They’re sending me to art camp for the whole summer in Deadsville, Alberta. I’m packed up, prisoner in my neck brace in the back seat. Dad drives the Chevy van a shade over the speed limit down Highway 2. Mom keeps her eyes on the road. But I’m back in the pickup, making the first tracks down the alley in soft May snow, rounding like a dream into the driveway. Jason cut the motor and pulled me to him again. The dinky clock shone 4:09. The only sound, our breathing. The lane light sparkled snowflakes, kisses, sweetness.

Dad is saying this town’s not so bad. The boys had lots of tournaments here. They’ve got a decent rink, and there’s a burger bar near the soccer centre. On Main Street, Mom gets excited about a quilting store. That’s all there is. Oh, and a 7-11. Big whoop if you like Slurpees. I know why they’re doing this. Because of Jason.

We didn’t hear the van until it cranked up the driveway beside us, doors slamming in the night. Dad yanked me out of the truck. What the hell are you doing bringing my daughter home at this hour? Mom hit Jason’s window. Jason flipped his baseball cap backwards and fast turned the pickup out, swerving, slipping on snow, and my door closed on its own. Snowflakes gently landed on my nose and hair, but I shook them off, running after Jason.

The camp building, a community college, is low and sprawling, unlandscaped. Prairie burnt dirt and weeds lead up to a grey door, scratched and abused by boots. Inside the door, bursts of colour, walls covered in student art, invade. I can’t look, and avert my eyes. Then they leave me in my room, which is blissful beige. They promise to call. I don’t. I phone Jason instead. I leave messages.

The last time we went out, after June exams, Jason got his shoulder yanked out. It was an accident. An aborted left turn got us hit from behind, and I don’t even know if he’s out of the hospital. His face got cut up. His pickup was totalled. The first thing I saw, after, was the clock, cracked. The whiplash hurts, the neck brace is a bitch, but not hearing from Jason is creating a desert. The beige bleaches every day.

I spend all my time after morning classes in the studio. I try to keep my pencil in my hand so I can’t hold the phone too. My new sketchbook is poster-sized, with a black cover. I only wear black jeans, black sweats, black T-shirts and a black City of Champions baseball hat, a parting gift from the boys. Charlie and Tom are usually the troublemakers. Stella was bewildered by the accident, by my abrupt departure, but instinctively she brought me a fresh white eraser from our school supplies drawer, ripped off the cellophane, and gave it to me to hold on to as I lifted my neck-braced self into the van. I keep the eraser in my other hand all the time now, squeezing its warm blanched skin. I search with my pencil for something, anything, in the blank screaming nothingness on the page.

I ran after him, slipping on the whiteness, but Dad caught me from behind, arms tight around my waist. He lifted me up, twisting me back, and I kicked at the air and got Mom in the hand. I hate you, I yelled, a siren in the wilderness. Dad pushed me in the gate and I broke away. I didn’t stop running until my door was locked.

Mom banged on my door. Where have you been? We were at the hospital. Babci had a stroke! I heard Stella crying. I tried to call, but you wouldn’t answer your phone! Silent as dust, I dropped to the floor. My dead cell phone fell out of my bag and slid under my bed. I willed myself not to move. A stroke. That meant paralysis. I made my limbs stay where they were. I ached for Jason’s warmth. I wonder if it hurts to have a stroke. Cramped, every muscle stabbed. My thoughts, twisted ropes; my heart, pounded flat; and my guts, shrink-wrapped. My ears were ringing. I wanted it to be Jason who was thinking of me.

My stunted windswept trees attract the attention of my teachers. Intriguing, they say. They’re looking for a tendril of root, a drop of water, a piece of grit. A pulse. The students are a mix of city and country kids here to have fun. Hey, everyone, we’re playing Twister in the dorm lounge tonight! I turn my body and braced neck the other way, pretending I can’t hear. They have no interest in me, or me in them. After drawing and painting all day, they want pizza parties, reality TV and loony board games. Every night, they’re all into being social, but all I do is check my phone. All I want is Hey, Babe.

I don’t care where the tears fall. I just smudge them away. Or not. I’m letting them buckle the smooth paper, for texture. Mom and Dad have been calling me every day. They go on about the boys and Stella, but I only listen to the news about Babci, who is still in the hospital. Weak. Sleeping. Not eating. They don’t tell me that, but that’s what I know from what they say. I dream about Babci. Her eyes are open, blue lights in a tunnel. I focus on the blue, and say nothing. I hang up when they talk about me. They’re also on the phone with the administration. Everyone is concerned about me. Everyone, except Jason.

My stunted, windswept trees attract my teachers’ attention. They’re looking for a pulse.

