Shahab Ahmad was born in the state of Bihar, in eastern India. He left India to study for his Ph.D. in psychology in Glasgow, Scotland. Like many Muslims before him, Shahab benefited from Canada’s relaxation of federal immigration laws under Pierre Trudeau. In 1968 Shahab moved to Halifax, where he lectured at St. Mary’s University. Later his family moved to Alberta.

The Ahmad family’s home is in an expansive suburb on the outskirts of south Edmonton. On the walls are ornate Islamic decorations. One particularly eye-catching frame contains the 99 names of Allah, in thick and thin lines of Arabic script. Three generations of the Ahmad family live here: Shahab, his son Mobarak, his wife Fozia, their two boys, Khalid, 25, and Haris, 21, and daughter Sidra, 14.

It is the middle of the holy month of Ramadan, the Islamic fasting period of 30 days. By the time the Ahmad family sit down to eat after sunset, they have been without food for almost 14 hours. Edmonton’s long days of summer present the Qu’ran’s call to fast from sunrise to sunset at almost its most physically challenging.

Each family member has their favourite Ramadan food, all rooted in the family traditions of Indian and Pakistani cooking, such as black chickpeas, aloo pakora and beef with potatoes. During the meal the family chat enthusiastically about Fozia and Mobarak’s impending trip to Mecca to complete the Hajj, a pilgrimage conducted around two and a half months after the end of Ramadan. Last year the Ahmads’ other children visited Mecca for the Umrah, a pilgrimage conducted at any time of the year. The restrictions in Saudi Arabia gave the whole family a sense of the abundant freedoms available to them as Canadian citizens. Fozia describes life in Edmonton as rewarding for Muslims. “We have freedom of speech and freedom to write and have little fear of attack, compared with my sister who lives in America. We are blessed to be in Canada. People accept how we are.”

“We have freedom of speech and little fear of attack. We are blessed to be in Canada. People accept how we are.”

Over the evening, conversation touches on many topics: rising tuition, the tightening job market, gay–straight alliances and the Islamic perspective on climate change. This well-educated family seems comfortable with any subject, and it is clear they have drawn on Islam’s rich heritage to forge a life in North America that is congruent with both Islamic traditions and Western ones.

As Muslim-Canadian families seek to intensify their engagement with Canada, the question becomes to what extent Canada is willing to fully embrace their involvement. The Ahmads are members of the Ahmadiyya movement within Islam. On July 5, 2008, the Ahmadi community celebrated the opening of the Baitun Nur mosque in Calgary (Canada’s largest mosque, and spiritual home to 2,500 Muslims). Prime Minister Stephen Harper attended the opening of the mosque and praised the Ahmadiyya movement as exemplary: the “true face of Islam.”

While the community appreciated this endorsement at the time, the policies of the Harper government became increasingly harsh toward Muslims in the years that followed. While pursuing an anti-terrorism agenda and joining the military resistance to ISIS in the Middle East, the Harper government took steps domestically that exerted negative pressure on Canadian Muslims. On the tenth anniversary of the 9/11 attacks Harper gave a TV interview in which he identified “Islamicism,” rather than terrorism, as the major threat to Canadian security. Speaking in Parliament in January 2015, the Prime Minister directly linked Canadian mosques with the radicalization of young people wanting to fight for ISIS in Iraq and Syria.

His comments were described as “troubling” by the National Council for Canadian Muslims and the Canadian Muslim Lawyers’ Association, who accused the Prime Minister of fostering a climate that led to mosques being vandalized. Just two months later Harper was back on the offensive, describing the niqab, a cloth covering the face, as originating in a culture that is inherently “anti-women.”

Harper’s public statements about Islam were backed by far-reaching policy changes. In 2015 his government passed Bill C-51, a comprehensive security package criticized by Canadian civil liberty groups, including Muslim organizations, for stoking a climate of fear. One measure targeted dual-citizenship holders who, if convicted of terrorism or treason, could now be stripped of their Canadian citizenship and deported to their country of origin. Even though the overwhelming majority of Muslims had nothing to fear, the measure created a sense of a two-tier citizenship among those who were not born in Canada.

The Conservative government’s objections to the niqab had shown up earlier. In 2011 Citizenship Minister Jason Kenney introduced a policy banning anyone from covering their face during citizenship ceremonies. The policy was clearly aimed at Muslim women who choose to wear the niqab. After the policy was introduced, the Conservatives campaigned to secure public support by inviting people to sign an online petition backing the Prime Minister’s argument that it is “offensive that someone would hide their identity just at the moment they are joining the Canadian family.”

