As a nation, in the next decade we need to build three million new homes renting for around $1,050/month, and another two million renting for less than $2,580. That, in a nutshell, is the housing challenge for Canada.

Every five years Canada’s census measures “core housing need”—the number of households whose homes are unaffordable, overcrowded or in need of major repairs. Housing is considered unaffordable when it costs more than 30 per cent of that household’s pre-tax income. In 2016 almost 1.7 million Canadian households, or one in eight, were in core housing need. But in 2021 only 1.45 million households, or about one in 10, were.

How is that possible, given everything we’ve heard about rents and home prices skyrocketing during that period? Statistics Canada is clear as to why: “The COVID-19-related government transfers lifted many households above the housing affordability thresholds, helping pay for shelter costs like rent, mortgages and utilities.” The most recent census (2021) relied on 2020 incomes. But now that the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) and other temporary income supplements have been rolled back, the number of Canadian households in core need has undoubtedly risen.

The “CERB bump”—250,000 households temporarily lifted out of housing need—gives us an immediate hint as to who we’re talking about: overwhelmingly, households whose incomes were a lot less than the $500/week that CERB provided. In fact, almost four in five households in core housing need in Canada have low or very low incomes: 1.1 million of the 1.45 million of these households have incomes under $42,000 a year, which is less than half of Canada’s median household income. Of that number, 200,000 have incomes of $18,000 or less and can afford no more than $420/month for rent.

Core housing need measures only a fraction of the people who live in unaffordable, overcrowded or uninhabitable homes. The most egregious knowledge gap is an accurate homelessness count. According to the most recent data from Statistics Canada, 235,000 people are without safe and secure accommodation at least once a year. But that figure is from 2014. More recently, biennial “point in time” counts have been interrupted by COVID. Even these exercises only count people who are found unsheltered, in emergency shelters or in “transitional housing” on one night in a little more than 60 of Canada’s more than 700 municipalities with over 5,000 people.

At least 70 per cent of 2.2 million college and university students in Canada live independently of families, the majority of them on very low incomes. Almost three quarters of these students live in unaffordable rentals—so that’s over a million more very low-income people searching for an inexpensive place to live.

A further 700,000 people live in congregate housing, including long-term care and other forms of shared housing (e.g., for people with disabilities). A high proportion of these people are occasionally homeless or live in institutions such as hospitals because of inadequate supply of supportive housing. In Ontario alone, nearly 43,000 seniors are on waiting lists for long-term care. There is no up-to-date information for Alberta—a problem in itself—but the province’s shortage of senior-care options is leaving increasing numbers stranded in hospital beds.

Tens of thousands of rooming houses have been lost in inner cities. You can’t find a room in any city in Canada for less than $500/month—more than half what most people on welfare receive. People are being turned away from overcrowded emergency shelters and ending up in growing encampments. Low-income seniors on fixed incomes are competing with service-sector workers and students who can’t find any affordable one-bedroom apartments. Increasingly these people are competing with desperate nurses, teachers and other young professionals locked out of starter homeownership.

