On February 8, 2021, after months of growing concern among Albertans at the thought of a half-dozen new coal mines in the headwaters of south-central Alberta’s rivers, Energy Minister Sonya Savage announced that the government had rescinded its rescindment of the province’s 1976 Coal Development Policy. “We admit we didn’t get this one right,” she said, in the biggest understatement since former premier Ralph Klein admitted he had no plan to address out-of-control oil sands development. “We’re not perfect and Albertans sure let us know that.”

Minister Savage and Premier Jason Kenney obviously underestimated the wrath of the Downstreamers. While there are many valid reasons to be concerned about coal mines in Alberta’s Eastern Slopes, the primary one seems to be the health and cleanliness of the streams and rivers that flow out of the Rocky Mountains through rolling ranchlands and the increasingly crowded exurbs, suburbs and urban areas of Edmonton, Red Deer and Calgary. Local alt-country music sensation Corb Lund summed it up best: “I know there’s always two stories, and there’s always different values to balance. But I gave it my best shot, and I took in all the information for weeks and studied it. And I got to tell you, I’m kind of pissed off.”

He’s not alone. The new Protect Alberta’s Rockies and Headwaters (PARH) Facebook group grew to more than 35,000 members, 10 times more supporters than various Alberta-based “Stop the Tar Sands” groups. These PARH groupies responded to Minister Savage’s announcement with a flurry of heart and thumbs-up emojis as Alberta’s growing anti-coal movement rejoiced. A few days later, however, when the smoke had cleared and the twin blinders of euphoria and optimism had worn off, it became crystal clear that the return of the coal policy and the promise of future public consultation would do little to halt the revival of coal mining on a massive scale in Alberta’s sublime southern Rockies.

“Cancel all exploration permits and revoke all leases on the Eastern Slopes,” posts David Patterson every chance he gets. Patterson, a former engineer with Syncrude Canada, lives in Edmonton, some 300 km downstream of the Obed Mountain, Coal Valley and Vista coal mines near Hinton. “Anything else is just a BS con game.”

PARH has several seasoned veterans in its ranks, including a former Banff National Park superintendent, a few current or former professional environmentalists and a couple of biologists that used to work for the provincial government, but it’s obvious many of its members are brand new to the deadly serious game of environmental politics. Despite living in a democracy that often acts like a wholly owned subsidiary of the fossil fuel industry, these folks are totally unfamiliar with the laws and regulations that determine whether and how industrial projects are allowed to proceed, never mind the history of overly discretionary policy processes that have allowed unchecked industrial development to spread like a cancer across our public lands. For some, it has come as quite a shock to learn that the politicians they voted for in the last election—politicians who campaigned on expanding the already toxic and destructive oil sands—would allow foreign-owned coal companies to set up shop in the mountains they can see from their doorsteps.