Zunera Ishaq, a Muslim woman living in Mississauga, challenged the policy in the courts. In February 2015 federal judge Keith Boswell ruled in favor of Ishaq, agreeing that the government’s niqab policy denigrated the religious beliefs of Muslim women. The Harper government appealed the decision to the Federal Court of Appeal and lost again. In September 2015, in the midst of the federal election, the government declared it would appeal again, this time to the Supreme Court of Canada—and asked for a stay of the FCA niqab ruling such that Ms. Ishaq could not become a Canadian citizen in time to vote in the fall election. Again the court refused.

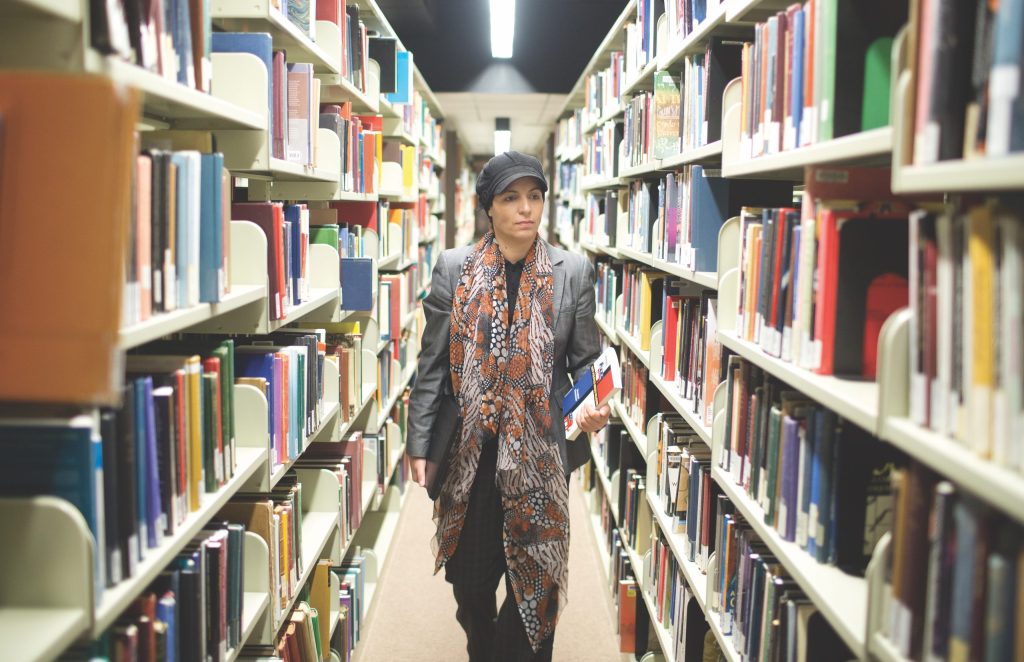

Palestinian born researcher Ghada Ageel pictured at the UofA in Edmonton, Alta., on Monday October 26, 2015. Jason Franson for Alberta Views Magazine.

By this point, everyone knew that Stephen Harper was using the niqab to stir up anti-immigrant resentment to get votes. The promise of a barbaric practices tip line, basically an encouragement to spy on immigrants, was the next ploy. All of this went against policies of multiculturalism and personal freedom that have defined Canada in the past.

“The announcement was that no one in the niqab could become a citizen! No one in the room was wearing a niqab.”-Ghada Ageel

Of the Muslim women I spoke to for this article, some choose to cover their hair, while others do not. Regardless of their personal choice, they are united in their perspective on the niqab. It is a powerful symbol around which they are eager to give voice in defence of their religion and their culture.

Ghada Ageel, a Palestinian-born researcher at the University of Alberta, attended two citizenship ceremonies in 2015: first for her husband and three children, then, six months later, her own. “We chose this country,” she says. “But on this day, what was the sweetest day of my life—the day I became a Canadian citizen—an announcement came at the start of each ceremony that no one in niqab could become a citizen! Even though no one in the room was wearing the niqab, they still made this announcement. How can you attack my culture and my history like this?”

Ageel strongly refutes any security arguments regarding Muslim face coverings, and views the government policy as a refusal to see Islam as part of the tapestry of what it means to be a Canadian citizen.

