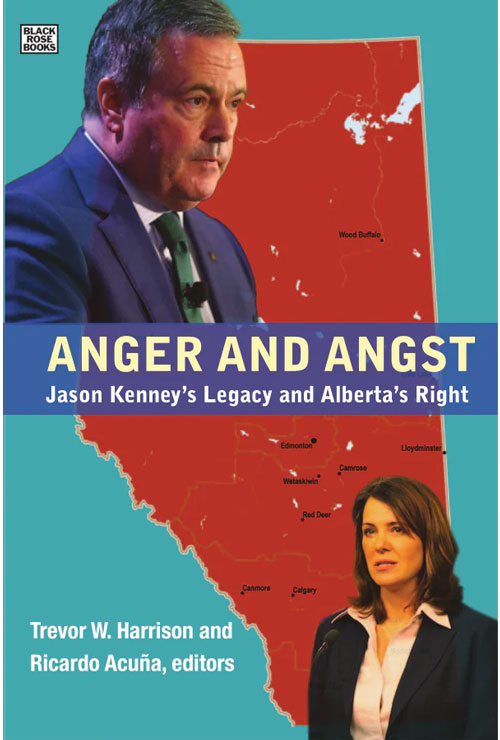

After the UCP’s recent provincial election win, reading about UCP policy and politics in the Kenney era may not have much appeal for readers. Making sense of the next four years of Danielle Smith’s governance will require a critical assessment of the first UCP government, however, and to that end, Anger and Angst will be a valuable if sobering resource. Editors Trevor Harrison and Ricardo Acuña have recruited a wide range of UCP regime critics and policy specialists to evaluate the Kenney era. Their contributions complement the editors’ introduction and conclusion, which focus on the UCP’s manufacture of resentment towards alleged elites and enemies of freedom. Harrison and Acuña portray this as the latest expression of a standard Alberta conservative “Trojan Horse” strategy for disguising the real levers of elite power. They expect this strategy to be pushed to even greater extremes by the faux-sovereigntist “populist libertarian” Danielle Smith.

Early chapters by Janet Brown and Brooks DeCillia on Kenney’s “nasty, brutish and short” stint as premier, and by Acuña on Kenney’s career, offer important insights into the UCP’s creation, its 2019 victory over the NDP, and Kenney’s precipitous decline in popularity. Chapters by Laurie Adkin and Kevin Taft on environmental and energy policy highlight the petro-statist nature of UCP governance in these linked policy realms, but Adkin also stresses the promising expansion of provincial environmentalist opposition to “extractivist” government policy over the past few decades. The privatizing and often US-conservative-mimicking UCP perspectives on education, labour, Indigenous issues, childcare and women’s policy are critically assessed in chapters by Bridget Sterling, Marc Spooner, John Church, Yale Belanger and David Newhouse, Susan Cake and Lise Gotell. For urban readers in particular, Laticia Chapman and Roger Epp’s chapter on rethinking the politics of rural Alberta is not to be missed.

Only a minority of UCP voters believed they were endorsing the Smith UCP’s broad agenda in 2023. The majority were simply voting for the most viable conservative party, with less enthusiasm than had brought Kenney to power in 2019. This disconnect between public opinion and the UCP policy agenda deserved more attention in this volume, especially since recent behavioural data allows this case to be easily made.

Alberta has finally entered the realm of competitive party politics. The UCP may lose the 2027 election, after another layer of urban voters abandons a government even further out of step with most Albertans’ policy preferences. However, we shouldn’t expect that party strategists’ concerns over such a loss will moderate UCP policy. Starting in the late 1970s, conservative parties in the US, UK and then Canada were taken over by ideologically extreme factions without losing many of their long-time, centre-right voters. When mainstream conservative parties are captured by a once marginal right wing, newly skilled in the dark arts of populist performance, moderate centre-right members and activists have found it extremely difficult to reverse their parties’ direction.

The difficulty of such reversals has been evident both nationally with Harper’s and Poilievre’s leadership of the Conservative Party and in Alberta after Jason Kenney succeeded in sacrificing the Progressive Conservative party to Wildrose extremists. Alberta voters now face conservative party organizations dominated by leaders, operatives, staff and activists whose market (and/or religious) fundamentalism justifies climate change inaction, a strikingly inegalitarian social and economic policy agenda and an embrace of undemocratic election campaign and governing tactics. For those who wish to understand the Smith UCP government’s variation on this theme, Anger and Angst is a good place to start.

David Laycock is a professor emeritus of political science at Simon Fraser University.

_______________________________________