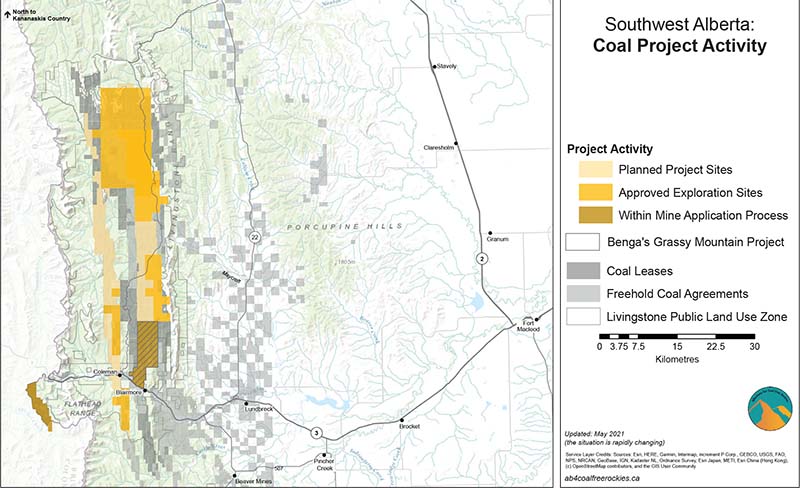

Few of the PARH groupies, for example, were even aware that the owners of the proposed Grassy Mountain (photo p 27) coal mine, 7 km north of Blairmore in the Crowsnest Pass, had applied for a mining permit six years ago, during the NDP’s tenure in power, and have been building roads and drilling exploratory boreholes ever since. Ranked #6 on Mining magazine’s “Top 10 Mining Projects to watch in 2021,” Grassy Mountain is proposed by Benga Mining Ltd., a wholly owned subsidiary of Riversdale Resources, an Australian company. Benga/Riversdale proposes to remove the top 430 metres of Grassy Mountain and extract some 93 million tonnes of metallurgical coal over 23 years, bringing with it “much-needed foreign investment to the Canadian economy along with the creation of hundreds of jobs in Alberta.”

Grassy Mountain is the test case in the UCP government’s Black New Deal with the coal industry, and it’s already in the final stage of a multi-year environmental impact assessment. Although conducted on behalf of both the Alberta Energy Regulator (AER) and the Impact Assessment Agency of Canada, the joint review is basically run by and for the AER, an industry-funded agency responsible for regulating oil and gas activity and coal mining in Alberta. The AER has frequently been criticized for failing to provide adequate oversight.

The Grassy Mountain environmental impact assessment is overseen by a three-member joint review panel chaired by Alex Bolton. Bolton, the AER’s chief hearing commissioner, like most hearing commissioners, has a long history regulating or working for the drillers and diggers of fossil fuels. Having chaired the joint review panel for Teck’s Frontier oil sands mine and been a member of the panel that assessed Shell Canada’s Jackpine oil sands mine, Bolton knows more than a thing or two about the social and environmental impacts associated with giant industrial energy projects. If there is an Alberta-trained master at this game, Bolton is it.

Despite constant claims that Alberta has a “world-class regulatory regime,” environmental protection in this province is weak, which may be why we don’t have our own environmental impact assessment legislation. The provincial Environmental Protection and Enhancement Act does include an “environmental assessment process” to evaluate “plans to mitigate any adverse impacts from the proposed activity,” but it’s worded in such a way that it doesn’t interfere with our Coal Conservation Act (or our Oil Sands Conservation Act), the purpose of which is “to ensure orderly, efficient and economic development of Alberta’s coal [or oil sands] resources in the public interest.” In short: The starting point of AER hearings is that coal mines are de facto in the public interest.

Thankfully for those Albertans opposed to new coal mines, the federal government has the ability and arguably the obligation to wield a bigger and better stick on behalf of those who care about, say, clean water and the recovery of species at risk. It was known as the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act, 2012, recently replaced by the Liberals’ new Impact Assessment Act, 2019, which Alberta Premier Jason Kenney has asked a court to denounce as unconstitutional to prevent the feds from interfering in his plans for the coal industry.

The main purpose of both the former Canadian Environmental Assessment Act and the current Impact Assessment Act was and is “to protect the components of the environment… that are within the legislative authority of Parliament [things like threatened and endangered fish species and the habitat they depend on] from significant adverse environmental effects caused by a designated project,” followed closely by an obligation to “ensure that designated projects… are considered in a careful and precautionary manner to avoid significant adverse environmental effects.”

With such an experienced joint review panel chair and the strong arm of the federal Species at Risk Act (SARA), what could possibly go wrong?

The lengthy drama of formal environmental impact assessment in Canada has three acts. Act I involves a company proposing a “designated project” and hiring an army of consultants to assess the project’s potential adverse environmental effects. In the case of Grassy Mountain, Riversdale (in Canada, Benga Mining operates as Riversdale) submitted an environmental impact statement of thousands of pages in August 2016, along with applications for the permits it would need from federal and provincial government agencies to build the mine. These company-generated analyses are notorious for being overly optimistic and grossly incomplete, and Riversdale did not disappoint.

