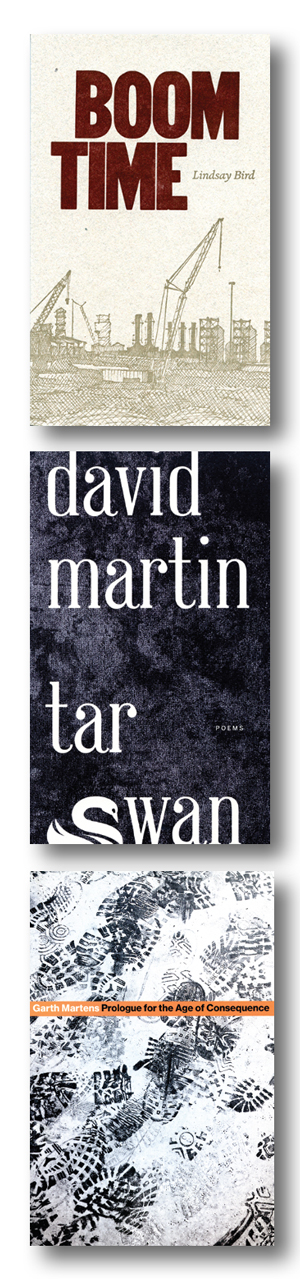

Boom Time

by Lindsay Bird

Gaspereau Press

2019/$19.95/96 pp.

Tar Swan

by David Martin

NeWest press

2018/$19.95/96 pp.

Prologue for the Age of Consequence

by Garth Martens

House of Anansi Press

2014/$19.95/120 pp.

Garth Martens’s debut performance, in his 2014 book Prologue for the Age of Consequence, set a poetic template, hammered together with a framer’s hammer and a carpenter’s level, for writing about construction work in general and the Alberta “tar sands” in particular.

In the poem “Leathering,” he writes:

He forgets his reasons, his debts, his wife,

works a ditch or drives a spike.

There is a stone in his wrist.

… If he could reach, he’d pull

every twisted star with a hammer.

The poem sums up both the pride and the anger of tradesmen and labourers forced by necessity to engage with an abysmal human project known simply as “the tower,” a brooding monstrosity whose purpose is never explained to the workers.

The tower is an industrial altar that requires constant sacrifices of tears, sweat and blood. Workers have come from all over Canada, indeed all over the world to carve out a piece of bituminous booty, and Martens introduces a compelling multicultural cast of troubled souls, led by a Bunyanesque character, the foreman Johnny Lightning.

But this is not really docu-poetry about work. Martens is a schooled writer who unleashes a rich Cormac McCarthy-like fusillade of nouns and adjectives arcane enough to make Rex Murphy swoon in admiration, or topple Conrad Black from atop his thesaurus.

Martens creates his own blue-collar mythology, which often springs from the hallucinogenic effects of exhaustion, due to brutal work, tight schedules and the inhalation of numerous industrial toxins. Prologue for the Age of Consequence is truly a tough act to follow.

Martens’s tar sands is very much a male-dominated and male-destroyed landscape. In Boom Time, Lindsay Bird presents the distaff side of the songbook, based on her experience in isolated northern work camps. She is more about the human interactions in the camps, rather than the muscular heroics of the workers, but she is no fan of the corporate ethos either.

Her poem “All I Have to Say About Calgary” dismisses the oil slick HQ in 10 words:

What a good place

to buy a pair of shoes.

In “The Meal Hall” she deals with male misogyny with similar efficiency sans feminist exhortation:

“Hey, sugartits // Sugar/ tits?/ Now/ I’m dessert/ too. Who/ knew?”

But she can break hearts with a prose poem like “Garland,” about a 56-year-old worker, proud and pleased to have “this good job out west” driving a delivery truck for the mine. It’s all over in a flash when he’s asked to read a safety reminder aloud: Garland can’t read, and in a jingle of surrendered keys, he’s out the door. “…I can’t tell you,” writes Bird, “if it was his chest shaking behind the steering wheel, or the heavy haulers moving the earth all around him.”

In Tar Swan, David Martin eschews the realities of labouring and dives straight into mythology, also of his own creating. What he has in common with Martens is a density of word play, but here there is no real hinge to hang the poetry on except a few facts—that one man, Robert C. Fitzsimmons, was the first to build an oil sands separation plant, and another, Frank Badur, a mechanic, is accused of sabotaging the works. Then there is Dr. Brian K. Wolksy, an archaeologist exhuming the colonial and Indigenous histories of the plant. As for the eponymous tar swan, it’s a fictional creation that seems to function as the primal voice of the land itself, although several references to Greek myth are less than convincing in this context.

I say seems, because nothing is really clear in Tar Swan or in any of the four voices the poet employs except the gradual descent into madness of the poisoned protagonists, Fitzsimmons and Badura, under the malevolent influence of the tar swan persona.

This is experimental poetry, language poetry in this case, which depends on the reader to bring her own interpretation to the text. For example, this from page 31:

Gentlemen, Sunday surrender body whims and

shilly-shally Yourselves with a harvest of plate colour.

The text ends, after a seven-line ramble of synecdoches and metonyms, with:

… Set the

watch to tattoo, for tomorrow is tomorrow and tide

is tiding again.

You will have to take my word for it when I say that those of us who love verbal fireworks will be swept along in the Athabascan currents of Tar Swan, albeit to a fraught conclusion.

Writers of experimental verse sometimes fly so high they go right out of sight, or at least out of sense. This book is a wild ride, chilling at times though leavened with dark humour, and the poet has an ominous warning for politicians and taxpayers to come:

…yoU’ll never oUtbreak what we’ve

Unearthed. YoU’ll never be free of my UndertOw.

—Sid Marty writes prose, poetry and music at the foot of the Livingstone Range in southwestern Alberta.