When Nick Zon drove onto the property on Moonlight Bay in 1973, “I knew it was the one,” he says. Willows and poplars shone golden-green in the sun. Lake waters lapped at the grassy bank. Zon, an electrician who owned his own company in Edmonton, drove to several lakes near the city that summer to find “a lakefront property for my family to enjoy.” He chose Wabamun.

It’s a large, popular lake about 65 km west of Edmonton. At the northeast corner is Moonlight Bay, a body of water as lovely as its name, with a big sandy public beach at a provincial park and many lakefront property owners.

Wabamun” means “mirror” in nêhiya-wêwin (Cree), and the situation here is a kind of mirror for Alberta.

Wabamun has long attracted praise. Early settlers called it “White Whale Lake” because of its huge and abundant whitefish. The Grand Trunk Pacific Railway Company laid out the Village of Wabamun, intended as a lakeside summer resort beside Moonlight Bay, and tourists flocked from Edmonton. “Wabamun,” wrote the Edmonton Bulletin in July 1914, “[has] the largest fleet of motorboats and launches of any lake in the province.” Commercial fishing boomed, peaking in 1956 with over a million pounds of whitefish hauled from the lake. That same year, right next to the village, the Wabamun power plant began producing electricity. When the fishery declined quickly in the late ’50s, sprawling coal mines and adjacent TransAlta coal-fired power plants to the north and south of the lake offered new jobs. Tourism continued. Cottagers built around the lake. A sport fishery thrived. Zon loved to restore old cars and built a big garage on his property. He could swim from shore. “I spent all my free time there,” he says.

In 1982 the lake water was near historically high levels. A heavy snowpack melted the following spring. One morning in May 1983 Zon noticed “a sloughy smell, like you usually only smell in the fall” when water levels drop and near-shore water plants decay. “I walked over to the weir,” he says, “and I saw a trench dug [through the weir] and it was draining. I said ‘Hell, that’s no good.’ So, I phoned the department of environment and expected them to say, ‘Thank you very much, sir; we’ll look after it.’ And here I am now, 40 years later.”

Zon and his son Dwayne met me at the weir in August 2021. He’s an older man now, thin and slightly stooped, but he walks with pace from our vehicles down a dip in the dirt road to the weir, a thick bundle of papers in his hand.

The old steel weir at Wabamun Lake was destroyed by unknown persons in the early 1980s. The Alberta government built a replacement weir—the road—at a lower level. Photo by Tadzio Richards.

Alberta lakes are in trouble. Starving fish. Shrinking water levels. Blue-green algae. Many of the 600+ lakes in the province face these and other issues: invasive species, pollutants, cumulative impacts from development and, as scientists David Schindler and Bill Donahue wrote in a peer-reviewed paper in 2006, “the impending water crisis” on the prairies due to climate change.

For those who live by, visit, use and play on Alberta lakes, the problem is what to do about the issues. The water is owned by the Crown, but lakes are subject to a range of jurisdictional oversight, from the federal government (fisheries, navigation etc.) to the province (shorelines, lakebeds) to municipalities that give local development permits. Historically, in response to problems in lakes, Albertans either advocate to solve a single issue that affects them personally or, as has happened now and again, they try and collaborate to find solutions that will benefit the health of the whole lake and all lake users. Neither approach can fully deal with the challenges.

For starters, it can be hard in this province to even agree on the problem that needs fixing.

Wabamun Lake is a good example. Moonlight Bay has weeds. That’s what lakefront property owners call the aquatic plants that grow in abundance in the shallow water. Paddling here you can see these plants underwater, so thick and high in places that the vegetation clings to the blade of a kayak paddle dipped just beneath the surface.

Are the aquatic plants a problem? It depends on who you ask. Wabamun Lake is 19 km long—83 km2, among Alberta’s largest lakes—and has many users: the hamlet of Wabamun (formerly a village), the summer village of Seba Beach, tourists, property owners, fishermen, the Paul First Nation on the east side of the lake, a railway line on the north shore and the Sundance power plant on the south side. Not everyone cares about the plants in the water. But some people do, and among them is Nick Zon.

The “weeds” are lowering property values, says Zon. Artificially low water levels in the lake are causing excessive weed growth, he claims, arguing that this problem would be solved if the government would “raise the weir.”