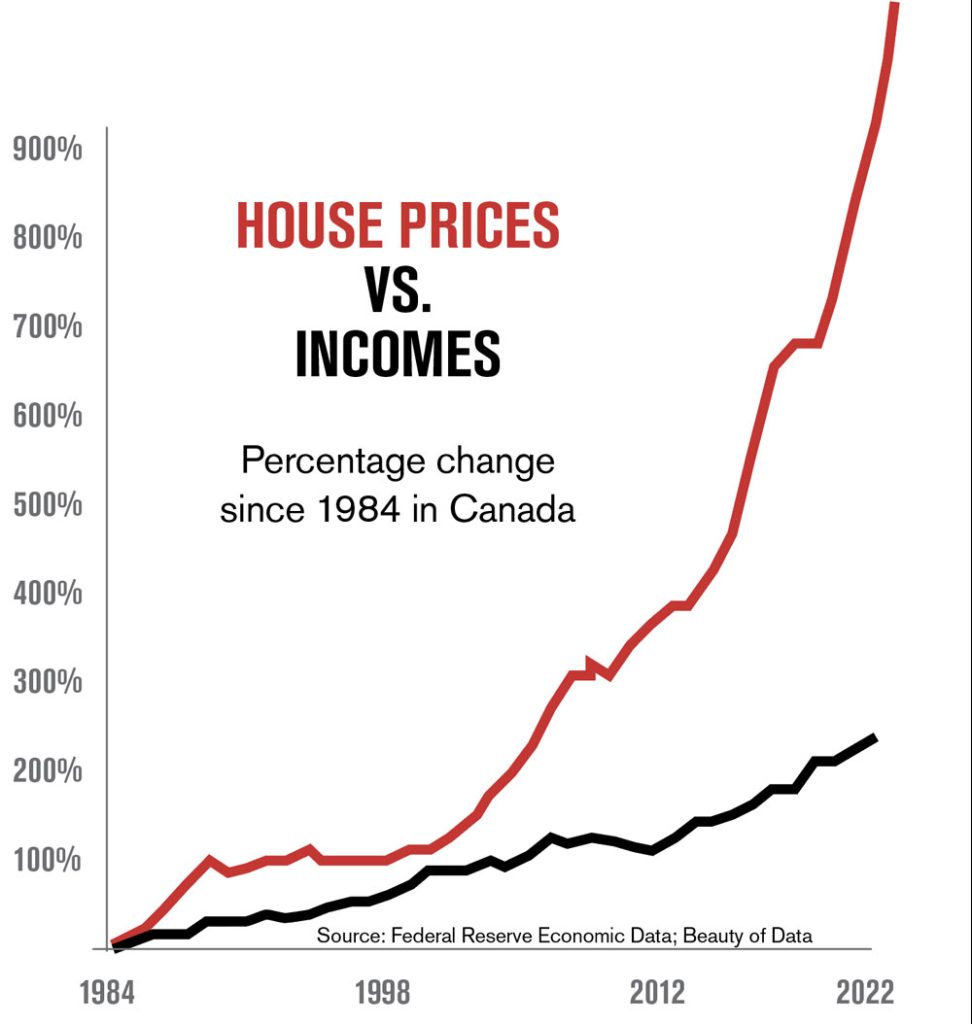

If the housing crisis is an affordability issue, with the divide between rents and incomes widening rather than narrowing, why don’t we simply provide rent supplements—or increase welfare and minimum wage, or bring in a universal basic income—to bridge the difference? First, because the difference between an affordable rent for a single person on social assistance in Alberta—$258/month—and the going rent for an average one-bedroom apartment in Calgary—$1,696—is dauntingly large. Even if welfare rates were tripled, there’s no neighbourhood in Calgary or Edmonton where that person could afford the average rent for a studio- or one-bedroom apartment. More importantly, it’s because there isn’t a sufficient supply of housing to meet the need.

In market transactions, the intersection of supply and demand determines price. However, if housing is a human need, it should not be subject to market forces. If apartments that are currently going for market rents were acquired by non-market providers (government, housing co-ops, non-profits etc.), and if short-term apartment rentals (e.g., Airbnb) were banned, that would help stem the loss of low-income rentals. But it wouldn’t necessarily create new affordable supply. And while demand-side interventions, such as providing livable incomes and renter protections, are necessary, these too would be insufficient.

In “A human-rights-based calculation of Canada’s housing supply shortages,” a 2023 report commissioned by the Office of the Federal Housing Advocate, I calculated the overall housing deficit in Canada. When one includes the existing housing deficit, the net loss of affordable housing stock, population growth and demographic change, Canada will need to build three million new homes for low- and very-low-income households by 2030, and two million more for median-income households.

Fewer homes were built in Canada in 2021 than were built in Canada in 1973.

How did we get into this mess? Put simply, a set of decisions made by governments in the early 1970s and then in the early 1990s had a huge negative impact.

In the late 1950s and 1960s, tax incentives had encouraged purpose-built rental apartments. The Canadian government eliminated these in 1972. At the same time, it introduced a capital gains tax but exempted a household’s principal residence. These changes were intended to encourage people to invest in their home and then sell it as they retired—an alternative to relying solely on pension earnings. A third element in this toxic mix of policies was municipal governments enacting stringent new zoning regulations to “protect the character” of neighbourhoods, ranging from expanding the areas zoned for single-family houses to increasing parking minimums.

Apartment construction plummeted. Condominiums, which were much more immediately lucrative for developers to sell instead of rent, became the norm in the narrow bands of land where multi-unit housing was allowed.

Mixed-income non-market housing had made up 20 per cent of new stock from the mid-1960s to the mid-1980s (between 10,000 and 30,000 new non-market homes a year). By the late 1980s the federal government had begun to move towards private-sector provision of below-market “affordable housing.” Rather than financing large-scale public housing projects erected by provincial authorities, the federal government shifted to funding smaller co-operative, municipal and community-led housing. In 1971 over half of renters between the ages of 25 and 44 could afford to buy an average-priced house. By 1981 only 7 per cent were able to do so.

The federal government had completely off-loaded responsibility for affordable housing to the provinces by 1993. Many provinces further off-loaded the costs of low-income housing to municipalities.

The consequences? Investing based on maximizing profits from existing housing—a practice sometimes called “financialization”—became much more lucrative than building new housing. Fewer homes were built in Canada in 2021 than were built in Canada in 1973. Over the past 30 years fewer than 10,000 new homes intended for low-income residents have been built in Canada.

Where are poor people supposed to go?

