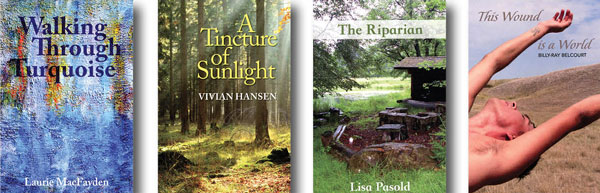

Frontenac House

each $19.95

The 2017 poetry quartet from Frontenac House is a divergent bunch, representing manifold identities and aesthetics. All four of these books are full of fictions and invented personae, as is always the case with poetry. But reading through this quartet, one also has the feeling of a correlation between the poetry and the lived experiences of the poets.

Laurie MacFayden’s Walking Through Turquoise invites the reader into an erotic discourse, mostly addressed to an unnamed lover. Love poems are a familiar genre, so we want them to surprise, and the best ones here do:

you put a ring in my heart

not the kind that encircles a finger

the kind of sound

a happy bell makes.

Many of the poems in the book are about the difficulties of finding an erotic language that can express desire: “and i need to find a better language for this.” Perhaps this is because these are poems of same-sex desire, and the work often articulates the difficulties of finding spaces where that desire is accepted. “you can’t tell,” for example, is a coming-out poem about the seeming impossibility of coming out: “you can’t tell your mother” is a refrain of lament throughout.

Lisa Pasold’s The Riparian is a long narrative poem about New Orleans. The poems incorporate the voices and actions of others, situating the speaker who has arrived in the city at the nexus of a community. These are poems of travel and discovery, consistent with Pasold’s job as a travel TV host, though these are far more risqué than the typical Discovery Channel fare—referencing sexual encounters, for instance:

We’ve come as far as we can with our sore mouths so overtly used.

His ribs have bruises shaped like fingerprints. He claims I’m a vocal version of tactile.

As narrative prose the writing is interesting—somewhat akin to a more restrained Kathy Acker—but there is little innovation in style throughout the collection. Instead there are long lines of prose, of varying lengths and of varying number on a page. Pasold employs the fragmentary form of poetry here in the service of multiple representations: of a diverse transient community; of the discombobulating effects of both travel and intoxication; of an overload of stimuli and detritus: “Peeled rubber gloves, soiled diapers, wild peas, swamp lace green glass shards.”

In A Tincture of Sunlight, Vivian Hansen documents the stories of “Old Man,” a soldier of mixed racial background (Cree and European), and the lover of the speaker in the poems. The Second World War is an important intertext in the book, with soldiers’ testimonies included as found text throughout. The poems about the war do not always go the well-trod route of celebrating courage; one poem recounts the mutilation of a dead German soldier’s body in order to steal a ring, and there are repeated references to “the clap,” of soldiers in hospital “with the only war wound they would ever get.”

Some of Hansen’s work here follows the documentary tradition of the prairie long poem, in which further found text is incorporated (such as “Uses for Duct Tape,” which includes promotional material from a northern Saskatchewan fishing lodge). These documentary materials contribute to the book’s epic scope, which ranges widely over both geography and history, moving between tales of love and of war, rendering both in realist rather than romantic terms.

If Hansen’s poems document a particular element of Indigenous history, the poems in Billy-Ray Belcourt’s This Wound is a World articulate pain and hope, personal and collective, from both an Indigenous and queer perspective. Most of the poems in the collection are lyric, though interspersed are occasional list poems made up of aphorisms and non-sequiturs: “colonialism definition: turning bodies into cages that no one has the keys for.”

Sexuality and the body feature prominently in this work, often figuring a kind of detachment from the promiscuous body, but the poems go beyond this into an exploration of the condition of embodiment itself: “if i have a body, let it be a book of sad poems.” To me, this is the most powerful collection of the quartet, and a challenging one for a non-Indigenous, non-queer reader to approach—I come to these poems with what Cornel West, cited by Belcourt in the book, calls “the normative gaze of the white man.” This Wound is a World concludes with a detailed explanatory epilogue, revealing an ambitious project—“a tribute to the potentiality of sadness” and an insistence “that loneliness in fact evinces a new world on the horizon.” Belcourt is an emerging poet to watch.

Handsomely formatted and bound, the 2017 poetry quartet presents particularly strong work, indicative of the range and ambition of poetic practices in our corner of the world.

—Jason Wiens is a senior instructor of Canadian literature in the department of English at the University of Calgary.