Of the 162 identified possible negative effects on everything from old-growth forests and wildlife to air and surface water quality, apparently not a single one would be significant. The impact statement proposed that any and all impacts that would occur, including the total destruction of portions of streams that are listed as critical habitat for Alberta’s SARA-listed westslope cutthroat trout, could be tidied up and mitigated away when the mining is finished and the landscape reclaimed.

This is what the late, great David Schindler, who passed away in early March (see p 24), recognized as far back as 1976 as “The Impact Statement Boondoggle.” Industry consultants, he wrote in the journal Science, write “large, diffuse reports containing reams of uninterpreted and incomplete descriptive data, and in some cases construct ‘predictive’ models irrespective of the quality of the data base.” These short-sighted simulacra of rigour “seldom receive the hard scrutiny that follows the publication of scientific findings in a reputable journal.” Nothing much has changed since.

In the fall of 2020, just as social media began to ignite the digital tinder of public outrage, it was time for Act II, the public hearing. This is the heart and soul of any environmental impact assessment, whereby members of the public, especially those who can demonstrate they would be “directly affected,” weigh in on the inevitably sanguine conclusions in the environmental impact statement. For the first time in Alberta history, the process was live-streamed on YouTube for all to see.

Gary Houston, Riversdale’s vice-president of external affairs, set the tone of the proceedings on October 25, two days before the actual hearing began. “We’ve filed 20,000 pages, we’ve been under the scrutiny of dozens of federal and provincial regulatory agencies,” he told the Calgary Herald. “I can’t imagine there are many questions left to be asked. Nonetheless, the process needs to be completed, and based on the work that we’ve done, we’re ready to put our best foot forward.”

For the next five weeks, Riversdale’s lawyers and experts tried to bolster the idea that the digging of a coal mine would do little harm to the stream beds and ecosystems it would strip away in the headwater tributaries of one of southern Alberta’s most important waterways, the Oldman River. On the other side of the virtual courtroom, lawyers and ranchers and scientists queried and countered Riversdale’s claims and promises, all in an attempt to point out that the mine would harm many of the things they cared about: dark skies and quietude; clean, selenium-free water; open rangelands and intact ecosystems; the need to quickly lower greenhouse gas emissions and reduce our reliance on coal to maintain some semblance of a stable climate.

They were right to be suspicious. Right next door, just over the Continental Divide from the proposed Grassy Mountain mine, the BC and federal governments have allowed Teck Resources to construct the coal mining equivalent to the oil sands: five giant open-pit or mountaintop-removal mines in the Elk Valley, despoiling the area. Predictably these gaping holes have created many of the problems Grassy Mountain’s decriers foresee. Perhaps the most relevant is the poisoning of the Elk River and its tributaries with toxic amounts of selenium which are now 75 times the limit set out in BC’s water quality guidelines, reducing westslope cutthroat trout populations by 93 per cent.

On day one of the Grassy Mountain hearing, Margaret Fairbairn, Environment and Climate Change Canada’s acting regional director, got straight to the point: The model Benga/Riversdale used to calculate the selenium limit in the effluent it wants to pour into Blairmore Creek “is based on assumptions… that decrease our confidence in the limit’s ability to ensure protection to the aquatic ecosystem” and “we have no basis upon which to validate any conclusions put forward by Benga regarding selenium….” Which is a polite way for a bureaucrat to say your predictive models aren’t near good enough for us to allow you to build a mine.

A month later, on November 24, the Grassy Mountain public hearing zeroed in on the future prospects of Alberta’s westslope cutthroat trout. Three expert witnesses for opponents of the mine—a hydrogeologist, a fisheries biologist and an aquatic ecologist—testified about the inadequacies of Riversdale’s models, the overly optimistic conclusions about their ability to mitigate their impacts, and the federal government’s legal obligations to protect Alberta’s ailing westslope cutthroat trout, whose range has declined by 80 per cent over the last century because of, among other things, the destruction of its habitat by the very atrocities Riversdale’s promoters are proposing to impose on Grassy Mountain.

Who cares about trout when an entire mountain ecosystem is at risk? Lawyers.