The weir has been an issue for nearly a century. The lake has only one natural drainage point, Wabamun Creek, a small creek on the Paul First Nation reserve, just south of Moonlight Bay. Over the years, the creek has often been dammed by beavers, which jams up the drainage point. Back in 1912, unknown people—likely farmers trying to expand cropland—dug a trench, a new outlet from the lake to drain into the creek to lower the water level. Some lakefront property owners didn’t want that, and in 1927 they built a weir at an agreed upon height to block the trench. In 1946 the province legally committed to maintain the weir.

“People think if that weir were lower the water level would go down,” says Don Meredith, a biologist and until recently the communications lead for the Wabamun Watershed Management Council. When he and his family came to the area, “and issues started coming up about the lake,” he says, “I’d go to meetings at Wabamun village, back in the ’70s and ’80s. Lake level was always one [of the issues]; it was either too high or too low. I remember with the weir early on somebody actually went and blasted the thing down. I would ask, ‘Does anybody know who did this?’ and people would say, ‘Yeah, some do, but nobody’s talking.’ ” That was in spring 1983, when unknown people destroyed the weir at night. The province built a replacement weir. But Zon and other property owners asserted that the new weir was built too low.

“I know what Wabamun used to be and what, with a little government help, it could be again.” Don Meredith

At the same time, Meredith and others tried to resolve multiple issues at the lake. Spurred by a 2004 government-commissioned report on Wabamun Lake by Schindler, a University of Alberta limnologist, their strategy coalesced around the idea that problems are best addressed by approaching lake management with a public interest mindset, as opposed to focusing only on individual concerns. Environmental issues have rarely been dealt with that way historically in Alberta. For instance, in 1985 a regional planning commission released a comprehensive management plan for Wabamun. It was “sent to all levels of government around the lake,” wrote Meredith in an article on his blog, “and it was dutifully filed and forgotten about. Why? Because of the age-old problem in this province where no one department or indeed government is responsible for lake management. The result is, on any particular lake issue, the buck is passed from one jurisdiction to another and nothing significant gets done.”

“Wabamun” means “mirror” in nêhiyawêwin (Cree), and the situation at the lake is a kind of mirror for Alberta. The lake has had booms—a commercial fishery, a long era of coal power—and now it faces decline. What is done now, at the community level and in government, could determine if that decline will continue or whether another way is possible.

Health advisory in 2021 at Wabamun Lake for blue-green algae, which can produce toxins causing rashes and sickness. Photo by Tadzio Richards.

By August 2021 the old weir is a rusting steel sheet with lake water flowing around it. The new weir is the road, which is paved with cement across the bottom of the dip, blocking the outlet. Lake water laps at the cement. It’s been a record-setting hot summer and water levels are low. If the water were higher it would flow over the cement weir into the creek, which meanders close to the lake at this spot, a low, marshy bit of ground allocated to the reserve. The new weir is visibly lower than the top of the old one that was destroyed. Zon has a blueprint of the old weir in his bundle of papers and pulls it out, struggling to hold it still as the documents flap in the wind.

Zon’s papers tell a saga. Moonlight Bay is the shallowest part of the lake, and Zon and other cottagers there wanted the weir rebuilt. It became an obsession. He organized petitions, met with government officials, researched old reports and contracts related to the weir and filed FOIP requests that revealed internal government memos related to the issue. He kept all the files.

In 1988 he and his fellow advocates met with the environment minister, Ken Kowalski. The minister agreed to fix the situation, but instead of rebuilding the old weir, the government issued itself a permit to store gravel in a waterway and built a roadway across the trench next to the old weir. This caused a new kerfuffle (the road was higher than the weir) and so the government knocked the road down to where it is now: 724.55 m above sea level, an elevation measured by a surveying company and approved by the government.

This approval is the crux of Zon’s issue. He thinks the new weir was put in 18 inches too low. Usher, the company that did the surveying, admitted in a 1988 letter to Alberta Environment that they “cannot confirm or dispute the accuracy” of the work without cross-referencing it with “benchmark” measurements made by the railway company earlier in the century. But this wasn’t done. Zon got a meeting with Premier Ralph Klein and showed him the Usher letter, urging more survey work be done at the weir. Klein’s office sent Zon a letter saying, “Everything is fine at Wabamun.” The local MLA gave the same response. As did Environment Canada, whose representative told Zon, “Nothing you’re going to show me is going to change anything.”

