Living is cheap; climate is good; education and land are free!” Published in an ad in Canada West: The Last Best West magazine in 1910, that sales pitch was part of a widespread campaign launched in the early 20th century to draw immigrants from Europe and the US to the Canadian prairies. Posters and ads in magazines and newspapers targeted specific demographics, countries, ethnicities and perceived skill sets. And those people came. Drawn by the promise of free (or very cheap) land and an advertised freedom of opportunity, the sought-after migrants kept on coming—Alberta’s population ballooned from 160,000 in 1905 to 470,000 in 1914.

More than a century later, in August 2022, then-premier Jason Kenney launched a new ad campaign, “Alberta is Calling,” that once again peddled a vision of Alberta, this time seeking to lure workers from other provinces with the promise of low taxes, cheaper housing, higher wages and a mountain view. The first phase of the campaign targeted healthcare, trades and technology workers in Vancouver and Toronto with ads that ran online, on television and radio and on billboards and posters plastered at strategic locations—“Toronto’s busiest subway station is currently a giant ad for Alberta” said a headline in a Toronto lifestyle magazine in September 2022. A second phase of the campaign launched in March 2023, with ads across eastern Canada targeting workers in occupations facing labour shortages in Alberta, promising them a $1,200 “signing bonus” if they moved west. In March 2024 a third phase targeted skilled trades workers in BC, Ontario and Quebec, dangling the carrot of a one-time $5,000 tax rebate. All told, the ad campaign cost the Alberta government at least $10-million, plus the incentive money.

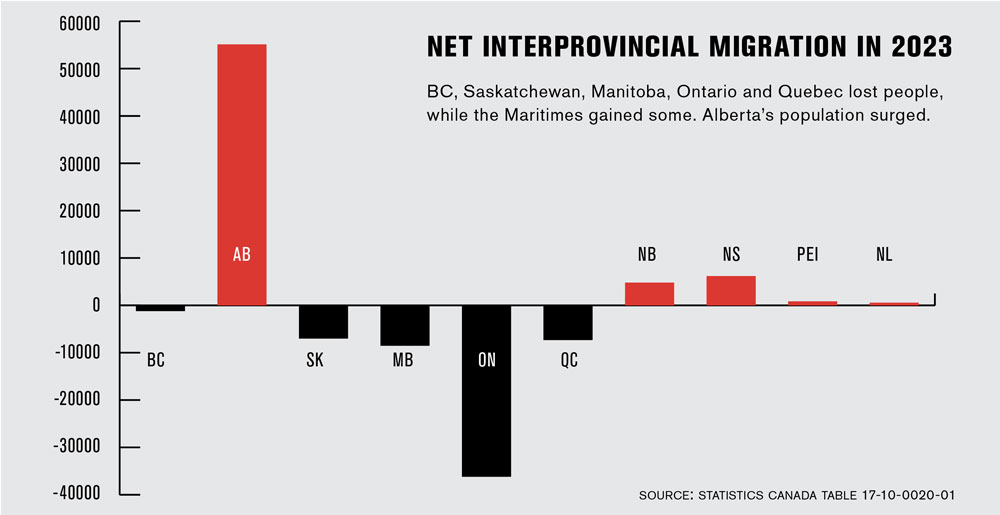

Since “Alberta is Calling” was launched, Alberta’s population has surged—by more than 204,000 between April 2023 and April 2024, a number that includes over 55,000 coming from other provinces (a Canadian record for interprovincial migration) and the rest of the influx from other countries. The province’s population boom—4.4 per cent growth in 2023 (above the national average of 3.2 per cent)—has been felt most in the cities. In 2023 Calgary’s metro-area population grew by 6 per cent, adding 96,000 people, while Edmonton’s grew by 63,000, a rise of 4.2 per cent. Alberta’s fastest-growing city, Airdrie, saw its population rise by 6.4 per cent in 2023, to 86,000, surpassing once-bigger cities such as Fort McMurray, Grande Prairie and Medicine Hat.

“The fact that so many people are coming to our province, I look at that as a positive, and we want to keep that going,” said premier Danielle Smith on the Shaun Newman Podcast in January 2024. “Let’s have an aggressive target to double our population,” from the nearly five million people of today to 10 million by 2050.

“Why?” Newman asked.

“Because then we’ll be the second-largest province,” said Smith. “We want to build this place out so that we can actually have the political clout we deserve, because right now we’re being treated as a junior partner by Ottawa.

“I think people are coming to this province because they know we do things differently here. We respect free enterprise. We respect individual liberty,” she said. “We have an obligation to be that bastion of freedom. And I think we should welcome the people who want to come here and enjoy it with us.”

