By the time we emerged from the Grandin LRT station on a fine May morning, a full 90 minutes before the swearing-in ceremony, we were mere flotsam on a sea of humanity. Edmonton had never seen anything like it, this amazing inundation of folks in suits and shorts and sandals and summer dresses, carrying food-laden backpacks and picnic blankets, occupying every speck of lawn, every square of concrete, and finally invading the grand ornamental pools of the Legislature grounds. Everyone seemed consumed with equal measures of disbelief and joy.

Albertans had come to be witness to history, to see the swearing-in of their first new government in 44 years. This is how a fresh chapter of democracy begins: apple blossoms wafting on the May breeze, a surge of Albertans cheering themselves hoarse, and their newly minted premier declaring, “It’s springtime in Alberta.”

The mood was somewhat different in petroleum leadership circles in Calgary. Despite Premier Rachel Notley’s immediate post-election pledge that things were going to be “A-OK” in the oil patch, currents of anger and fear swirled around an industry shaken to the core by the election result. One of the major sources of that angst was Notley’s campaign promise that her government would review the royalties paid for Alberta’s non-renewable resources. Echoing Peter Lougheed’s statements when his Progressive Conservatives came to power in 1971, Notley invited Albertans to act like owners, to steward the bounty of natural resources that are our common wealth and shared inheritance. This was a chilling prospect for oil and gas companies, who pay the royalties. Under the PC regimes of the last two decades, companies had become very used to calling their own shots. Like the engorged suitors in Odysseus’s hall, they had grown easy and familiar with having their own way.

To understand what a royalty review does, we need to appreciate the difference between royalties and taxes. Royalties are what energy companies pay to resource owners (Albertans) for the resource. Taxes are an additional charge, based on the profits companies make from all their activities, including the sale of resources. Taxes apply to all economic activity, and are recurring, whereas royalties come from the one-time sale of public assets. In essence, royalties are how Albertans capture value from the use of their resources.

Ed Stelmach was the previous Alberta premier to review royalties, in 2007, but the NDP review of 2015 was designed to go wider and deeper than Stelmach’s. Premier Notley had an eye to using the proceeds to get the province off its roller coaster of boom-and-bust economic cycles. Dave Mowat, ATB Financial’s chief executive, was appointed to lead the review. The Notley government asked him not just to determine fair royalties but to review diversification opportunities such as value-added processing, which could generate more provincial revenue from our resources. The government wanted to review the entire oil and gas industry, including its relationship to the government and the public. The idea, as stated on the government’s royalty review website, was that: “The panel is working under the principle that the people of Alberta deserve a royalty system that contributes to a vibrant, competitive industry and a strong, healthy economy where prosperity is shared.”

“The resources do not belong to the developers; they belong to the people.” —2007 Royalty Review

Mowat was an astute choice to lead the panel. As a banker he had the confidence of business and industry. But he also comes from a tradition of public banking. Prior to being appointed to lead ATB—one of the few government-owned banks in North America—he led the largest credit union in Vancouver. ATB’s role is to serve the Alberta community as well as to bring profit to the provincial treasury.

Mowat spent the summer of 2015 assembling his panel, and his choices rendered the review immune from doomsayer predictions that the NDP would pillage the oil patch. Annette Trimbee, vice-chancellor of the University of Winnipeg, was formerly a deputy finance minster in Alberta; economist Peter Tertzakian is respected in industry circles for his rigorous data and solid forecasting models; Leona Hanson, mayor of Beaverlodge, brought direct experience as a resource-town politician. She also has an MBA.

Ultimately the mandate given to the panel included six undertakings: to assess the royalty framework for the three different sectors of the oil and gas industry (conventional oil, natural gas and oil sands); to assess how the government generates revenue from oil and gas land sales; to understand and assess how a royalty regime can generate diversification opportunities (including more refining and upgrading in Alberta); to compare this province’s royalty framework with those of other jurisdictions; to project short- and long-term trends that would affect Alberta’s resources and the revenue from them; and to develop criteria for continuously assessing the effectiveness of the royalty framework. It was a tall order.