The stillness of the house that night, when I got up off the floor, startled me, and I wondered if I was somehow alone. In a scary new way, I was. I took my sketchbook and a can of cranberry juice, usually my favourite, but it burned road rash down my throat, ragged from yelling. I sipped it slowly to make it hurt more, trudging through the thin calm white to the hospital. It was still early morning. Babci’s room was dark, and I crouched in the window to catch the weak sun. There was nothing in the sky to break the blankness of it. Not a scribble of hope. So I started sketching her, leaving out the tubes and the breathing mask. I worked on the branching lines of her face. I sketched her eyes the way I remembered them, open and shining and bright. The light on her skin grew a little stronger with the break of day. Her breaths had no pattern, and more than once I stopped my pencil to listen. A nurse checked in. Her cheeriness exposed me, a hunched troll. Have we had a good night? Good girl! Lucky girl to have a visitor so early! I was in awe of this nurse, name-tagged Patsi, a chirping bird among the old and dying. She asked to see, so I showed her the sketch.

Your grandma is gorgeous! Lines on Patsi’s face dredged and deepened. I wish someone would do this for all of them! Patsi put both hands on my shoulders for a moment, and the two hills there melted into a prairie across my back. My mouth involuntarily nudged open. My throat was a raw fist, so I just nodded like a jack-in-the-box. She waited for it, my manufactured smile, and took it with her, to the next patient behind the curtain.

When I finished the portrait, Babci sighed. It took a long time for her next breath, and I wouldn’t breathe until she did. But I couldn’t wait that long, and I was sputtering and choking when Mom came in. She patted my back and handed me a tissue. My sketchbook dropped to the floor. She reached and picked it up, studying the sketch while I wiped away snot, spit and tears. I forced my voice until the growls morphed into words, I don’t hate you. Finally she said, I know. She looked at me from a new distance, eye to eye. We were on opposite cliffs now, but we’ll never take our eyes off each other. I wonder if Mom ever kicked and screamed at Babci. The way she adjusted the oxygen mask on Babci’s shrunken face, I knew, in her own way, she had. My hand shook as I ripped out the page, the last one in my sketchbook, and passed it. The purple bruises on the back of Mom’s hand pushed my stomach over the edge, and I went to find a washroom, and then a payphone to call Jason.

After two weeks of sitting alone in the camp cafeteria watching my food get cold and letting my tears salt the soup, a guy brings me soft ice cream from the industrial stainless dispenser, in a dish, swirls rooted and looped like filigree. He rubs a spoon on his shirt, taking his time to shine it up, and pokes it in the ice cream. I can’t look up at his face, but I notice his T-shirt. It’s black, with white writing: Eat me. Then it’s gone.

The next day, when I serve my own ice cream in a discreet simple twist, the guy builds a dramatic triple-decker in precise diminishing proportions and eats it, across from me, without a word. Hardly a look. And now every night, he and I meet at the ice cream machine, addicts, and sit down together. I feel a dandelion puff float across an emptiness. One day, the ice cream boy wears a red shirt with a stick-on retro nametag in red lettering: Hi, my name is Matt. I wonder why I never see him in class, unless he’s a janitor or a kitchen helper. His next T-shirt is black, with a fresh phototransfer of Michelangelo’s white marble David, and I get it.

Come to the studio? I can hardly nod my head with the neck brace, but I pick up my sketchbook and follow him to Sculpting. He turns on a battered CD player. It’s Bach. Strings. I like it. There’s purity, like finding feeling in my arms, shoulders, neck, where it once was numb. I feel a leaf flutter. He clears off a small table and finds me a chair. I take off the neck brace. He supports my back with his hoodie folded up into a cushion. Then he gets to work sanding his plaster. It’s white, like our vanilla ice cream. He’s sculpting a head. It takes me a while to recognize it’s mine.

Matt doesn’t talk much, and neither do I, but I follow him to Sculpting each night after supper. Sometimes, shudders suddenly shake out of me. My shoulders ease a bit. I stuff the neck brace to the back of the top shelf of my closet. I’m breathing deeper, like Matt, who gets a full-body workout every night chiselling and scraping and sanding. That’s after working the early morning shift at the gas station and going to sculpting class. No wonder he eats so much. I check out the Bach CDs on my way out one night, and the next day Matt gives me a freshly burned personalized one to keep.

I draw Matt sculpting. I make him a little more muscular than he is, and I write in some hidden messages for him in my pencil markings. Cool in his shirt pocket. Hot in his jeans. I title it, too: Matter. He makes me sign it, and points out how it’s ideal for a T-shirt phototransfer. I make a cardstock frame, the color of his eyes, spruce blue, like Babci’s, a hint for him to find a T-shirt that colour. He puts it up in the window by his workstation, which seems to be permanent. He’s the administrator’s nephew.

In the August heat wave, I start eating salads, but they’re as wilted as I am. Matt sticks to the fried food selections. We try to outdo each other at the ice cream machine. His are getting taller, architectural and turreted. Mine are like bonsai trees.

I feel every floating particle of air, every hair on my arm, every drop of sweat.

I’ve put on the weight I lost.