The federal government needs to return to policies it abandoned 30 to 50 years ago. It got back into housing policy with the 2017 National Housing Strategy (NHS) and committed, in 2019, to realizing the right to adequate housing. But its reluctance to engage in an honest needs assessment, one based on evidence of who needs what kind of housing where and at what cost, has led to it subsidizing unaffordable market rentals. Only 3 per cent of homes created under the biggest NHS scheme, the $26-billion Rental Construction Financing Initiative, were affordable to households in housing need, and all of those apartments were studios. Meanwhile, almost every economic report recommends that the federal government directly subsidize a doubling of non-market housing supply over the next decade: almost one million new or acquired public, community and co-operative homes.

Governments should provide free of low-cost land for non-market development.

This new supply would reduce the number of “suppressed households” in Canada—people who wish to live independently but are forced to share by cost pressures: for example, involuntarily doubling up with roommates; adults living with their parents. And it would take some pressure off the young middle-income households currently forced to save up to 10 years in Calgary or nine in Edmonton for a 20 per cent down payment, while being locked in to the increasingly expensive and scarce rental market.

Five million homes for low- and moderate-income households might not seem to be achievable in a decade. However, Sweden built the equivalent—one million homes for low- and moderate-income households for a country that had fewer than eight million people—from 1965 to 1974. Canada constructed a million homes via CMHC, the Canada Housing and Mortgage Corporation, for moderate-income households to buy and own between 1946 and 1960, when its population was less than a third of what it is today.

Based on what’s worked in Canada and internationally, here are some ways to get costs down and increase the supply of housing.

For starters, governments should provide free or low-cost land. According to many international reports, good land policy is the basis of any successful affordable housing strategy. Large-scale government acquisition and disposition was the basis of both the post-war Victory Homes in Canada and the successful non-market housing programs of the 1960s and 1980s. Depending on the location and size of the project, land constitutes between 8 and 23 per cent of total cost.

This land should go to non-market development. According to a 2021 Canadian study based in Vancouver, non-market developers operating from a social mission instead of for profit can produce units that rent for 40–50 per cent less. Market developers—and their finance providers—expect returns ranging from 19 per cent to 28 per cent, depending on risk tolerance. And non-market developers maintain affordability over time, compared to government subsidies to private developers. Under the NHS, private developers have affordability requirements of only 10–20 years.

Another aspect of land policy is scale, which is determined by the zoning of a site. This includes the number of storeys and units allowed, as well as design requirements such as open space, parking, setbacks etc. and mandatory financial and construction capacity of the developer. Even though constructing a multi-storey apartment building is much more complicated than a single-family home (for example, because of the need for an elevator), larger-scale development can be cheaper per square metre. Eliminating parking requirements can save up to $56,000 per unit, or up to 17 per cent of costs. Density bonuses of up to 50 per cent (e.g., a six-storey building instead of a four-storey one) could be provided to non-market or permanently affordable homes secured through a community land trust. This entity holds land and property for the purpose of long-term affordability. Small-scale affordable, accessible and energy-efficient apartments can be made possible on single or double lots through changes to building codes. While factory-built modular construction isn’t less expensive now, if its use were scaled up, it could increase speed and lower cost.

Long-term (35- to 50-year) and low-rate (e.g., 2 per cent) mortgages were the secret sauce behind the scaling-up of non-market housing in Canada. Upfront grants can help secure market financing and also help with long approval times.

To scale up low-cost housing will require massive changes to municipal processes and charges. Approval times for multi-unit housing range from three months in Charlottetown to a ridiculous 32 months in Toronto. Development charges range from $22 per square metre in St. John’s to $1,640 in Vancouver, where such charges represent 15 per cent of the cost of the home. Up to 60 studies can be required for one building…! Edmonton has been judged the best city for housing development in Canada, and it is no coincidence that Edmonton has been working hardest on simplifying zoning approvals since 2019. Development charges can be seen as an additional tax on newcomers for the “privilege” of renting or buying a home, and a further wealth transfer from renters to established homeowners. Renters already are likely paying higher property taxes. Land value taxes, and progressive property taxes, that is, levying higher rates on homes worth more than $2-million, for example, would be a far fairer way to tax infrastructure and amenity improvements—and to enable more-affordable housing.

The project I work with—the UBC-based Housing Assessment Resource Tools (HART)—aims to show the potential impact of land, finance and approval mechanisms, so that Canada can once again produce genuinely affordable and adequate homes for low- and moderate-income households. Otherwise, under the status quo, we’re condemning increasing numbers of citizens to unbearable housing stress and homelessness.

Carolyn Whitzman is the expert adviser to the Housing Assessment Resource Tools project and the author of the forthcoming Home Truths: Fixing Canada’s Housing Crisis (UBC Press, 2024).

____________________________________________