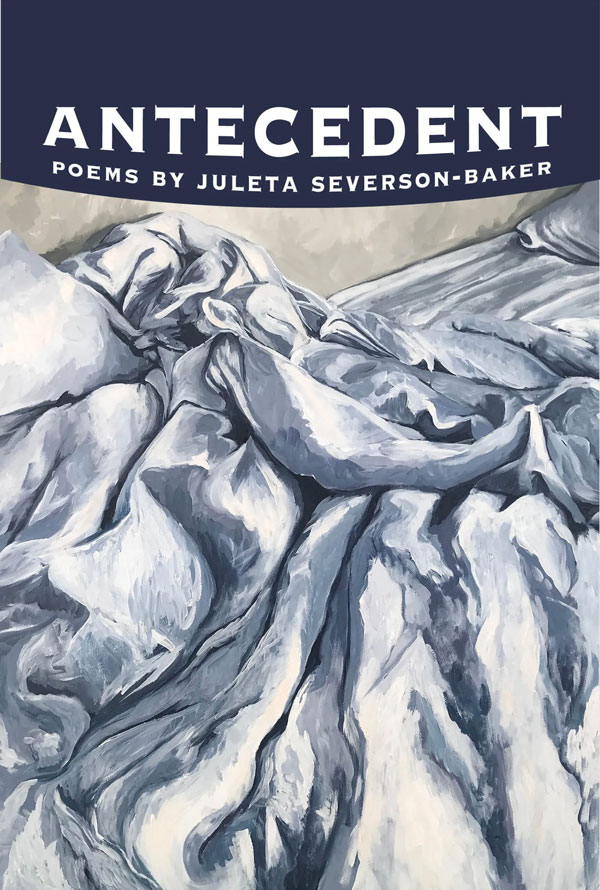

“Is this fifty? Everything on repeat?” Juleta Severson-Baker bemoans accurately in the crisply designed collection Antecedent, her poetry unabashedly addressing mid-life ennui, the persistence of familial affections, the inevitable loss of parents and the depths of her connection to a prairie landscape. Her ear is immediately evident in the poem “My Father,” which details scenes of natural world violence in his childhood, including a turtle left to die that had a “gnathic snap.” Scientific or somatic diction holds the most potent sounds in this book, such as the spores that “replicate hyphae” in “Forgotten Song of Life,” the “buttery lungs” and “covalent bond” in “A Molecule of Oxygen Speaks about What it’s like to be Sung by a Talented Soprano” (quite the title!), and the “sisters of the snapped graph” in “The Best Part of a Story.” Then there’s the delectable word “niffling,” in “Choosing,” along with the sonorous “leechy, green” edgewater of “Remember Red Deer.”

While the subject matter is familiar and yet still rendered powerfully, and the language maintains a resonance, Severson-Baker’s use of inconsistent lower case and erratic stanza breaks can distract. Also, the final section, “The Debbie Poems,” a long and ambitious lyrical playlet featuring two characters, the eponymous one, the Poet, and a Chorus of either “Calgarian elders” or nature, might have benefited from a further fleshing out of the central “Everywoman” character. Her believability needed to be enhanced so that the reader is readily able to envision such leaps as Debbie does between being a teen in 1987 on one page and an eight-year-old in 2016 on the next. The premise is fascinating but would have been more compelling if the characters interacted with each other through dialogue, the Poet sharpening their protagonist/antagonist role to more engagingly ground Debbie’s vast attributes: “siren Debbie/ debunking Debbie/ Debbie is a pine tree.”

Antecedent’s core energies are most prominent in many of Severson-Baker’s searingly moving lyrics, for instance in “My Mother of the Stiff Upper Lip,” in which lupus turns her mother’s brain into a “little starburst” of lost language; or “Farewell to Oread,” where the dying give “hugs hard as rocks”; or “We Don’t Need Language to Know Love,” a painful paean to a mother who can no longer swallow “summer plums/ roast chicken/ water.”

“Sunlight is hard to understand/ through this grubby window,” she writes in “When So If Or,” in which the hope is that the house finch returns, perhaps from a “gust of love.” Antecedent’s poems are particularly attentive to the elegiac crux of being human, where, whether to older age, death or even within perceptions of the land, you have to “go alone.”

Catherine Owen is the author of Moving to Delilah (2024).

_______________________________________