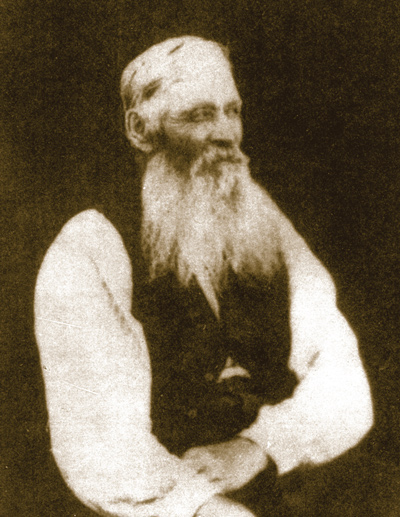

James Wishart subsisted for two days and two nights on a diet of snow and flour, then had to amputate his own gangrenous toes. (Courtesy of Vernon R. Wishart)

In 1887, James Wishart, my great-grandfather, was caught in a prairie blizzard. he had gone from his home near Rosebud to get supplies in Gleichen. On his way back, the storm forced him to take shelter under a sandstone ledge in a coulee called Chimney Rock.

Over two days and two nights, he subsisted on a diet of snow and flour. His team of horses froze to death. If he was going to survive, he would have to cover the remaining 15 kilometres home—on foot. So he set out, dragging his frostbitten body through the snow and ice. Only a short distance from home, he collapsed with exhaustion.

His wife, Eliza, caught sight of him through the window and ran to his aid with their eldest son, David. They half-dragged, half-carried James’s six-foot-six frame back to the house, where they determined the extent of the damage to his body. His toes had turned gangrenous. They would have to be amputated. Eliza placed his toes on a block, and with a knife and hammer began the operation. Overcome by the stench, she fainted. James completed the task himself.

In 1965, my sister, Shirley, attended a bridal shower where a fellow guest asked if she knew a John Martin of Rosebud. A self-educated man with an eye and ear for local history, he had written a history book that mentioned the Wisharts.

Shirley visited him and purchased his book The Rosebud Trail, which contained a description of “the great blizzard of 1887”— including what happened to James Wishart.

“Eliza’s knowledge of Indian surgery and medicine saved Jim’s life,” Martin wrote, adding that Eliza owned a medicine bag. These words revealed to Shirley a long-standing family secret: we had mixed-blood heritage. In the strokes of a hammer on flesh, sinew and bone, our ancestral roots were laid bare.

Like many western Canadians, we were unaware of our Aboriginal background because our family had concealed it. My father very likely came to believe at an early age that a native heritage was not something of which to be proud. When he was a boy, children of mixed ancestry in Western Canada heard the taunt “half-breed” and they never forgot it. My father tried to escape the stigma by moving away from the Rosebud area. he was an excellent baseball player, and in the Depression years baseball was a popular summer entertainment. The Bowden team got wind of Dad’s ability and persuaded him to come to town as a player/coach, dealing with the question of salary by hiring him to work in the local hardware store. It was in Bowden, where his native background was unknown, that he met our mother.

Dad hoped to give his children the best possible opportunity to make our way in the world. But racism always threatened to resurface. Shirley recalls wondering if our father had Indian blood, and asking him often. Every time, he said no. he died in 1959, believing he had protected his family from the shadow of racism.

In one sense, he succeeded. While growing up, my siblings and I were spared from being ashamed of who we were. We never had to face prejudice, or define ourselves by the disdain of others. By the time we discovered our native heritage, all three of us were well established in our chosen vocations. We had nothing to fear.

Prompted by Martin’s book, Shirley began to research our family history. I was busy with my duties as a United Church minister, but she kept me posted as she went. One day in 1993, shortly before my retirement, Shirley and I took a walk along the Wishart Trail in the Gaetz Sanctuary near Red Deer, a path named after James and Eliza. It was as though we were walking back in time: above the trail was the site of the log cabin where they settled in 1885 after moving from the Red River Settlement outside Winnipeg. Below the trail were the two small lakes where David, our grandfather, trapped muskrat as a young man while his sisters gathered the eggs of mud hens. It was here that I decided to build on Shirley’s research, focusing specifically on our native heritage.

With her guidance, I scoured the Hudson’s Bay Company archives and gathered information from friends and relatives, tracing our ancestry back 250 years to fur traders and their mixed-blood wives.

Two of these ancestors, William Flett and his Cree wife, Saskatchewan, lived and worked at Fort Edmonton from 1814 to 1823 before retiring and returning to the Red River Settlement. After Flett died, the 66-year-old Saskatchewan accompanied the first colonists that the Hudson’s Bay Company sent from the Red River Settlement to the Oregon Territory: 23 families totalling 121 people, 77 of them children. Saskatchewan went as the surrogate mother of her grandchildren, whose own mother had died. She was the oldest of the colonists and the only full- blooded native. The colonists travelled 2,700 kilometres, half a continent, over some of the most difficult terrain imaginable. They were under constant danger of native attack. not a single life was lost. Historian Geneva Lent says this feat “is little less than miraculous, and surely unequalled in the pioneer history of this continent.”

Remarkably, Saskatchewan made the journey back again after her son remarried. She died at the Red River Settlement at the age of 70. Though Flett and Saskatchewan had shared a life in the woodlands and on the plains, rivers and lakes of a vast northern landscape, they did not share the same gravesite. Flett was buried in the churchyard of St. John’s Cathedral, designated as the company cemetery. Saskatchewan was buried in the Indian Church cemetery.

Many Albertan families are not aware of their Aboriginal heritage. Some older people know it but conceal it. Thankfully, a door is beginning to open. In August 2005, Shirley and I attended a reunion of the descendants of the Red River Settlement. People came from across Canada and as far away as Scotland, France, Holland, Japan and Alaska to claim their roots and share their stories.

I talked to many people who, like myself, were there because they had discovered their native heritage quite by accident. Some spoke of “grandmother having a secret.” One woman, when she had tried to learn more about her background, had been told by family members, “you don’t want to go there.”

I encourage everyone to research their own ancestry, and to identify themselves as Métis, mixed-blood or First Nations members if they find evidence in their genealogy. You can begin by checking the genealogical resources at the Royal Archives of Alberta in Edmonton; the archives of the Glenbow Museum in Calgary; the Hudson’s Bay Company archives; and online search tools that provide new accessibility to historical documents and genealogical databases. The search alone promises great adventure.

By tracing our ancestry and telling our story, my sister and I can tell everyone what we never had the chance to tell our father before he died: that we are tremendously proud that our heritage is linked to the people who were inhabitants of this land for thousands of years before the white man came. We are tremendously proud of the native women in our background, without whom our white ancestors, rugged as they were, would have been unable to survive and thrive. We are proud of our great-grandparents, Eliza and James. And we our proud of our father.

After James Wishart lost his toes, the Blackfoot gave him a nickname: keesh-ket-toe Jimmie, which means “no Toes Jimmie.” When she learned the story of James and Eliza, Shirley wrote a poem, “Whetstone,” which includes these lines: “Those stumps / never did heal / he could stomp / the Red River jig / on those moccasined / toe-less feet.”

Stories like these have illuminated the legacy of our ancestors and their native and mixed-blood wives who ventured to carve out a life in a rugged and formidable continent. For my family, what began as a bolt out of the blue—a single line in a book about Eliza’s knowledge of Indian medicine and surgery—has led us to draw back the veil on our hidden past. In doing so, we have not only embraced a heritage we never knew existed, but have also reclaimed a part of our own identity. #

Vernon R. Wishart is the author of What Lies Beneath the Picture? A Journey into Cree Ancestry, published in 2006.