Her 19-year-old daughter, Ghaida, went to Edmonton’s largest high school, Jasper Place, and participated in the student-run Global Café, where she learned about citizenship and human rights. She takes a more tempered view. “I can understand why people are fearful of the niqab when it is not part of their culture,” she says. “In our culture we are more used to it. For us it is more normal. I choose not to cover my hair. But coming from evening prayers in the mosque, I do have my hair covered. We go to the Tim Horton’s and the staff reacts very differently to me.”

When Fozia Ahmad moved to Edmonton, she had just completed her medical training in Karachi. She was moving for an arranged marriage with Mobarak. “Being a physician,” she says, “we always evaluate a patient by looking for what is really underneath their sickness. It is the same for this law: Is it really for security or is there something hidden? There are Muslims who do wear the hijab or the niqab and Muslims who do not. They are not forced. If the government is forcing something by law, then who is the oppressor?”

Mobarak saw the politics of the situation during the federal election in 2015. “Polls said most Canadians were in favour of this ban, so that tells me it was a vote-getter. But the law had no value. The government has no business telling anyone what to wear or not to wear. The government of Saudi Arabia has a very strict set of laws telling women what to wear. What is the difference between telling women what they should wear and telling women what they should not wear?”

In episode one of CBC’s hit sitcom Little Mosque on the Prairie rumours fly that one of the Muslims in the fictional Saskatchewan town of Mercy is a terrorist. The local radio shock-jock stokes fears about the fledgling Muslim community, and a local Muslim businessman becomes the focus of speculation. It emerges that well-regarded community figure Yasir is behind the establishment of a secret mosque in the parish hall of Mercy’s Anglican church. Yasir’s wife, Sarah (communications adviser to the mayor), is shocked to hear the allegations against her husband. “But Yasir couldn’t be a terrorist. He’s a card-carrying member of the Conservative party!”

In the TV series, the town’s Muslims tread the lines between being accepted members of the community, running businesses or working in the local hospital, and being seen as dangerous hardliners who don’t belong in small-town Canada. The experience portrayed in the comedy series reflects many of the struggles of Canada’s real-life Muslims who felt increasingly alienated by government policy during the Conservative regime.

The rise of the self-proclaimed Islamic State and lone-wolf attacks on Canadian armed forces members in Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu and Ottawa led to government responses that seemed to target Canadian Muslims. More was made of ISIS recruitment in Canada than of the efforts of Canadian Muslim leaders to condemn ISIS and to support communities affected by war across the Middle East and North Africa. A growing sense of alienation was the inevitable result.

The longer story of Alberta’s Muslims is that of an earnest partnership between Muslim and non-Muslim communities. The rich history of Muslims in Alberta began with Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier’s desire to populate western Canada. To that end, his government relaxed immigration laws at the turn of the 20th century. Laurier declared that Canada would become “the star towards which all men who love freedom and progress shall come.” Muslims, escaping from compulsory military service in the Ottoman Empire, responded to this call. Some chose northern Alberta as a place to settle.

Retired schoolteacher Richard Amid is an avid historian of the Muslim community in Alberta. His father arrived in London, Ontario, from Lebanon in 1901. Working as a peddler, with a case full of knick-knacks on his back, Amid’s father saved enough to open a general store in Brandon, Manitoba. He married a Ukrainian woman who converted to Islam and they moved to Edmonton in 1927. Describing these pioneering Muslim Albertans, Amid says, “They developed strong relationships with the indigenous community, learning their language and their trapping skills. Some Muslims established mink ranches in areas such as Fort Chipewyan and Fort McMurray. Others were drawn to Calgary by the possibility of work with the Canadian Pacific Railway.”

With the community’s growth came the desire to pass their language and religion on to the next generation. The first mosque in Alberta—the first in Canada—was located at 108th Avenue and 102nd Street in Edmonton. Muslim storeowners contributed the building supplies, and Ukrainian tradesmen did much of the construction. The mosque’s name was al Rashid, meaning “the rightly guided.” It opened in 1938.

Of al Rashid mosque’s early days, Amid says, “Muslim and Arab people are very hospitable. The mosque was opened regularly on Sundays for non-Muslims to participate in meals. The relationship between Muslims and non-Muslims was very good. My brother worked for Hymie and Marvin Weisler and later bought the business from them. The Jewish fur traders on 101st were constantly trading with the Muslims.” Twenty years after al Rashid opened, Lebanese Muslims in Lac La Biche started construction of Canada’s second mosque.