The ambition recalls the famous line from the 1989 film Field of Dreams: “If you build it, [they] will come.” Except that in Alberta we’ve done the opposite—Alberta called, but didn’t first build out the field, so to speak. As a province we have not built the infrastructure or public services to absorb this many people this quickly. In the immediate aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, experts, advocates and policymakers noted the gaps and cracks that had been exposed and widening in Alberta’s public infrastructure and public services. Decades of government cuts, funding at levels insufficient to meet the pressures of inflation and population growth, deferred maintenance and a long-neglected infrastructure deficit led to cumulative impacts in which the structural pillars holding up public healthcare, public education, affordable housing, affordable utilities and public transit in Alberta were threatening to crumble. But instead of a sustained, long-term investment with a plan to fix these problems, we simply added to the load.

Alberta’s healthcare system has faced intense pressures that have resulted in widespread barriers to access for critical services. The reality for primary care is a painful one: the Alberta Medical Association (AMA) reported that in March 2023 up to 750,000 Albertans were lacking a regular primary care provider. While the Canadian Institute for Health Information puts the current figure at 15 per cent of Albertans aged 18 and over, the AMA projects that with the recent population influx the number of Albertans seeking a family doctor could soar up to 950,000.

Between 2020 and 2023 the number of family physicians accepting new patients plummeted 79 per cent province-wide, from 887 to just 190. The story is similar in every health zone: an 88 per cent decrease in the Edmonton zone, an 81 per cent decline in Calgary and a fall of 89 per cent in the South zone, where just seven physicians were accepting patients in a region with nearly 350,000 residents. The website Alberta Find a Doctor, which aims to connect those seeking care with a doctor, nurse practitioner or clinic taking patients, has posted to its search page a warning to Albertans that, due to the “limited availability of family doctors and nurse practitioners… it may not be possible to find someone accepting new patients close to your preferred location.” It directs the unsuccessful to call the AHS non-emergency line 811.

Even as hundreds of thousands of Albertans struggle to access primary care, the government celebrated a net increase in physician registrations: “More doctors registered in Alberta today than at any time in the province’s history,” boasted health minister Adriana LaGrange in October 2024. “We know Alberta is an attractive place to work as a physician.” The figures from the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Alberta show 518 additional registrations over the previous 12 months—but that increase barely accounts for the population growth in the same period. Even if all of those physicians were practising in comprehensive primary care (and evidence from CPSA, AMA and CIHI indicates they are not; overall trends show new doctors choosing specialties other than primary care), Alberta still faces what AMA past-president Paul Parks terms a “deficit position” due to “having lost 2,471 physicians” in an “exodus” from the province since 2019. In a survey of its members in September 2024, the AMA found that 58 per cent of physicians in rural, family and acute care in Alberta are considering leaving the province or medical practice altogether; 65 per cent of those physicians have acted on their discontent and begun making plans to get out by 2029.

Among nurses, a September 2024 study found approximately 48 per cent of them in Alberta are leaving the profession by age 35, putting Alberta among the bottom four provinces for losing young nurses. The ratio of nurses leaving the profession to those entering it has worsened by nearly 40 per cent since 2013. Polling by the Canadian Federation of Nursing Unions supports that figure: approximately 40 per cent of nurses across all age groups intend to leave the profession within one year, citing insufficient remuneration, overwork and understaffing, stressful work environments and a lack of work–life balance.

In Alberta the UCP government’s campaign to dismantle and restructure Alberta Health Services (AHS) and divide healthcare provision among four new agencies has left nurses feeling their concerns are being ignored. The reshuffle is imposing new workload burdens and additional costs without improving working conditions or healthcare delivery. Instead of a comprehensive and evidence-based health workforce plan for recruitment and retention, the UCP government has relied on sporadic announcements of limited funds to incentivize more people into nursing, while increasing funding for private nursing agencies to provide temporary coverage. Over seven years of available data, Alberta’s spending on for-profit nursing agencies exploded by some 13 times, from under $400,000 in 2015–16, to more than $5-million in 2021–22. As nurses in Alberta enter another contentious round of collective bargaining, political commentator David Climenhaga notes that “we now have a system in which employers plead poverty to keep staff nursing wages low while they are forced to pay far more to nursing agencies for staff they can no longer operate without.”

Meanwhile, Alberta hospitals are aging past their useful lifespan, and bed space numbers still haven’t recovered from the Ralph-Klein-era cuts in the 1990s. The long-promised and -delayed South Edmonton hospital was shelved after the UCP government halted funding for it in the 2024 budget. Despite doubling in population, Edmonton has had no new hospital since 1988. Without the South Edmonton hospital, the Edmonton zone alone will be short nearly 1,500 beds by 2026 (when the new facility would have opened). It would require the equivalent of a new hospital in each of Edmonton and Calgary to meet the healthcare needs of the more than 200,000 new Albertans that moved here last year.