As Mowat’s panel launched its work, it posted every submission it received to the “Let’s Talk Royalties” website. Albertans were encouraged to use the website to express their views. The panel added to the available review information by informing Albertans of weekly progress. As the process went on, the review’s mandate seemed to crystallize around its third undertaking: the generation of diversification opportunities. That focus was underscored by a brief given to the panel by AIHA, Alberta’s Industrial Heartland Association, an organization of value-added processors. The association’s brief called for fiscal levers such as tax incentives to encourage more processing, upgrading and refining in Alberta.

The 2015 royalty review happened during a period of relentless focus on climate change. While the panel gathered information, deliberated and wrote its report, the world’s major oil companies were declaring themselves committed to dealing with this global problem. When Royal Dutch Shell CEO Ben van Beurden came to Alberta in November 2015 to attend the start-up of the province’s first major carbon-capture project, Fort Saskatchewan’s Shell Quest venture (supported by the province and the federal government), he emphasized the need for a robust carbon tax as an incentive to spur the transition to a greener and more sustainable economy. At a time when the Notley government was under fire from opposition leader Brian Jean for doubling the province’s levy on heavy carbon emitters to $30 a tonne—a job killer, according to Jean—van Beurden said that a carbon tax of $60 to $80 a tonne would fit with his firm’s calculations of what makes economic sense.

Notley has much more room to manoeuvre than the Stelmach government had in 2007.

The recognition that the evolution away from fossil fuels to other forms of energy is within the ambit of today’s large hydrocarbon companies amounts to a stroke of luck for Premier Notley and Economic Development Minister Deron Bilous as they consider how to implement the royalty review findings in the months and years ahead. The appetite for transformation gives the Notley government much greater room to manoeuvre than was available to the Stelmach government after its 2007 royalty review.

