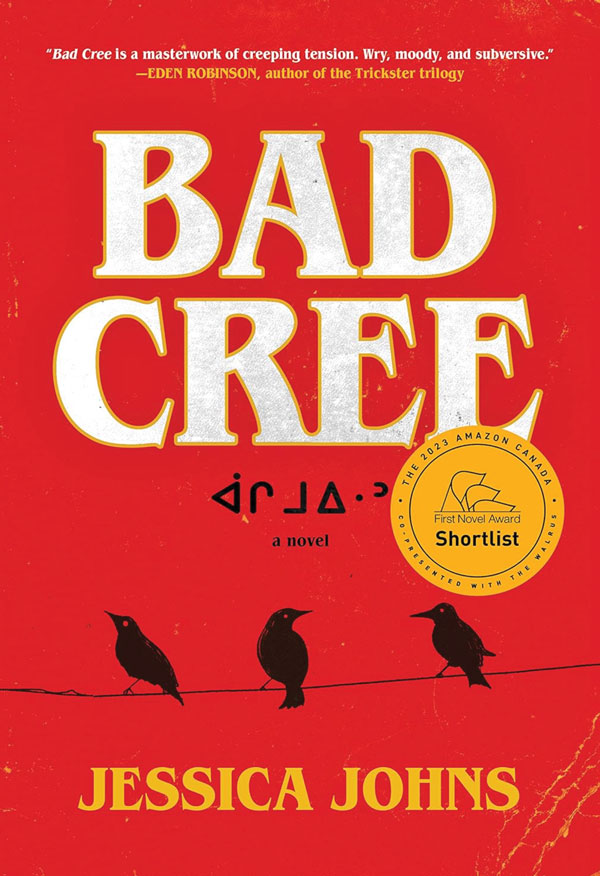

A coming home narrative wrapped in horror, grief and dreams, Bad Cree is a captivating debut by Jessica Johns. Johns is a member of Sucker Creek First Nation who won the 2020 Writers’ Trust Journey Prize for a short story—also called “Bad Cree”—which she expanded into this novel. The book is both terrifying and heartwarming, with protagonist Mackenzie plagued by gruesome dreams, and seeking out fierce and hilarious matriarchs to help unravel the mysteries of her very real nightmares. They assist in various ways: early on Mackenzie phones one of her aunties, who is in the middle of a “ten-thousand-dollar dual dab” bingo night. On a smoke break she calls Mackenzie back. After listening to her dreams, she says, “My girl, I might be an old Indian, but I’m not a goddamn dream oracle.” Good medicine like this is sprinkled throughout.

Mackenzie is torn by guilt about her sister’s death, and the novel follows her journey home from the Pacific coast to the prairies, from Burnaby to High Prairie. It’s a setting I responded to. As someone who grew up without reading or seeing much representation of places such as Edmonton in popular culture or in the classroom, I spent my adolescence dreaming of moving away to Vancouver. But maybe I wanted, as Johns succinctly writes, to “just leave the bad behind.” The bad being grief.

I could imagine myself anywhere from age 13 to my early 20s appreciating the horrors of Bad Cree but desperately needing to hear the life lessons it contains. While there are some grisly dreams—and the whisperings of evil creatures that some nêhiyawak would prefer not to name—the subtle teachings on grief and the importance of family are beautifully composed.

The novel also presents a refreshing representation of some of the contemporary issues that urban Indigenous peoples experience today, from Mackenzie’s non-binary kin in the city to the repeated use of checking one’s shared locations. It’s relatable, and yet each character has their own unique rhythm and way of being that kept pulling me in to learn more.

Later in Mackenzie’s quest for insight into her nightmares she searches online for dream knowledge, finding vague answers from Reiki healers to dissertation papers, before realizing: “Why am I searching for my answers somewhere else?” She understands she doesn’t need the internet to learn what her family must already know. All she has to do is move past the fear of having her family worry about her—give up control and become more vulnerable in her search for help and guidance.

But it isn’t so simple. The grief in this novel is both a haunting and a place for intergenerational healing. We might run away from grief, but it can also guide us in finding our way home.

Kaitlyn Purcell is a Ph.D. candidate at the U of C.

_______________________________________