Public education in Alberta is under similar strain. After consecutive years of record-setting enrolment growth, schools in the Calgary Board of Education district hit 93 per cent use of space in 2023–24, leaving little room for the projected 8,000 new students. Only two high schools in the city were anticipated to be able to accept new students in 2024–25, as total enrolment had reached 103 per cent capacity. CBE is estimated to need over 40,000 new student spaces over the next 10 years.

The challenge for Edmonton public schools is equally daunting: to meet projected enrolment growth and catch up on the existing shortfall, the district would need 50 new schools by 2033. To cope in the short term, the district implemented a growth control model in 2020 that utilizes a lottery system for oversubscribed schools.

Overcapacity leads to unwieldy class sizes and increased class complexity, along with limitations on programming as music rooms and libraries are converted into makeshift classrooms and access for students with special or additional needs is constricted. Parents of these students increasingly feel pushed out the door towards charter schools that can promise lower student–teacher ratios and more resources (though charter schools are not obligated to accept all students).

In the public system 1,500 educational assistant roles are unfilled due to a lack of provincial funding. EAs are meant to help mitigate the class size and complexity challenges. Yet, when 3,200 EAs and other support workers walked off the job in a one-day protest in October 2024, parents of special-needs students were told that for “safety” reasons their children “should stay home.” The system—in which the province directs school districts’ budgets and bargaining offers—cannot function without these EA staff, but doesn’t pay them a living wage or offer adequate working conditions.

While the 2024–25 provincial budget claimed record-high investment in K–12 education, the funding increase to public schools was only 4 per cent. The Alberta Teachers’ Association estimates that per-student funding—already the lowest in Canada—would need to increase by 13 per cent just to hit the national average.

Contrast this with the unprecedented funding in 2024 to private for-profit and charter schools for infrastructure and transportation. Charter school student spaces are now set to double—to 12,500—and, according to premier Smith, government funding will enable “thousands” of new spaces for students in “independent” private schools. That’s on top of Alberta’s uniquely high allocation of per-student funding to private schools at 70 per cent of the public rate. As the public system remains underfunded, Albertans are seeing a strategic shift of resources from the public system to the private education market.

Post-secondary institutions have been similarly starved of public money. The province has cut its share of funding to colleges and universities while capping tuition increases for domestic students. As a result, public post-secondary institutions have seen per-student funding drop to historic lows. Their response, amid limited permitted revenue streams, has been to rely heavily on increasing enrolment of international students and greatly increased fees. But now, when the number of international students is being capped across the country, students considering studying in Canada may be reconsidering that option due to limited student housing, reduced access to healthcare and fewer pathways to legitimate work. This in turn has deepened the financial crunch for public post-secondaries, leading to even more deferred maintenance, deeper cuts to support staff and a greater reliance on contracted teaching staff.

New Albertans must have somewhere to live. While housing starts appear to have made up for some of the ground lost during the COVID-19 pandemic, the roughly 40,000 units that began construction in 2024 didn’t fully cover an additional 204,000 Albertans—even if one were to generously distribute five people per home. Affordable, government-subsidized housing faces an even worse shortfall: while 1,235 new units were funded in 2024, only 250 of those were completed between December 2023 and October 2024. Meanwhile, in Edmonton alone, the number of residents without stable housing hit 5,000 in 2024, up 2,000 in a year and having nearly tripled since 2020. This affordable housing deficit has led to expensive downstream impacts—approximately $1-billion annually, including more public money going to increased policing and security, medical care and mental health and addictions support. The only long-term solution to homelessness is housing—surely that is obvious. What is less clear is who should build those houses and how. To what extent should basic necessities such as shelter be left to market forces? Should governments be obligated to ensure sufficient housing is built to meet the needs of the population they have deliberately sought to expand?

Not only housing is lacking at the local level. A 2024 report by the Rural Municipalities of Alberta calculated Alberta’s overall rural municipal infrastructure deficit at $17.25-billion. That includes deferred maintenance or replacement of roadways, bridges and water utilities that are vital to communities’ survival. Based on current provincial funding, that deficit will grow to $40.7-billion in 2028—more than doubling in three years. This state of affairs is a direct consequence of years of underfunding below inflation and population increases. In 2011–12, the provincial government budgeted $420 per capita for rural municipal infrastructure; by 2022–23 that figure had dropped to $150 per capita. Taking into account recent increases allocated in the 2024–25 provincial budget only sees a fraction of that lost ground regained—to $186 per person. A one-time grant program announced by the province in October 2024 to help small- and medium-sized communities address population pressures on infrastructure accounts for a mere 0.15 per cent of the total infrastructure shortfall.