Unlike in the Elk River watershed in BC, Alberta’s cutthroat trout population is listed as “threatened” under the federal Species at Risk Act. And unlike other environmental laws and regulations, both provincial and federal, SARA obligates (rather than simply empowers) the government to protect

their habitat.

The trout’s federal recovery strategy has identified a host of streams and creeks along the Eastern Slopes—specifically at and around the proposed mine site—that are critical to the species’ survival. SARA, unlike the federal Fisheries Act or any provincial legislation, prohibits any person (or corporation) from “destroying the functions, features and attributes” of Gold Creek and its tributaries and the Oldman River and its tributaries (and many more waterways in the area). The punishment for doing so is a fine up to a million dollars or up to five years imprisonment.

“I think it’s reasonable to suggest that the prognosis for viable westslope cutthroat trout will certainly worsen if the footprint of mining development in the southern East Slopes is enlarged,” said John R. Post, a University of Calgary professor and co-chair of the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada’s freshwater fish specialist subcommittee. He added that the Grassy Mountain mine will destroy more critical habitat than Riversdale’s consultants estimate. “The project will involve a net harmful alteration and disruption or destruction of fish habitat, and therefore fails to ensure the distributional and population objectives for the SARA-listed species and will jeopardize the survival of the species.”

So why would Benga’s corporate executives even propose to build a mountaintop-removal mine in critical habitat for a SARA-listed species? Because they think the federal government will let them get away with it.

The public hearing for the Grassy Mountain coal mine adjourned with a click on December 2, though the public could submit further concerns until January 15, 2021. “I think we made a bit of history here in conducting such a large and complex hearing in a fully online format,” Alex Bolton said before signing off and blinking out.

It won’t be surprising if that’s the most exceptional outcome of the Grassy Mountain environmental impact assessment. Bolton’s panel has until June 18, 2021, to submit its final report to Jonathan Wilkinson, Canada’s minister of environment and climate change, who will then have 150 days to issue a decision statement from cabinet. Unless another coal mine tailings dam collapses and releases another 670 million litres of toxic wastewater into a nearby river, as happened at the Obed coal mine near Hinton in 2013—or by some miracle Jason Kenney has a revelation from God about the evils of coal—history indicates it’s pretty much a foregone conclusion that Bolton’s panel will conclude three things in its final report:

One, that regrettably and with a heavy heart, the project will likely have some significant adverse environmental impacts on a long list of things Albertans thought were protected by law, as well as on Indigenous land use, rights and culture.

Two, that the mitigation measures proposed by the owners of the mine are not proven to be effective.

And three, that in spite of all of these effects and the lack of a plausible mitigation plan, the project will provide significant economic and employment benefits, and therefore, under our authority as the AER, we consider these effects to be justified and the project to be in the public interest.

This is more or less the language used by Bolton and his AER colleagues to justify the approval of the last two oil sands mines, Shell’s Jackpine expansion (2013) and Teck’s Frontier (2019). Teck ultimately pulled the plug on its Frontier mine before the federal government decided whether to approve it, but Trudeau’s cabinet likely would have given it the thumbs up even though it would have been among the most destructive oil sands projects assessed to date.

Unsurprisingly, the Harper cabinet readily approved the Jackpine expansion, a project that required the diversion of a major river in the region and destroyed woodland caribou critical habitat, which species the federal government has so far refused to protect on provincial land with an emergency order under SARA.

Compared to Benga’s proposed mine in the Crowsnest Pass, each of these projects is enormous, and the impacts that had to be “justified in the circumstances” were far more devastating than those that would accompany the decapitation of Grassy Mountain. Such is the absurdity of the environmental assessment process in Canada, which purports to protect the environment (among other things) but rarely does any such thing.

Almost without exception, huge industrial projects that impose egregious impacts on Indigenous people, sensitive ecosystems and imperilled species, often in contravention of federal and provincial laws, policies and guidelines, are approved with an unapologetic shrug. The benefits of jobs and tax revenues always outweigh the social and environmental costs.

