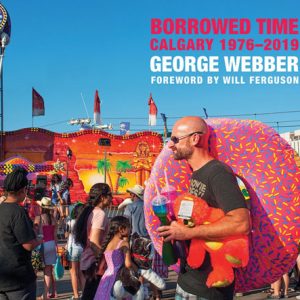

by George Webber,

foreword by Will Ferguson

Rocky Mountain Books

2021/$50.00/208 pp.

All things must pass, George Harrison reminded us 50 years ago, and in Calgary that’s what they do. Here the barely old—neighbourhood confectioneries, low-rise apartment buildings with names like “The Maureen” curlicued in black on their sides—quickly disappears. And the people? The city, all road construction and three-quarters-empty office buildings, wants them to hurry up and be someone else. We don’t need no union brewery workers. We don’t need no denizens of welfare hotels. Pretty soon we won’t need no geologists. If there’s one place where getting over yourself is a necessity, it’s Calgary.

George Webber has been monitoring Calgary’s recurrent death and resurrection in photographs for more than 40 years. His latest book from his long-time publisher Rocky Mountain Books has the air of a retrospective exhibition, but one for which most of the artist’s best-known pieces were unavailable. Borrowed Time has a lot of photos that look like they had their origins in newspaper or magazine photo-essays, or in book projects for which they didn’t quite make the cut. That makes it sound like this isn’t Webber’s best work, but that’s not the case. These photos are recognizably Webber—lots of attention to blank space and making the corners of the image interesting, lighting that seems to emanate, somehow, from inside the subjects, and, for a lot of the outdoor shots, a dedication to capturing the gorgeous Alberta skyscape.

Webber’s best-known Calgary work, Last Call, a look at the inhabitants of three inner-city hotels slated for destruction, casts a shadow over this latest collection. It’s easy to take, for example, his portraits of tenants at Murdoch Manor and the Midfield Mobile Home Park as just more nostalgie de la boue from a guy who makes a living out of it. And the cynical part of me thinks that’s not entirely wrong. But beyond that, Webber shows a respect for his subjects both as people whose lives have meaning and, also, as figures of beauty. You might feel a little manipulated when you look at a George Webber portrait, but you don’t feel as if you’re slumming or intruding.

Attention to the beauty in the humble is also the hallmark of Webber’s photos of buildings, signs and other man-made objects. For me, these are the best of Webber’s work, because the things we make are far easier to divide into the aesthetically pleasing and the won’t-be-missed than people. Webber juxtaposes graffiti, old vending machines and purely functional architecture against the sky, the slush and the rough city flora. He revels in their lines and roundness. He shows how they can be beautiful, how we can be beautiful, even in a town that often only sees our uselessness.

Alex Rettie is a long-time reviewer for Alberta Views.

_______________________________________