But Zon persisted. Through the 1990s the lake levels remained low. Aquatic plant growth increased. In 1997 Zon and other cottagers appealed to the Environmental Appeal Board about TransAlta’s Wabamun power plant, alleging that warm “cooling water” discharged from the plant into the lake was causing weed growth and weak ice in the winter. The board agreed and recommended mitigating measures, such as increased weed cutting and putting up warning signs around the lake about the ice. Zon also had documents showing the power plant was built using the old CNR benchmarks and he alleged that TransAlta built the Wabamun plant 18 inches too low relative to average lake levels—which, as he speculated in his notes, would mean that if water levels were unusually high, as in the early 1980s, the company’s options would be to “raise the plant or lower the lake.” The Board did not comment.

In 2006 Zon applied to the Court of Queen’s Bench to certify a class action suit seeking $25-million in damages against TransAlta for harming the lake and an order “requiring Alberta to raise the lake level by ‘fixing’ ” the weir. Acknowledging Zon as “a committed advocate,” the judge cited Schindler’s 2004 report to the Alberta government on Wabamun Lake, which noted that complaints about fluctuating lake levels date back to the early 20th century, with low levels leaving some “high-and-dry” and high levels leaving others flooded. “Mr. Zon appreciates the likelihood of flooding if he and the other plaintiffs prevail,” wrote Madam Justice Topolniski in dismissing the application. “[Other] class members living on a ‘flood plain’ might well view his attitude towards them as the antithesis of a fair and objective representative plaintiff…. This action… is unsuitable for class certification.”

Zon was devastated. “The merits of the case weren’t even discussed in court,” he says.

I ask if I could take a photo of him by the weir. “I would appreciate it if you wouldn’t take photos of me,” he says. “I’ve had a rough go. They didn’t take the suit kindly, me poking around and asking questions, finding this and that.”

“Who’s ‘they?’”

“I’m hoping they’re retired,” he says. He stares at the old weir, steel jutting from water, a channel carved in the bank. “Just ask yourself: Who is big enough to do this?”

He hands over a stack of papers—old reports, notes chronicling his efforts over decades, his summation of events: “Management of the lake has been delegated to an act of vandalism and an admitted error in survey.”

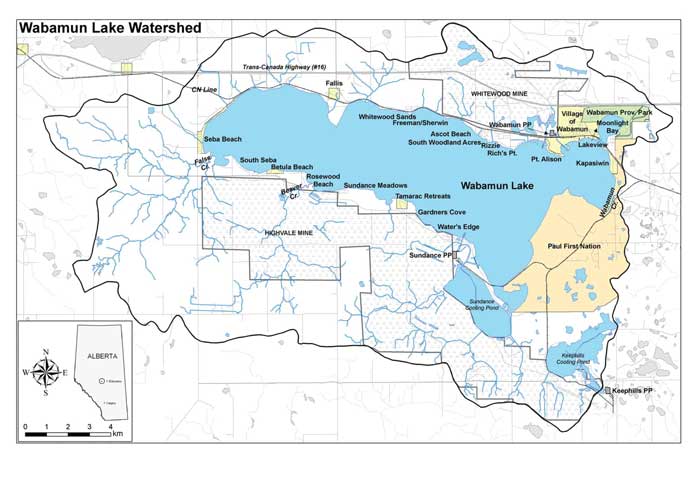

The Wabamun Lake watershed—the lake and land that drains into it—covers 259 km2 near Edmonton. Map courtesy of Wabamun Watershed Management Council.

Driving around Wabamun Lake reveals a landscape both in transition and at risk of stagnation. The power plant closed in 2010 and was imploded in 2011, a blow to employment in the Village of Wabamun, where the adjacent plant and coal mine are now fields of grass and gravel behind chain link fencing. In 2021 the village became a hamlet, joining Parkland County. Tourists still flock to the beach and boat dock in summer, but the big municipal government building in the middle of the former village sits mostly empty. From nearly any point around the lake the smokestacks of the remaining power plant—Sundance, which transitioned from coal to natural gas in 2021—are visible on the south shore, though public access to the lakefront is limited by private property, a fact communicated in road signs. No Trespassing. No Parking. No Access to the Lake. Once on the water a speckle of boats sail, jet, motor and drift with fishermen casting lines. From 2008 to 2021 it was catch-and-release fishing only here—no eating—after a train derailed in 2005 and spilled nearly 800,000 litres of oil into the lake. Anglers are now allowed to keep a few whitefish, walleye and burbot. No signs of the spill remain visible from a kayak, though greenish algae scums the surface in places, a result of naturally high phosphorus levels mixed with development runoff into the water.

