Few people on the planet would suggest that Lethbridge has anything in common with Bilbao, Spain. Lethbridge is a town where the prairies sigh under the weight of yet another Wal-Mart squatting on farmland; Bilbao is home to one of the world’s most impressive art museums, where about 10 million visitors have pumped billions into the local economy over the past decade. Lethbridge’s downtown is dotted with vacant lots, pickup trucks and rows of empty storefront real estate; Bilbao has a fascinating array of public transportation options and a cobblestone-lined, pedestrian-only old city core. Lethbridge has just completed its first public sculpture commission for the downtown; Bilbao is filled with interesting public art.

Bilbao used to be a European version of the US rustbelt, a city built around an industrial economy in decline. In 1997, the Guggenheim Foundation—along with about $100-million from the Basque regional government—opened an art museum that transformed the economy of the entire region. Canadian-born architect Frank Gehry designed the massive gallery, which has since spawned its own catchphrase: “The Bilbao Effect,” the enormous growth potential of a regional economy based around public investment in the arts. The Guggenheim’s first decade brought Bilbao at least 4,500 jobs and $400-million in additional tax revenue to the regional government.

Lethbridge and Bilbao differ in one additional respect. No one in Bilbao had several million dollars’ worth of contemporary art sitting around waiting to be displayed. Lethbridge does. The story of how it got there, and why it remains relatively inaccessible, showcases the contradictions of Alberta: a place where striving for collective excellence is consistently thwarted by the straitjacket of market fundamentalism—the fashion of choice for the provincial body politic.

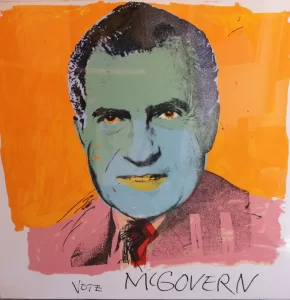

Lethbridge is the last place one would expect to find a Picasso, a whole set of sketches by Henri Matisse or an original silkscreen of Andy Warhol’s “Mao.” But they are here—along with Jean Dubuffet, Roy Lichtenstein, Patrick Caulfield, Peter Blake and Jenny Holzer. The giants of the contemporary art world slumber in a climate-controlled vault on the west bank of the Oldman River at the University of Lethbridge.

There’s an impressive array of First Nations and Inuit painting, sculpture and carving: Norval Morrisseau, Mungo Martin, Robert Boyer and Winnie Tatya among them. The “big names” of Canadian art are the focus of the collection—the Group of Seven and Emily Carr, yes, but there’s also careful representation of modern-art stars like Jean Paul Riopelle. The collection’s strengths are in Canadian contemporary, landscape and Anglo-American pop art. There’s also sculpture, photos and artifacts from curious origins, from Roloff Beny’s photographs of the last Shah of Iran to spears from Papua New Guinea.

With 13,000 objects, the U of L art collection is one of the largest in Canada, worth an estimated $34-million. Only the Art Gallery of Ontario and the National Gallery have more Canadian and US contemporary works; only a handful of universities, such as Toronto, McMaster and Carleton, can compete with the U of L collection’s depth as a teaching resource. Whatever the measure, the consensus in the art world is that Lethbridge stores one of North America’s most significant cultural heritage treasures.

Visitors to the university can see the collection in one of two public exhibit spaces. One is the hallway connecting the library and the arts building, beside a coffee kiosk. The other space, a gallery, is about the size of a university classroom. The workspace for researchers, students and curators is about the same size.

Including the hallway exhibits—with space for about 50 works—and the small gallery and workspace, the U of L art collection gets about 3,000 square feet of public real estate. The rest of the collection is carefully stored in a vault. There is no space for exhibiting the contents of the vault. And no plan for any.

Jeffrey Spalding is the new president and CEO of Calgary’s Glenbow Museum. Spalding has spent his career curating art collections in Calgary, Nova Scotia, Florida—and Lethbridge. Spalding moved to Lethbridge in 1981 to become the U of L art gallery’s first director. He was hired on a one-year contract; he stayed 17 years.