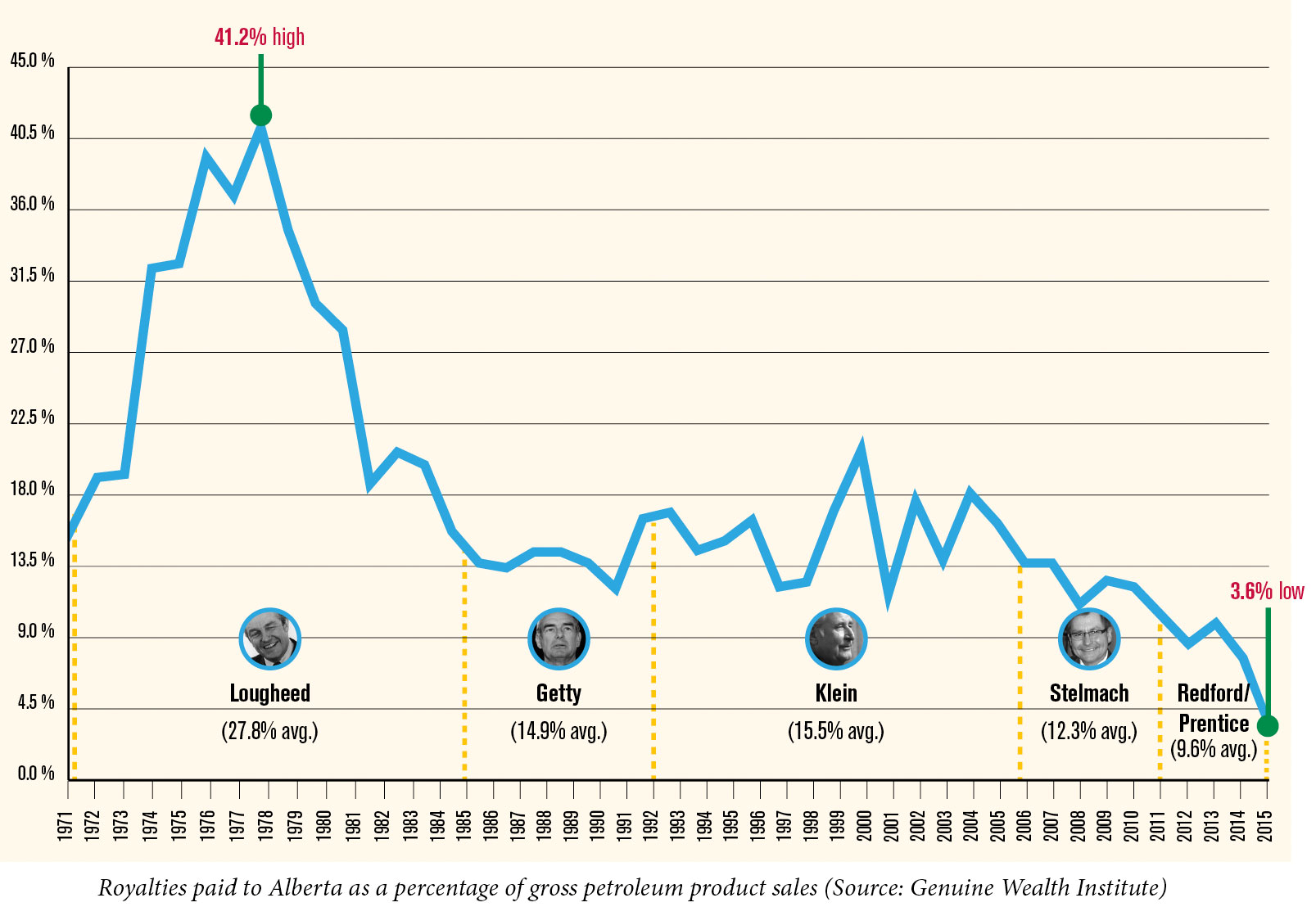

Stelmach had imagined he would be able to revive Premier Peter Lougheed’s 25 per cent royalty formula. Lougheed’s government demanded and received fair value for Albertans’ oil and gas. From 1971 to 1985, resource royalties averaged almost 28 per cent of gross oil and gas sales in the province. In our best year, 1978, Albertans collected royalties representing 41 per cent of gross sales.

From 1971 to 1975, when industry was focused on conventional oil, Lougheed managed to involve the governments of Canada and Alberta as well as the private sector in kick-starting oil sands development. Recognizing also that processing and refining within Alberta had not reached its potential, Lougheed wanted to establish a petrochemical industry here. “Why would you want a petrochemical industry when we have such a big one in Sarnia, Ontario?” Canadians asked. But Lougheed persevered.

His approach was a radical shift. The old mindset of Albertans, and Canadians generally, was that we were a producer of raw materials and our job was to gather resources and ship them away, far away, for processing.

Lougheed changed that.

With this new-found consciousness, Alberta tested the limits of government involvement and ownership in the economy. In 1973 Premier Lougheed set up a privately organized but publicly owned and run oil company, Alberta Energy Company. AEC was given prime leases and grants and a mandate to develop resources for the benefit of all Albertans. Through this investment, the Alberta government also had an equity position in oil sands. AEC’s shares were offered to and widely held by ordinary Albertans. AEC’s first share offering in 1975 attracted 60,000 buyers, and those shares eventually split 3-for-1 in 1980.

Lougheed’s successors lacked the iron will and political vigour to keep on ensuring that Albertans acted like owners. AEC, as a symbol of that retreat, went from 50 per cent public ownership in 1975 to being entirely privatized during the Klein era by 1993. The famous Lougheed objective of a 35 per cent share of oil and gas profits also began to erode. Under Ralph Klein the percentage that went to Albertans fell below 20 per cent, then below 19 per cent, then 17 per cent. Finally, the Klein government stopped measuring. Under pressure, Klein countered that he believed Albertans were getting their rightful share. To prove his point, he sent one of his cabinet minsters around to ask the oil companies if they were paying enough in royalties. They said they were. There you go.

When Ed Stelmach succeeded Klein as premier in 2006, he knew the oil industry had far too much control over Alberta’s publicly owned resources. He knew Albertans should demand a fairer share, and he wanted to use revenue from non-renewable resources to build a stronger foundation for the future. Indeed, Stelmach wanted to revive the neglected Lougheed principle of not just collecting more royalties but leveraging that wealth into a more diverse and sustainable economic future. Lougheed had said that shipping unprocessed oil out of Alberta was like farmers selling their topsoil. In justification of his royalty review, Stelmach made the same comparison. The Stelmach royalty review had two purposes: to determine whether Alberta was indeed getting its fair share as owner of the resource, and to use the review to launch and establish a new energy strategy that would add value, while developing the oil sands responsibly.