“The number of lakes that are suffering is a key to understanding the whole lake system.” Ray Makowecki

Lake health decline is not unique to Wabamun. Fisheries biologist Ray Makowecki, formerly with Alberta Fish and Wildlife, says the end of what could be called the “golden era” in Alberta lakes was “roughly the mid ’80s, say, 1985.” Before that, lakes in the province were “pretty healthy [for] water quality and fish habitat and fisheries,” he says, in a phone interview. After that, “we saw decline,” he says. “One of the more dramatic changes was the drought [in the mid ’80s and again in the early 2000s]. We lost about 35 lakes in northeast and central Alberta—they no longer supported fish, simply because of declining water levels.”

Among lakes similar in size to Wabamun, Muriel Lake, near Bonnyville, saw dramatic water level declines and lost all its pike, perch, whitefish and walleye sport fish. Pigeon Lake, 108 km southwest of Edmonton, also saw water level declines, along with outbreaks of toxic blue-green algae. “Increased development, land use changes and increasing populations” were all factors, says Makowecki. While some lakes are “coming back” in terms of fish numbers, he says, “the number of lakes that are suffering, or have suffered in the past, is a key factor in understanding the whole lake system” across the province.

Consistent with this big-picture view, declining sport fish populations and other issues at Wabamun were obvious by the end of the 1990s. The Alberta government contracted David Schindler—Alberta’s most prominent environmental scientist—to chair a committee of experts to review previous studies and make recommendations to guide future management of the lake. Along with better monitoring of water quality and an end to “overfishing,” Schindler’s 2004 report recommended “that a permanent citizen panel, whose objective it is to protect the health of Wabamun Lake… be established and maintained. This panel must have members who are selected by, and representative of, the community of Wabamun Lake users.”

“There is no coherent provincial monitoring program for lakes in Alberta.” Bill Donahue

Bill Donahue, a member of Schindler’s expert committee, says they recommended the citizen panel because of “a lack of transparency, accountability and public responsibility when it comes to Alberta Environment and their decision making.” The recommendation, he says, “was in the wake of hearings out at Wabamun for the expansion of coal power plants.” Donahue had presented evidence at those hearings that “showed significant, clear and huge increases in all of the pollution associated with coal mining in terms of metals, organic contaminants, chemicals, starting pretty much exactly when coal mining and coal burning started in the Wabamun area.” Consultants hired by industry, however, claimed the opposite, presenting data that Donahue said was “literally laughable.” Instead of submitting their data for peer review, he says, “they wanted me to engage in a public tour where we would go and give our competing presentations. I said, ‘Why would I do that? You’re wrong. I’m not going to debate you if you don’t even know enough to know you’re wrong,’” he says. “Alberta was pretty complicit in that. Deceptive public communications by both industry and government were why one of our recommendations was for a citizen panel—to provide transparency” at a ministry that “should be responsible for the sustainable management of the environment in a dispassionate and unbiased way.”

Formed in 2006, and initially under the auspices of Alberta Environment, which provided funding and a secretary, the Wabamun Watershed Management Council included representatives from local communities, provincial and federal governments (though Environment Canada only attended one meeting) and environmental and recreation groups. “We spent the first couple of years just learning about lake biology,” says Don Meredith, a member of the panel from the beginning. “We wanted to write a plan, but we never got on to it,” he says, because the provincial government “didn’t know what this is—coming up with a watershed management plan. That was new ground. As a result, we had a lot of turnover of [volunteer, non-remunerated] council members; people got tired and said ‘I don’t want to do this anymore,’ leading to nothing. But some of us stuck around. And we finally got things moving. But it took a long, long time.”

And frustration. As Meredith wrote in a 2014 article on his blog, at one early meeting, “after I had repeated what a fisheries biologist had previously told the council about pike needing aquatic vegetation in which to spawn and how cottage development had destroyed much of that habitat,” another council member replied, “Well, the fish are going to have to get out of the way. I will not have weeds growing in front of my house!”

“The point I was trying to make at that early meeting,” wrote Meredith, “was that the lake’s fish populations were indeed the ‘canaries in the coal mine.’ If the fish were not thriving, it might indicate the lake’s health was in some kind of trouble, regardless of whether you had vegetation growing in the water in front of your cottage or not. And if the lake’s health was in trouble, then many of the reasons why people come to the lake were threatened.”