He says the U of L collection has three roots. A small but finely crafted ensemble of works collected by dean of arts Bill McCarroll in the 1970s allowed the art department to become serious about collection. Throughout the 1980s, a provincial arts funding scheme guaranteed the university matching government cash for every dollar’s worth of art donated to the U of L—which encouraged ongoing acquisitions.

Spalding argues that the “richness” of the collection “merits a dignified treatment—a decade-by-decade walk through Canadian contemporary art and First Nations/Inuit art. Like something you would see at the Art Gallery of Ontario or the National Gallery.”

The collection’s current size can be traced to a shopping trip in 1981. McCarroll and Spalding visited galleries across the country, looking to spend a few thousand dollars on eight or nine pieces of British pop art. After “bothering every important dealer in the country,” the Lethbridge crew settled on only one much more expensive work by Patrick Caulfield. Though they didn’t buy from all those “important” dealers they had visited, the word was out that a small, new university in Alberta was building a collection of art for the purpose of teaching undergraduates. By the time Spalding got back to Lethbridge, he’d secured a donation of 350 pieces of contemporary American and Canadian art. That first major gift remains anonymous, but donations persisted. Spalding says living artists began donating work, making the collection “its own machine.”

“We were interested in showing someone’s development, with sketches, drawings or written work,” he says. “Seeing that is very empowering to students.” Spalding says the collection was always about the students, and that the department had a “crisis” on its hands previously. “You cannot teach art without allowing students to interact with art. You would never teach English without giving people books to read. This is the same.”

“We had to, in some way or another, increase the ability of our students to see important, pertinent art objects,” he says. “We weren’t just out there with a trawler taking anything and everything. We looked for things to complement the standard texts of the day. The collection is meant for teaching. It is meant for understanding an artist’s process, for understanding history, as well, through art.”

U of L art students are able to view items in the collection on request. Students rely on their professors to take them to visit items from the collection as coursework, or recommend certain artists to look up; some professors include collection materials in coursework and some don’t. Some art students benefit tremendously. Others have only a vague notion of its existence.

The public’s access is more restricted—typically, they are not allowed to visit the vault. According to current gallery director Josephine Mills, about 2 per cent of the collection is on display at any one time.

It’s a limited role for a collection that could draw visitors from across the continent. Spalding says the limited audience—even on the U of L campus, let alone the wider Alberta public—means “the university has an unfinished responsibility to students, faculty, southern Alberta and Canadian heritage.”

There’s no shortage of effusive praise for the art collection. The university touts the collection in many of its marketing and student recruitment materials. Art students are regularly reminded of its significance; politicians hitch their wagon to the collection when it’s time for a little civic boosterism.

“We have a tremendous collection here, and right now it is basically hidden away at the university. It is a very important part of this community,” says Clint Dunford, former Conservative MLA for Lethbridge-West and a cabinet minister in the Klein government. Dunford does not hesitate to put a fine point on the potential economic benefits of a new gallery for the U of L collection. “This is really an opportunity for the citizens of southwestern Alberta… and the business community. They really stand to benefit from the economic diversification that could come from this.”

“The collection is spectacular,” adds U of L president Bill Cade. “I would be proud and delighted to have a new gallery to show it. Who would be against that?”

Everybody has something nice to say about the U of L art collection. Nobody is serious about finding the cash for a gallery.

Jeffrey Spalding says the university needs to show leadership on the issue, and that the region needs to make a united pitch to the city, province and federal governments for money.

Clint Dunford says government responds to what universities request, and that the university has never seriously asked for provincial investment in a new art gallery.

Bill Cade says the province won’t fund projects that don’t create new classroom spaces. There’s no point in putting the art gallery at the top of the capital plan; the province won’t fund it.

