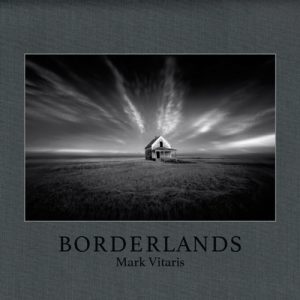

by Mark Vitaris

Frontenac House

2020/$60.00/192 pp.

If a photograph only captures reality for, let’s say, 1/500th of a second, how can it represent history? That’s the challenge of Borderlands, a new black-and-white collection from Calgary photographer Mark Vitaris. It’s set along the 49th parallel, from the eastern Rockies in Alberta and Montana to the Saskatchewan grasslands and western North Dakota. Sediment deposits formed this landscape 85 million years ago, and 15 millenia have passed since runoff from the Laurentide ice sheet carved the canyons seen today. In the 19th century, colonization transformed the region into a commercial and strategic hub, and traditional life vanished just as quickly when the buffalo were killed and railway track was stitched across a new nation. It seems impossible to show all at once, but Vitaris is undaunted.

He calls Borderlands a “photographic discourse,” interwoven with anecdotes, poetry and the history of colonization. “During five years of criss-crossing the borderlands,” he writes, “I have driven roads to experience and photograph this incomparable landscape and have eaten dust to understand it.” Readers—viewers—of this book can taste it too. In Gold Butte, Vitaris reads a gravestone of a teenage girl who died from tuberculosis. He shows us Shelby, a Montana boomtown doomed to disaster. We visit places with names like Pinto Horse Butte, sit in the shadows of hoodoos and lopsided barns and see crumbling motels, pockmarked seed elevators, long-lonely playgrounds and the husks of hollowed-out homesteads.

Fans of black-and-white Western photography might recall John Smart, who documents some of these very landscapes, or even Ansel Adams. But Borderlands is all its own, because Vitaris’s real subject isn’t place but time. In Saskatchewan’s Grasslands National Park, he traces the steps of a Sioux woman escaping the US Army. He ponders “the transformational nature of time created by this seemingly unchanged land” and “the temporal quality of human endeavour in the enduring Prairie landscape.” This is the true border of Borderlands: not the 49th parallel but the one “between then and now.”

Vitaris portrays this by rendering disappearance visible. He’s not shooting the old Chevy, per se—he’s photographing the degradation that time has wrought on its rusting, crumpled frame. He compels us to ask why some things haven’t disappeared, such as a pair of bifocals left behind on a deserted kitchen table, or an auto service station in Mankota that might or might not be abandoned. The tension between what’s gone and what’s left is the central drama in Vitaris’s powerful photographs. Only when you “see” what’s disappeared from this land can you begin to understand it.

—Robbie Jeffrey is a freelance writer in Edmonton.