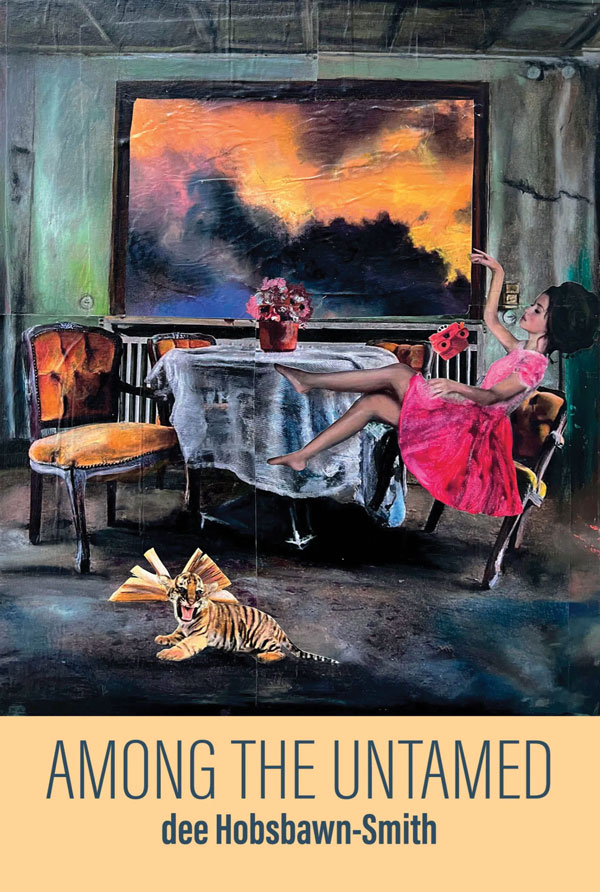

The front cover—a woman in a pink dress tipping back in a chair, a tiger cub, flowers, a pleated tablecloth, an ominous sky—encapsulates the subject matter in dee Hobsbawn-Smith’s fiercely sensual poems in Among the Untamed. Hobsbawn-Smith is a chef, and her awareness of food, used literally or metaphorically, is evident, whether it’s the “half a halibut from the white chipped ice” in the evocative “The Only” or the “stretched taffy” of time in “Jeanne Dark’s full disclosure: a haibun.” She’s also certainly not afraid of veering from delicious, mellifluous ingredients to the harder sounds of “fucking” or “the reek of stressed metal,” a focusing in sharply to the harsher realities of the countless missing women from New Delhi to Port Coquitlam, all at the brute hands of men and their weapons: handcuffs, a mallet, needles, cocks (from “Quotidian, female”). That feminist sensibility underlies all the poems in Among the Untamed, a voice that speaks to how women have been suppressed, shamed, sundered.

Hobsbawn-Smith’s ferocious championing is crucial in a time when what makes a woman a woman is more problematized than ever. But this necessary message does not always produce potent poems. The thread linking the collection encompasses lyrics and longer pieces for a character called Jeanne Dark (a riff on and at times a direct reference to Jeanne d’Arc). Yet, while such recurrent personas and their associated motifs can prove a powerful tactic (as in Tim Bowling’s Tenderman poems), Dark often doesn’t have the necessary emotive oomph, mainly because the language slips into staleness. For instance, in “Jeanne Dark leaves the sheltered corner” the persona speaks in banalities such as “bearing witness” or “Giving voice to the speechless,” and uses abstract terms such as “evil,” “peace,” “cruelty.” While in poems such as “Where stones gather,” Hobsbawn-Smith is precise in descriptions of “blue ice… wolf willows, orange rosehips” and fresh in the depiction of a “November-coloured dog,” other pieces struggle to transcend their soapboxes to make us see (and feel!) the horrendous injustices.

The lengthy segment that draws on lines from Saskatchewan poets to interrogate gender constructions, “Jeanne Dark comes of age on the prairie,” is the most effective use of this figure, as it is varied, specific and haunting in its bleak registers: “I’ve forgotten the airsongs–/ Chinook, Mistral…/ voices silenced among Quonset huts and shafts and buried stones/ roughened from mined-out green amber and dwindling raw umber…/ I’ve settled for dull olive mud that pools in a tailings pond.” In Among the Untamed, the “body rewritten” as the world is Hobsbawn-Smith’s essential testament.

—Catherine Owen is the author of Moving to Delilah (Freehand).

_______________________________________