All roads lead to the province, and the province, at least in the university’s view, is a dead end. The university’s default strategy is to wait for the tooth fairy. “We’re really holding out hope for an angel donor,” says Cade, adding that a smallish gallery would cost “in the neighbourhood of $30-million.”

“There are individuals accumulating enormous wealth in this province, and a lot of them love art. It will happen eventually.”

Nineteen years ago, an angel did descend upon the U of L, but was sent packing by the university and the province. The owner of the old Eaton’s building downtown, explains Spalding, gifted the former department store building to the university for the purpose of showing the collection. In the summer of 1989, citizens of Lethbridge could tour a number of galleries covering 50,000 square feet in total. There were four main wings: Canadian historical art from 1770 to 1950, Inuit and Native American art since 1945, a New Guinea exhibit and the art of Western Canada from 1960 to the 1980s.

Entitled Bridge, the Eaton’s exhibit brought the collection and the university national acclaim and over 4,000 visitors. The university and the province, however, were unmoved. The U of L president at the time, Howard Tennant, refused the donated building, indicating that an art gallery wasn’t the university’s responsibility. The province was equally dismissive. “We’re in the business of educating,” Advanced Education Minister John Gogo told The Globe and Mail, “not funding art galleries.”

And so, in September 1989, the art was packed up, toted back across the river to the university and stored away. The Eaton’s building was demolished, and a nondescript bank took its place. Across the street, empty commercial real estate dominates the block.

The Eaton’s debacle remains a wound in the community. The university’s view is that the collection should remain on campus—a gallery on the west side of the river is the only option current president Bill Cade says he will entertain for the collection. Others, including members of the business community and some civic politicians, believe the collection should be showcased downtown as a way to revitalize the Lethbridge core.

Dunford acknowledges that the province took a tough stand on university and arts funding in the past, but he says the Tories have had an attitude adjustment recently.

“A request for capital funds for an art gallery would be met more favourably by caucus now,” he says. “Times have changed. When Ralph and I and others first came in [in 1993], we were—rightly or wrongly—really focused on reducing deficits and debt. But now there are huge surpluses… more revenue that could be directed toward arts and culture. At the last caucus retreat [in 2007], we had a representative of the arts community making a presentation. That has not happened in my 14 years in this Conservative government.”

Dunford says it is up to the U of L to ask for the money, and they haven’t done that yet. He adds that the government cannot—and should not—dictate university priorities.

But the province doesn’t have to dictate university priorities. Instead, Alberta, like the rest of Canada, has engineered a university funding structure where priorities are set by the marketplace.

In 1994, 74 per cent of Alberta university income came from government. Today, government grants account for 58 per cent of university revenues. A mix of outside dollars and tuition increases makes up the shortfall.

Behind annual tuition headlines, though, is a subtler story. The operating grants that used to account for three quarters of university funding used to be mostly comprised of unrestricted grants, in that they simply went into a general pot of money that the institution then used to fund its operations. But now, much more of that grant money comes with strings attached. In 1998, 8 per cent of the U of L’s operating grant came from sponsored research; in 2007, it was 20 per cent. And so the university not only gets a smaller pot of public money, but there are many more restrictions on how they can spend the money they do have.

Attracting sponsored research is a national competition, and it’s up to university administrators to ensure that the institution’s efforts are focused on that money trail. Most often funded by Ottawa’s science and health foundations (not directly by corporations), sponsored research is often tied to developing marketable, patentable products or discoveries. Funding agencies like NSERC and the Canadian Foundation for Innovation and provincial outfits like Alberta Ingenuity often tie their research awards to private-sector matching funds or private-sector interest.

Sponsored research dollars are disproportionately directed toward biotechnology, engineering, business and health sciences. When it comes to the big dollars, art isn’t part of the mix.

In the race for sponsored research, a university’s building priorities—investments still largely the provincial taxpayer’s responsibility—are whatever will attract outside money. Over the past few years, the U of L has requested provincial cash for water research, neuroscience, the faculty of management, physical education and health sciences buildings. Now that the province has funded those requests, attention is turning to the faculty of science. The art gallery is on the capital plan, but that’s not enough to get it funded. If the project isn’t at the top of the university’s priorities, it is a mere wish-list item, waiting, in the words of president Cade, for an angel.

