Shortly after the death of Edmonton writer Gloria Sawai, I was invited by her children, Naomi and Kenji, to go through her library and select whatever books I should like to keep. Obviously this was a considerable honour, and I was given it because I had been close to Gloria for almost 20 years. Though I knew Gloria well, especially her literary self, I was nonetheless surprised by certain volumes in her personal library. Most intriguing of all were several inscribed copies of the books of US novelist Nelson Algren, whose 1949 novel The Man with the Golden Arm won the first-ever National Book Award and was later made into a popular movie starring Frank Sinatra and Kim Novak. These signed Algren books on Gloria’s shelves hint at the apprenticeship of the writer I did not know. Sawai, who was born in Minnesota and had gone back to her native state to study English, likely met the successful novelist at a public reading, but the inscription is enticingly personal: To the barefoot girl with the yellow, yellow hair and the blue, blue eyes.

The man with the golden arm, the girl with the yellow hair. Literature is filled with such almost invisible but tantalizing encounters. What really intrigues me, however, when I consider the whole of Gloria’s life, is how, early and late, people always remarked on the brilliance of her blue eyes, relating that piercing colour to an intensity, clarity and honesty of character that shone not only in her personality but perhaps even more evocatively in her one published book, the widely praised A Song for Nettie Johnson.

Born Gloria Ruth Ostrem in Minneapolis on December 20, 1929, she was not yet a year old when her father accepted a position as Lutheran minister in the small town of Admiral, Saskatchewan. Eight years later the family moved to another parish in Preeceville. In 1945, when Gloria was 13, they moved to Ryley, Alberta, and Gloria completed high school at Camrose Lutheran College (now Augustana College). It was the western landscape, then, that informed Sawai’s artistic sensibilities the most. Wind. Sky. Prairie. Rock. Small towns with their eccentric and quirky inhabitants. Some of her best work would be located in the fictitious town of Stone Creek, Saskatchewan, and it’s there that we meet the teachers, ministers, alcoholics, communists, atheists, Jews, Pentecostals, Mennonites and Catholics that people her stories. And it’s there too that we meet the poignant children, often bored by small-town life, sometimes mean-spirited but almost always wide-eyed and questioning.

Gloria Sawai. December 20, 1932-July 20, 2011

As the US author Flannery O’Connor wrote, “Anybody who has survived his childhood has enough information about life to last him the rest of his days.” Sawai’s finely crafted stories, with their minute attention to detail, draw heavily on children’s wondrous and naive reflections. Her scenes are still lifes of epic proportion, infused with beauty, awe, humour and grace. Who can forget the young atheist Ivan Lippoway, who plays crack the whip at the skating rink and skates so fast that Elizabeth Lund, the Lutheran minister’s daughter, spins out of control at the end of the line and slams into the side fence, knocking the wind out of her? Or the woman drinking wine on a porch in Moose Jaw who has the extraordinary experience of having Jesus stop by for a visit on her sundeck? Or the angel with sturdy wings who hovers, ever so briefly, over Nettie Johnson before flying away to the US “because some things are too hard for angels to endure, too human and incomprehensible.”

The magical moments, the light and humorous touches, are too numerous to catalogue, yet Sawai never shies away from the fundamental darkness and complexities of human existence. Think Norway. Think winter. Think bare rock. While her characters often have glaring flaws, they nonetheless, at some critical moment, experience the redemptive power of grace.

This is perhaps not surprising. As the daughter of a Lutheran minister, Sawai grew up in a household in which the biblical “word” was profoundly important. Is it any wonder that she attached that same importance to language in general? From the time she was a child, she enjoyed reading and making up stories. Not all of the books she read, however, were acceptable to her parents. Once, her mother sent back all of Sawai’s Book of the Month Club selections because she found them too racy. When Gloria began high school, she was given a book called Especially Babe, written by the Alberta novelist Ross Annett. The book made a large impression on her, and, as the story “A Canadian Novel” (see p 42) makes clear, helped define Sawai as a writer.

Yet a life in letters was not acceptable for a woman coming of age in the 1950s. Teaching, however, was. In 1953 Sawai received a B.A. in English from Augsburg College in Minneapolis, and afterward taught literature and drama to high school students for a number of years before moving back to Camrose.

