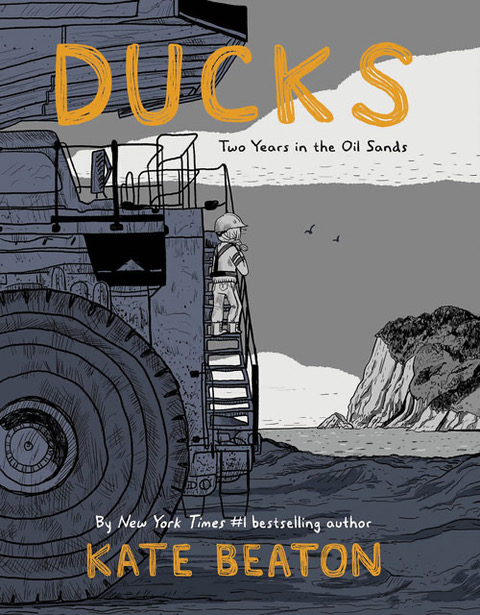

Cartoonist Kate Beaton’s graphic memoir, Ducks: Two Years in the Oil Sands, is an account of the author’s experiences working and living in northern Alberta in and around Fort McMurray between 2005 and 2008. At the outset of Ducks, Katie Beaton, our main character, leaves behind her home in Mabou, Nova Scotia, with a plan to pay off her student loans by working in the oil sands. The book’s title invites comparison between migratory birds displaced by environmental destruction and labourers, such as Katie, who move from the east coast to northern Alberta to find work. “I learn that I can have opportunity or I can have home. I cannot have both,” Katie tells the reader. Evocative, picturesque drawings of the coast of Cape Breton give way to harsh images of imposing industrial landscapes. Minor if unsettling incidents accrue toward hazardous turning points.

Through nuanced characterization, images that speak for themselves, and powerful omissions, Beaton creates a deeply moving story about labour, gender, exploitation, and acculturation into intersecting forms of violence in the oil sands. Ducks, though, is not a relentlessly heavy book. The graphic form buys Beaton some levity. And her capaciousness of outlook and skillful narrative pacing help to lift—just as ducks lift off, even in the oil sands—the hard realities that the story grapples with. She uses visual similarities between airplanes and ducks—often mallards, whose iridescent heads evoke the colorful slick of an oil spill—to link the fates of displaced birds and labourers in her story.

As Beaton writes in the book’s afterword, “The humanity of camp workers is often lost in the popular image of who goes there and why. I hope this book pokes another needed hole in that image.” Yet Beaton does manage to impart a chilling sense of the live current of risk facing those, human and otherwise, who live and work in the oil sands. Throughout the book full dark pages are covered in small white marks—which could be stars, or holes poked in darkness. The book’s narrative arc leads us toward pages where these small white marks—lights—disappear completely and the page becomes completely black, as black as tar.

I will not stop thinking anytime soon about Beaton’s representations of the oil sands—her depictions of the alarming scale of the machinery, her stories of grim, misogynistic work conditions, but also her refusal to overgeneralize, her capacity and willingness to hold space for lived complexities. Nor will I forget her drawings of the northern lights—images that capture the way the lights shift and change form against the dark.

Lisa Martin is an essayist and poet in Edmonton.

_______________________________________