Current U of L Art Gallery director Josephine Mills does not agree with the suggestion that the collection is languishing in a vault, locked away from public view. She agrees with the widely held view that the university should invest in a new space for the permanent collection. But that’s where her criticism stops.

“We make the most of the space we have,” says Mills, noting that a publications program and online presence create a virtual space in order to compensate for a lack of physical facilities. “We loan to galleries across the country—the Vancouver Art Gallery, Nova Scotia Art Gallery. We send works on touring exhibits. We facilitate research. Even if we had a bigger space, we would continue with those partnerships.” Mills downplays the size requirements for a new gallery. “We would be happy with something about double what we have now,” she says.

Spalding argues that the “richness” of the collection “merits a dignified treatment—a decade-by-decade walk through Canadian contemporary art and First Nations/Inuit art. Like something you would see at the Art Gallery of Ontario or the National Gallery.”

With 13,000 objects, the U of L art collection is one of the largest in Canada, worth an estimated $34-million. Only the Art Gallery of Ontario and the National Gallery have more Canadian and US contemporary works.

Mills isn’t thinking that big. “We’re looking at models like Kelowna, Kamloops and Moose Jaw. Otherwise it’s too expensive to run.”

Jon Oxley is in his second decade at the U of L. He was SU president during the squabble over the Eaton’s building and worked for five years with the art collection, cataloguing, photographing and moving it to the legendary “vault.” Oxley is now general manager of the SU. He’s seen the university change considerably as it conforms to the fiscal discipline imposed by the province. But Oxley says it isn’t up to any one body—especially the university alone—to build an art gallery.

“The university has a responsibility to take care of the collection,” he says. “It is up to the collective body politic to make sure the public has access to it. The art collection is an example of excellence—but the way it’s been handled, it is almost as if people are ashamed of it. They wouldn’t be ashamed of a similar level of excellence if it was in a field such as engineering.”

The U of L collection may well—someday soon—have a home in a small university gallery, with enough space to properly curate shows, do research and teach students. But it won’t be because our collective institutions decided that the collection is an important part of Canadian heritage; if the U of L ever gets a gallery, it will likely be because it waited for a private individual to make it so. Public institutions have internalized the privatization ethic to the point where they are passive recipients of private-sector benevolence rather than leading the charge for creative, vibrant communities. It makes for a strange kind of passivity in a culture that purports to have a gritty, entrepreneurial, go-getter ethic.

To excel at university administration these days is to internalize privatization’s golden rule: public institutions—effectively the expression of our collective will—should not do anything that doesn’t directly deliver silver-platter profits to the private sector. If funds magically appear for other priorities—such as an art gallery—then so be it, but the university is monumentally uninterested in leading any effort to bring various levels of government together for the sake of an art collection. Despite some upward adjustment in university operating grants and a loosening of the financial noose that kept Alberta’s universities on the brink of financial annihilation in the 1990s, the transition to corporatized, research-intensive, science-and-engineering, prestige-oriented institutions of higher learning is complete. Art, in today’s university, remains a frilly add-on.

Lethbridge may just be another big-box town on the outside—a place you’d never expect to compete with the chic art scenes of big cities. But to insiders, Lethbridge is a progressive place where art openings attract hundreds and working artists convert downtown lofts into utilitarian studios; a place where the city funds public art and invests in its downtown green spaces—making Lethbridge one of Canada’s most interesting small cities. The unfinished responsibility is to pool those collective efforts to become the arts and culture jewel of the prairies. If the right people dared, Lethbridge could even be one of the cultural must-sees of the continent. With just a little more audacity, Alberta could have its own version of Bilbao. #

Shannon Phillips is an independent journalist based in Lethbridge. She also writes for the Parkland Post and Vue Weekly.