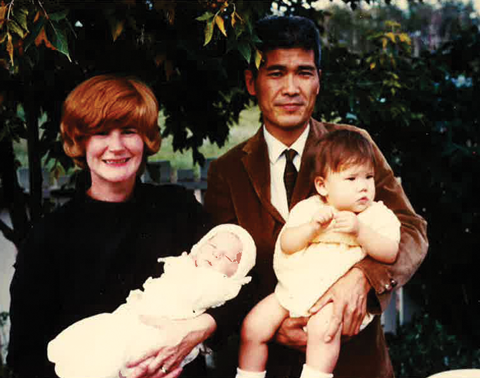

In 1962 Gloria married the Japanese-Canadian printmaker Noboru Sawai. Shortly after, they moved to Minneapolis and started a family while he completed an M.F.A. In 1969 they moved to Japan for a year while Noboru studied printmaking, and in 1971 they returned to Canada when he accepted a job at the University of Calgary.

The western landscape informed her artistic sensibilities the most. Wind. Sky. Prairie. Rock. Small towns.

It was in Calgary, when the children were small, that Gloria became depressed. She told me that one day, Noboru came home to find her staring at the wall. Concerned, he asked what she needed. When she said she needed to write, he responded that if she didn’t pay attention to that artistic hunger she would become sick. He then suggested something amazing: why didn’t she do a degree in creative writing? The idea of going to school for an M.F.A. excited her, so Gloria applied to the University of Montana. Some time later, however, a rejection letter arrived. Once again Noboru was a great support. “Do you want to do this?” he asked. She nodded. “Then let’s go.” They drove down to Montana and met with the head of the writing department, who agreed to let her into the program. The rest, as they say, is history.

In the late summer of 1973, Sawai packed up her children and a few belongings and drove south of the border to pursue her writing career. It was in Missoula that she wrote the internationally anthologized story that would put her on the literary map. In fact, her writing career was defined by two critical developments: the wide anthologization of “The Day I Sat with Jesus on the Sundeck and a Wind Came Up and Blew My Kimono Open and He Saw My Breasts,” and the winning of the 2002 Governor General’s Award for fiction for her one published book. The time span between the writing of her “Jesus story” and the appearance of A Song for Nettie Johnson was 30 years.

In 1996 Gloria had been struggling to finish the novella that would become the title story of her collection. That year, she was also working at Grant MacEwan College, but teaching was taking up too much of her time. Fate intervened in the form of a major heart attack. After recovering, Gloria never returned to the classroom. “When I was in the hospital,” she told me, “I prayed that I would live long enough to finish my novella.”

Fortunately, her prayer was answered.

A Song for Nettie Johnson contains a novella and eight short stories. In the title piece, we are introduced to the town of Stone Creek,

“a huddle of ragged buildings beside thin and dusty roads.”

It’s October, and Eli Nelson, one of the town drunks, is about to begin his annual ritual of sobering up in order to conduct the town choir in a Christmas concert of Handel’s Messiah. But this year Eli has moved in with “crazy Nettie,” an outcast who lives in a trailer on the lip of the quarry. Damaged in spirit and mind, Nettie Johnson carries the heavy burden of her sad history.

Eli carries his own sadness. He was once a promising musician, but his university studies were forever interrupted when a van arrived on campus and a nurse X-rayed everyone’s chest. Eli, it turned out, had tuberculosis. The 19-year-old was put on a train and sent to Fort Qu’Appelle to the sanatorium. Eventually, as his dream of becoming a musician died, he turned to alcohol.

But his enthusiasm for Handel’s music spreads like wildfire through the small town. “Imagine,” someone says, “the Messiah in Stone Creek!” Two more of the town alcoholics also sober up for the annual concert: old Doc Long and Sigurd Anderson. Musicians arrive from Moose Jaw. And as the day of the concert arrives, everyone gathers in St. John’s Lutheran Church. From the farms south of town, they come. From Shaunavon, Moose Jaw and Swift Current they come.

Inside the church, Reverend Long looks out at the crowd in amazement.

He knew, of course, that McFarlane would come and Ross and others not of his own denomination, including Mrs. Long, the doctor’s wife, who’s United. But he wasn’t prepared to see Mrs. Donnelly, a Catholic, and five Mennonites from north of town. He feels a small ripple of excitement up his back and on his arms. How extraordinary. Even Mrs. Donnelly. And the Mennonites.

Eli, sober since mid-October, stands before the choir in his borrowed tuxedo, his brown, scuffed shoes polished to a dull shine. His baton rises. The congregation holds its breath. Then the glorious sounds of Handel’s Messiah flood the church and unite the many denominations in celebration.