Your jeans fit better.

It’s all this ice cream.

Matt licks his spoon. I want to do you nude.

I laugh. It’s the first time I’ve opened my mouth wide all summer. I laugh and laugh and laugh, and everyone in the cafeteria is entertained. They laugh, too. I catch my tears on the back of my hand and whisper to Matt.

Why not? I haven’t got another answer.

We lock the studio and make sure the windows are covered.

If you jump me, I’ll stick you with sharp pencils. He pretends he doesn’t hear as I come out of the corner workstation with my sketchbook open, spine out at my waist, shielding all but my arms and legs. I got the black fuzz off. I creamed my skin, too. I slide one leg against the back of the other. I have to ask. Have you ever done a nude before?

Sure.

When?

Last summer. There was a girl. Like you. But she was fat.

Matt!

Static. She was static.

How long does it take?

About two weeks.

So how am I going to get my portfolio done?

I want you drawing.

Where do you want me?

Standing, at the drawing table. From the side. Put your sketchbook down.

I forgot my pencil.

Here’s one.

That’s not mine.

Your pencil is part of your hand.

My pencil is in my bag and I’m not bending over to get it.

I’ll get it.

Get the eraser, too. It’s white.

Get comfortable. I don’t want a pose.

Can’t you start with a clothed body and do the head first?

I’ve already done the head.

Can I put my jeans on? Can you do the top half first?

I need to work with the whole form.

I need a drink.

Water. He brings me a bottle, cold, slippery with condensation, and twists it open. Anything else?

You can’t touch me.

I stay behind this line. With a dry paintbrush, he draws a semicircle in the dust on the black floor about two metres away from me. Does that work for you?

I can’t work if you talk to me.

I can’t either.

I want the cello prelude in D.

I was thinking of something slower.

I want the volume up. Way up.

What about the fan?

No.

It’s sweltering.

Not when you’re wearing a sketchbook.

Later?

Maybe.

Just put it down, and draw.

I want to run, but I don’t want to show my back.

Matt says, You’re a deer in the woods. Eating leaves. You don’t see me.

You’re going to shoot me.

I’m a photographer. I’m doing a photo essay on deer.

Why?

Blame Bach.

What for?

For grace. Deer are full of grace.

And I put down my book, and draw. I make him repeat the deer talk every night, and every night I draw trees. The heat gets worse, especially with the windows always closed now, and I let him turn on the fan. When he does, I feel every floating particle of air, every hair on my arm, every drop of sweat on the back of my neck, under the loose braid of hair that is the only part of my costume. My trees become fuller, less ragged. They have tiny individual leaves. The leaves grow in proportion and in number every night. On the paper is a jungle of branches and bark and new leaves, each shape revealing another and another. I try not to look at the rough plaster column. I stay in the woods. I breathe in the dust Matt makes with his tools and his strokes, and when the music stops, the sound of his hand sanding, sanding, sanding blends with the motion of the fan. At the end of each session, he drapes the sculpture before I can put on my robe and look. It’s about a quarter of my size, but its mass is startling.

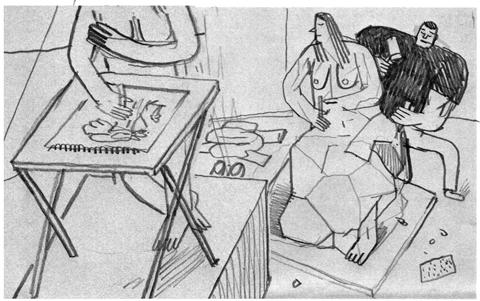

Illustration by Josh Hollinaty.

Does it have a title? Or is it Nude Two?

Nude Two.

But tonight, after I’m dressed, he pops a mini-champagne that his boss, who is in AA, slipped to him after winning it at a golf tournament. Matt unveils her and we drink, from clear plastic cups, to Nude Two. She doesn’t look a lot like me, or anybody. I make out the braid, but she’s faceless, all smooth muscle, fired and working, culminating in the tip of the pencil in her left hand.

How was Nude One like me?

She was sad.

And did she get happier?

That was Bach.

You’re going to be great.

Bach is great.

Keep in touch.

Hey, Babe.

So I hug him. I let him ride his hand up my back, under my shirt. I let him feel my arms, my neck, and unbraid my hair. He runs his hands down my thighs and up again. He’s getting red in the face, but I sip my bubbly like it’s 7-Up. His hands need to know. Then I kiss him on the lips, just once, because he should know what that feels like too. Then I kiss Nude Two, on the top of her intent little head. I recognize the tilt of it. She’s alive, I say. But I’m thinking of Babci. Matt watches me gather my drawings, my sketchbook, my robe and my pencils, and I enjoy it. I go to my room to pack. The show is tomorrow, and then I’m going home.

Katherine Koller is a playwright and teaches at the University of Alberta. “Art Lessons” is her first published fiction.