It gets worse. Once these projects are established, the conditions under which they were approved are often ignored or entirely rearranged in an alchemical process known as “adaptive management.” Oil sands tailings ponds, for instance, are not supposed to leak, and yet they do, seeping as much as 11 million litres of toxic waste into the underlying groundwater every day. A recent report by the Commission for Environmental Cooperation found that even when the seepage was acknowledged in environmental impact assessments and scientific studies, the federal government failed to enforce the pollution prevention provisions of its own Fisheries Act.

Plans for tailings treatment and management at Shell’s Jackpine mine and Muskeg River mine, now owned by Canadian Natural Resources Ltd., have been approved by the AER even though they don’t meet the criteria of AER’s existing approvals and fail to meet AER’s requirements and government policy. Now, the provincial and federal governments are preparing regulations to allow oil sands companies to treat and release tailings wastewater into the Athabasca River even though the conditions of their initial approvals prohibited the release of treated tailings into the river.

Coal miners too take advantage of the loosey-goosey nature of Canada’s regulatory system. When Grande Cache Coal reported that selenium levels downstream of its mine in Beaverdam Creek were high enough to pose a risk to native fish populations, AER pointed to the adaptive management provision in their environmental impact assessment and asked the company to install selenium treatment technology. Grande Cache Coal refused because, well, it was just too darn expensive.

Riversdale’s environmental impact statement refers to “adaptive management” over 500 times, a code phrase for “we’ll deal with it when we get there, even if it means reneging on the promises we made.”

It’s no wonder the creeks and rivers downstream from Alberta’s current coal mines already show signs of selenium pollution, and Indigenous people downstream of the oil sands live with the fear of elevated incidence of rare and deadly cancers. The only real surprise is that the PARH groupies and the Downstreamers are so shocked that the provincial government wants to build yet another mine in yet another important watershed—and that there are few legal ways to stop it.

Despite the doom and gloom of history, there is a glimmer of hope. Grassy Mountain and its precious streams may yet be spared. If my predictions are correct, and Bolton’s panel finds Riversdale’s pet coal project very much in the public interest despite the obvious problems it presents, the federal cabinet could decline to approve it because it would destroy or otherwise put at risk critical habitat of Alberta’s SARA-listed westslope cutthroat trout, and because the economic benefits of coal these days are just too meagre to justify the mine in the circumstances.

This welcome miracle would set a long-awaited precedent whereby the federal government chooses to give primacy to its legal obligation to protect environmental values under its jurisdiction rather than simply deferring to Alberta’s provincial prerogative for relentless industrial development no matter the cost. Such a move would give pause to other coal companies whose plans involve building mines in the critical habitat of threatened species.

Either way, the decision will likely end up in court. In the unlikely case the federal cabinet refuses to approve the mine, Riversdale and the Alberta government will no doubt take the federal government to court to have the decision reversed. On the other hand, if the feds approve the mine, and the Department of Fisheries and Oceans issues a section 73 permit under SARA authorizing Riversdale to destroy critical habitat of a SARA-listed species, environmental groups will likewise ask the courts to overturn the decision because it’s unlawful.

Who knows how a single hypothetical judge would rule in either case. What is obvious, however, is how farcical it is that the fate of a highly destructive industrial project with a multitude of significant environmental impacts hinges on whether or not it destroys a few hundred metres of critical trout habitat—and that far larger industrial projects that don’t involve SARA-listed aquatic species, like oil sands mines, get a free pass.

If Albertans truly care about clean water, healthy fish populations and species at risk—and the maintenance of a modestly stable climate that won’t wreak hell on earth for our children and grandchildren—they would do well to look beyond their parochial concern for what happens on their doorsteps and instead focus on strengthening the laws that govern industrial development and environmental protection. Without such laws, politicians and joint review panels will continue to prioritize corporate profits and environmental destruction.

Jeff Gailus moved from Alberta to Montana 15 years ago, only to find politicians and voters there to be just as short-sighted and obtuse as they are at home. So it goes.