Belal Salla, left and Talal al Khoudry of the Universal Barbershop, tend to customers in Edmonton, Alta., on Friday October 16, 2015. Jason Franson for Alberta Views Magazine.

In the 42 years after al Rashid opened, until 1980 when it closed its doors, Alberta’s Muslim population grew from around 200 to almost 16,000. Today al Rashid is conserved in Fort Edmonton park as an official part of Edmonton and Alberta history. The most recent census showed 115,000 Muslims in Alberta, about 3.2 per cent of the population—in line with the national average. There are just over one million Muslims living in Canada today.

“We are just normal people looking to have normal lives. All this difficulty is politics. It has nothing to do with religion.”- Talal al Khoudry

The sense of an overbearing government interfering in people’s lives, and the unsettling perception that citizenship rights for particular groups are being eroded, has a long history for Muslims living in the western world. A standard criticism in western countries is that to be a Muslim one cannot be a westerner, that Islam is somehow incongruous with western values because of its treatment of women and apparent failure to embrace free speech.

In Western Muslims and the Future of Islam, Islamic theologian Tariq Ramadan says, “We are currently living through a veritable silent revolution in Muslim communities in the West: more and more young people and intellectuals are actively looking for a way to live in harmony with their faith while participating in their societies.” However, attacks by violent groups in Europe and the Middle East—and the 2014 murder of Cpl. Nathan Cirillo in Ottawa—have fuelled the portrait of a humourless, oppressive and violent religion, despite the diversity of 1.6 billion Muslims around the world. Palestinian-American intellectual Edward Said observed how, in the western imagination, Arabs are associated with “bloodthirsty dishonesty,” a caricature rooted in centuries of European Islamophobia.

For its adherents the true face of Islam is different. “Islam,” according to Tariq Ramadan, “is a quest for the liberation of [believers’] inner selves in a global world dominated by appearances and excessive possession and consumption.” While there are differing schools of thought, from reformists to traditionalists and literalists (or fundamentalists), there is agreement on the basic principles. To be Muslim one must profess faith that there is only one God and that Muhammad is his Prophet (shahada); pray towards Mecca five times a day (salat); give a percentage of your income to charity (zakat); make a pilgrimage to Mecca (hajj); and fast during Ramadan (sawm).

Beyond these five “pillars of Islam,” views diverge on the importance of the veil (hijab), the precise nature of jihad (definitions range from “holy war” to “internal spiritual struggle”) and the permissibility, or otherwise, of polygamy. How Muslims adjudicate these questions depends primarily on their cultural context. Muslim policy-makers in more patriarchal societies rely on conservative jurisprudence. In more liberal environments, Muslims tend to read the Qu’ran and hadith (sayings of the Prophet) more progressively.

The Muslims I have interviewed believe that Islam is clear and that those who violate its teachings—particularly through violence—are not Muslims and do not represent their views. Through mosques and in their own lives, local Muslims are actively working to explain the tenets of their faith. The Ahmadiyya community has an ongoing Canada-wide outreach initiative called “Meet a Muslim.” In November 2014, Khalid Ahmad, 25, president of the Ahmadiyya Students’ Association at University of Alberta, organized a conference called “Stop the Crisis.” The conference discussed the question of radicalization and set out to educate young Muslims about the teachings of Islam. Of the young men joining ISIS, Ahmad says, “It stems from a lack in their personal religious education. Their views aren’t representative of the Muslim faith.” Around 50 people, mostly young Muslims, attended. The conference generated headline coverage on local TV and radio stations.

Talal al Khoudry, a Whyte Avenue barber known for his quick hands and neat cuts, believes that the battle against radicalization must include a positive contribution to solving the humanitarian catastrophes in the Middle East. Before departing for Lebanon to visit his mother, al Khoudry was inundated with offers of money and other kinds of support. He says, “Any Muslim is the brother of another Muslim. The fundraising in the mosque is constant. I know Muslim psychologists here who are speaking with traumatized clients on Skype every day. I know of a Pakistani doctor sending money over to help. Giving to those who are less fortunate is part of our religion.”

Al Khoudry’s colleague, Calgary-born Belal Salla, his hands fresh from a busy afternoon cutting hair, tells me, “We are just normal people looking to have normal lives. All this difficulty is politics. It has nothing to do with religion. I want everyone to know that we are just normal people looking to do the best for our families and the people we love.”

Eóin Murray first became interested in the complexities of Islam while living in Gaza. He now calls Edmonton home.