Those wondering about the consequences of a few more years of infrastructure neglect might think back to Calgary’s dry, dirty summer of 2024, when council imposed city-wide water restrictions on residents and businesses after a crucial water main failed. As Alberta’s urban municipalities grow, so does the urgency for building public transit, emergency services, recreation facilities and services over and above keeping the lights on and the taps running. The economic reality for many municipalities, however, is challenging. The City of Edmonton, for instance, now receives less funding from the province than it did in 2009, before adjusting for inflation, even as the population of the city has grown by nearly 50 per cent.

The $10-million ad campaign worked. Alberta’s population surged by more than 204,000 between April 2023 and April 2024

Amid steady growth punctuated by spikes of immigration in recent decades, Alberta did not build the public infrastructure and services necessary to fully support that growth. This was a deliberate and explicit policy choice—enshrined again now in finance minister Nate Horner’s mandate letter from premier Smith—to hold provincial spending at less than inflation plus population growth. Collectively, as a province, we are now living with the repercussions—the day-to-day impacts of rapid growth without a sustainable plan. Instead of a plan, we have initiatives such as the “Alberta is Calling” campaign to bring in new workers.

The argument for bringing in workers has some value—of course we need construction workers to build new schools, hospitals and continuing care facilities, and teachers, nurses and support workers to staff them. Of course we need skilled tradespeople to support diversifying our economy, to develop renewable energy resources, to clean up abandoned wells—not merely to squeeze every drop of bitumen from the oil sands. But this is not, by and large, the objective of the “Alberta is Calling” campaign, nor of this government in general, which appears to favour piecemeal recruitment and retention, wage suppression and interference in collective bargaining and continued political antagonism toward public-sector workers.

For premier Smith, as she said on the Shaun Newman Podcast in January 2024, the point of quickly growing Alberta’s population is to increase the province’s political clout within Canada and to confirm Alberta as a “bastion of freedom.” But not everyone loved that pitch. In August 2024 a video clip of her appearance on the podcast was posted to X (formerly Twitter), where her call for an “aggressive target to double our population” drew scathing criticism from conservatives both online and at UCP-members-only town halls, where Smith spoke ahead of a party leadership review vote in November.

On September 12 Smith reframed her message on population growth, appearing to pivot hard with a press release that blamed “the Trudeau government’s unrestrained border policies” for infrastructure challenges in Alberta. Focusing on a federal proposal to relocate asylum seekers to Canada throughout several provinces, Smith declared “excessive levels of immigration to this province are increasing the cost of living and strain[ing] public services for everyone. We are informing the government of Canada that, until further notice, Alberta is not open to having these additional asylum seekers settled in our province. We simply cannot afford it.” [Italics mine.] In her statement, Smith emphasized that the province “has always welcomed newcomers who possess our shared values—and we will continue to do so.” As CTV News reported, “when pressed on what those ‘shared values’ are, a representative told CTV News ‘freedom, family, faith, community and free enterprise’ are important.”

The language recalled the ad campaign in the early 20th century that pitched Alberta as a homeland for self-made “pioneers” seeking freedom of opportunity. That promotion sold a version of the Canadian West that didn’t really exist, but in the selling it conjured a self-identity for the nascent Alberta. While not aligning with the reality lived by many Albertans over the last century, it created a mythology that politicians such as Smith can lean on to evoke an imagined past and the notion of an ideal Albertan. But the question is for whom and to what end?

An answer emerged on September 17, when premier Smith spoke to Albertans in a video address that began with a reference to “shared values” before announcing new funding for schools. The subsequent press release summed up the message: “The population growth has not only increased pressure in the public and separate school system but has increased demand for publicly funded charter programming and space needs.” Charter schools—a slippery slope to privatized education—would get infrastructure funding, and, in a policy unique in Canada, the UCP government will spend public money to build the bricks-and-mortar infrastructure for private schools.

In other words, the UCP government’s solution to the problem of how to bridge the gap between the growing population and Alberta’s lagging public infrastructure capacity is to privatize that infrastructure and our public services as much as possible.

In fall 2024, like clockwork, the UCP government pulled the oil price card from its trusty deck of diversions, hinting about a possible deficit in the 2025–26 budget and paving the way for lowballing public-sector wages and cutting public services. At a crucial time in our province, when massive investment in and restoration of the social safety net is needed, the spectre of cuts, flight of professionals and another round of privatization and public infrastructure firesales looms once more. While newcomers to Alberta may be unfamiliar with this playbook, for some of us this recalls an Alberta we recognize all too well.

The spiral of chaos and dysfunction is a result not of incompetence but of deliberate strategy. When the systems we rely on are broken, and the purported “solutions” on offer merely cause more damage, the most vulnerable Albertans—the very young, the elderly, the poor, the disabled or those with complex needs—will bear the costs. Is this the Alberta we want to build?

Rebecca Graff-McRae is the research manager for the Parkland Institute at the University of Alberta.

____________________________________________