is quite different from Cree, but James responds to its Indigenous textures, appreciating connections to the natural and spiritual world. Communality too is an important aspect of Dakelh culture. McLeod brings humanity and humour to many scenes, including a “bullshitting” competition around a campfire. Especially touching are episodes featuring youngsters at a fishing camp, later presenting what they’ve learned at a concert with songs and drumming. McLeod is a master of sensory detail as he writes of the food and fun involved. A sex education session with teens involving bananas and condoms will leave you laughing.

As an educator and musician, James is someone we come to admire. But he’s not without rough edges. Although he has a partner in Vancouver, he isn’t above indulging in risky hook-ups on the road. “Attractive men… were his kryptonite.” Fair enough… but AIDS, in the context of the 1980s, comes across in the novel as more of an afterthought than the terrifying presence it was for gay men then.

A Governor-General’s Award winner for his memoir Mamaskatch: A Cree Coming of Age, McLeod experiences a few bumps in this transition into fiction. We access the narrative entirely through James except for an inexplicable lapse when it shifts into a secondary character’s point of view for four pages. No editorial catch there. And, while the story emerges as it is happening, there is one jarring slip into future reflective mode: “For years afterwards, James would dream about that day, wondering what was real and what he imagined.” Still, a worthy read from an author who knows first-hand of country roads, tribal politics, the wisdom of elders and the promise of youth.

Glen Huser is the author of Burning the Night (NeWest).

_______________________________________