The Stelmach review panel was chaired by forestry executive William M. (Bill) Hunter. The panel’s 2007 report, “Our Fair Share,” stated that Albertans were not receiving their fair share from energy development and concluded that royalty rates and formulas had not kept pace with changes in the resource base and in world energy markets. The report recommended the Alberta government rebalance its royalty and tax systems so that a fair share would be collected. It recommended increased rates but only a modestly higher take for oil sands. It actually proposed reduced royalty rates for conventional oil and gas when prices of those commodities were low.

The royalty review is a chance for an Albertan economic and societal transformation.

The 2008 financial market collapse was the undoing of “Our Fair Share.” A weak economy drove down the world oil price and enabled the oil and gas sector in Alberta to push back hard against the new royalties. This prompted the Stelmach government into a series of ill-conceived retreats. Changes enacted by the government in the spring of 2009 resulted in Alberta taking in less revenue than it would have if the old royalty regime had stayed in place.

But what survived of the 2007 restructuring of Alberta’s royalties was perhaps the most important element: the price-sensitive royalty structure introduced on oil sands and heavy oil. The increase in revenues from heavy oil and oil sands was considerable, and the corporations that paid these royalties—the small proportion of producers that are responsible for most of Alberta’s energy production—stayed quiet because they knew they were still getting a great bargain in global terms. Alberta royalties remained bottom of the heap while governments around the world—from Norway and Kazakhstan to Alaska and Venezuela—demand and receive a much greater proportion of net revenue from the exploitation of their resource wealth.

That Alberta’s take of oil revenue was still low by world standards was not entirely the fault of the Stelmach government and its royalty review. Stelmach and his colleagues came to politics through community service, mostly in small-town and rural Alberta. They were rooted in the fading culture of looking after your neighbours and measuring a person’s worth by what they give back to the community. These values left Stelmach ill-equipped to deal with a winners-and-losers culture of big money and rampant egos. This was the same big-money culture that had resented Lougheed for raising royalties in the 1970s. Ernest Manning hadn’t known how to deal with the new oil culture in Calgary either.

Just in case the Stelmach government were planning another attempt to reassert the ownership rights of Albertans, the Calgary oil patch reduced its financial support of the PCs and created and funded the corporation-friendly Wildrose Party. This is the same Wildrose Party that howled at the door throughout Notley’s royalty review, demanding that the owners of Alberta’s resources continue to give those resources away and allow companies to maximize their profits. Indeed, Wildrose leader Brian Jean told Fort McMurray Today that he was “embarrassed” by Notley for launching the royalty review and a climate change panel in the early days of the new government. Jean didn’t mention that Alberta’s royalty share for 2015–2016 is forecast to be the lowest in our province’s history—just 3.6 per cent of the expected gross value of oil and gas sales, a mere sliver of Lougheed’s 35 per cent goal.

It’s noticeable that Wildrose is getting little rhetorical support from large, multi-platform energy firms. The big foreign investors in the oil sands—Royal Dutch Shell, Husky, Total, Statoil, Abu Dhabi’s TAQA—have all stayed on the sidelines while some of the local guys rant and rave.

During the Stelmach and the Notley royalty reviews, Albertans have faced a significant question: What is the moral justification for the production and consumption of fossil fuels? In effect, the moral justification for developing the oil sands as sustainably as possible is that we can use the wealth generated by them to fund the transition to a more sustainable future.

Already it has become clear that big fossil fuel companies have the capital, the resources and the will to pursue energy alternatives. Alberta can use the Mowat report findings on royalties to put in place both the regulatory framework and the public resources needed for greener oil sands production and the development of new energy sources for the future. The review’s successful implementation at the beginning of 2017 may depend on how vigorously Notley decides to leverage the owners’ share into a different energy future for Alberta.

In the context of other new government initiatives—the economic diversification panel led by University of Alberta business school dean Joseph Doucet, and the climate change review led by Doucet’s colleague Andrew Leach—one can see the royalty review not only as a chance to reclaim citizens’ fair share but as the foundation of an Albertan economic and societal transformation. In this regard, Rachel Notley could be seen as the “natural heir” to Peter Lougheed’s legacy.

Satya Das grew up in India and Canada and completed a fellowship at Cambridge University. He lives in Edmonton.