With the health of the lake “slowly deteriorating,” says Meredith, the now independent council (Alberta Environment withdrew funding in 2010) identified key threats to the lake such as blue-green algae and cumulative impacts from development and climate change. The weir was not among them. “The lake level of Wabamun is largely governed by the amount of snowfall over the winter and rain events or dry spells during spring and summer,” reads the council’s website. “Evaporation… is the chief cause of water loss,” and the effect of Wabamun Creek (and the weir) on the lake is “like a straw draining a swimming pool.”

“People think we should be able to control the water level a lot easier,” says Meredith, talking about the “straw” wording. “It’s been quite the issue. We were trying to tamp it down.”

In 2020 the council, now mostly composed of lakefront property owners, organized a “steering committee” representing local municipalities, the province, TransAlta and others to come together—“it was like herding cats,” says Meredith—to review, agree on and release the Wabamun Lake Watershed Management Plan, essentially a non-binding plan for action.

“Every day, provincial, municipal and Indigenous governments, industry, private landowners, and others in the Wabamun Lake watershed make land use and other decisions that can affect lake health,” reads the plan. “While many of these decisions are well intentioned, it is difficult to see the ‘big picture’ and [to see] if individual actions by different jurisdictions are complementary to lake and watershed well-being. A watershed management plan is meant to provide this landscape-level view … [and to help] coordinate who is doing what, in order to ensure activities are integrated and that they lead to a collective shared goal or outcome.”

Guided by a shared vision of the lake watershed—“a healthy ecosystem with a robust economy and a thriving community”—the plan recommends using the precautionary principle for all lake management decisions. It also details priority areas for action such as more water-quality monitoring, shoreline restoration, and better alignment of policies and plans between different levels of government. “Where possible,” said the steering committee, these actions should be done through “existing budgets” and “existing stewardship initiatives.”

Quoted in Alberta Outdoorsmen magazine, conservationist Lorne Fitch praised the council for “the herculean task of preparing a watershed management plan.” But he cautioned that community-led landscape-level planning has historically been hampered by the provincial government offering “empowered” citizens “little in the way of resources [and] little or no technical assistance.”

Meredith, quoted in the same article, agreed. “I hang in there because I know what the lake used to be and believe that with a little government help it could be again.”

Across the lake from the Sundance power plant, a train derailment spilled oil into Wabamun Lake in 2005. Photo by Tadzio Richards.

Waiting for government help could be in vain, says Bill Donahue. He has a Ph.D. in aquatic science and a law degree, both from the University of Alberta. In 2015 he was appointed vice-president and chief monitoring officer at the independent Alberta Environmental Monitoring, Evaluation and Reporting Agency (AEMERA). That agency had been created in 2014, after a research team led by Schindler found that oil sands pollution wasn’t being detected by Alberta’s environment ministry, a finding that sparked international outrage, embarrassing the government into creating the independent body. When the NDP government folded AEMERA back into government, Donahue stayed on as executive director of science in the new Environmental Monitoring and Science Division (EMSD). The entire project was hampered by a lack of funding, he says, citing “dishonesty, incompetence and intentional deception” at the highest management levels of the ministry as reasons why he resigned in 2019, not long before the UCP dissolved the EMSD as an entity in the department.

“There is no coherent provincial monitoring program for lakes in Alberta,” Donahue says. As a result, “in many cases you’ve got community groups or cottage associations trying to do their own community-based monitoring in the absence of any leadership and resources from the province. So, you’ve got fractured and disjunct decision-making based on fractured or absent information about lakes—their status, what’s going on, there’s no real understanding of what specifically is affecting any individual lake.”

The NDP government made a mistake when it brought AEMERA back into government, he says. “AEMERA was created [to do environmental monitoring] in a way that was transparent and scientifically defensible and not driven entirely by a need to defend fill-in-the-blank industries’ priorities, whether its oilsands or coal mining or power plants or oil and gas,” he says. “That’s similar to the reasons why we recommended that public panel [at Wabamun Lake], which was that the department had shown itself to be either unwilling or unable to properly deliver scientific environmental monitoring and assessment.

“Ideally that should be done by government,” Donahue says. “That is the role of government. A ministry of environment is responsible for managing the environment. And I would say arguably responsible for doing that in a way that respects the public will and protects the public interest. But Alberta Environment is not capable of doing it.”

Tadzio Richards is associate editor of Alberta Views.

____________________________________________