There are many such memorable moments in A Song for Nettie Johnson. In perhaps her most powerful story, “Mother’s Day,” Sawai tells the story of 13-year-old Norma Hagen, who can’t stop thinking about an incident that took place when she was 11. Her gaze is a piercing one, and when Norma turns it on her parents, the effects are both comical and insightful. Of her mother, who is engrossed by storms, she says, “On very snowy days or rainy days my mother abandons all her housewifely responsibilities and sits in front of her window all day, just looking out… In some respects my mother is a bit lazy. Nevertheless, I find her an interesting person.” We learn that her father plays chess by correspondence. A recipe box contains postcards from all over the world of each player’s individual moves. “Sometimes it takes nearly a month for a card to reach another country,” Norma notes, “so you can imagine how long one game might last.”

Such revealing yet simple details about Sawai’s characters enhance the poignancy of each story. Eleven-year-old Norma, who is both secretly thrilled and self-conscious about the “development” of her breasts, lies sick in bed and is shocked to discover her father standing in her doorway with a mustard plaster for her chest. Her sense of betrayal is profound. How could her mother allow this to happen?

I felt my eyes sting and I knew I was going to cry. I felt the wetness press against my eyeballs and drip over the edges of my eyes down the side of my head, into my hair. I couldn’t say anything. I just lay there and cried.… He looked down on my chest. I looked up at his face and saw his eyes open a little wider, and I knew he saw my development. It was pretty clear to me that he saw.

Two days later a cruel event takes place in which Norma plays the lead role, with the personal shame she’d recently experienced forming the backdrop. What follows is Sawai’s delicate exploration of human nature. “And how do you go on from there?” young Norma asks. “What do you do next if you’re a person of faith?”

I know what the Buddhists would do. I’ve read about Buddhists in the encyclopedia. They think that if you know you’ll do wrong by going places and doing things, then just don’t go there. Stay where you are. Sit. Then you won’t sin.

But I’m not a Buddhist. I think it’s more like this. You go to places, knowing all along it won’t be just right or true. There’ll be darkness there, and some damage. But you go just the same. There’ll always be some light. Pieces of it anyway. And you can notice that.

The subtle humour, the short sentences containing profound truths about the human condition. This is trademark Gloria Sawai. For we all go places, and damage is done. But Sawai would have us believe that with our imperfections comes the possibility of redemption.

While the “Jesus story” was her most famous work, Gloria often rolled her eyes when people commented on how much they liked it. What irked her most was that she’d written it in one sitting and the words had flowed effortlessly. She never again experienced that gift of ease in her writing, so it seemed unjust that the “easiest” story was also the one most people knew her by.

Her own favourite was the last story she wrote for the book, “Oh Wild Flock, Oh Crimson Sky,” in which the young Elizabeth Lund debates Ivan “The Brain” Lippoway on the existence of God. Once again we have a child narrator with mature insights. How to prove God’s existence to an atheist? Not with the Bible, surely. After much deliberation, Elizabeth decides to use poetry to identify the abundance of beauty in our lives. Ivan’s debate, by contrast, is a scientific one: he uses gravity and mathematical equations to appeal to his classmates’ reason. In the end, however, Elizabeth’s appeal to their emotions wins the day. The story ends where it began, at the ice rink. Only this time, instead of crack the whip, Ivan skates over to Elizabeth, whose heart races at the sight of him. He swirls her around the ice, moving quickly past the other skaters. Elizabeth exults in this moment of rapture. “I looked up at the black sky and the stars,” she notes. “The air was cold on my face. And, oh, the beauty! I could hardly breathe.”

In 2001 A Song for Nettie Johnson was published by Coteau Books. “I remember editing every line of the book,” Edna Alford says. “The stories were pure magic. Every semicolon was perfect. The stories were independent, autonomous, living organisms. The work was so fine, and Gloria knew that.”

Other writers knew it too. Many of the signed books in Sawai’s library contain inscriptions of eager anticipation. Tillie Olsen, Alistair MacLeod, Adele Wiseman, Margaret Atwood, Joy Kogawa, Elizabeth Smart, Edna Alford, Don Coles, Don McKay, Fred Stenson, Curtis Gillespie, Merna Summers, Joan Clark, Jacqueline Dumas. The list is lengthy, the respect for Sawai’s work and personal qualities faithful. This respect is also clear in the comments various writers have made about her since her death. Alistair MacLeod tells me, “Gloria was a wonderful writer who had rare insights into the human character. She was a very, very fine writer who produced exceptional literature.” For Sandra Birdsell, “Gloria was like the writer Grace Paley… in the sense that she had such a distinct voice and wrote about the people around her with the forbearance and humour of a benevolent god.”

A family photo, circa 1968 (with husband Noboru, daughter Naomi and son Kenji.)

And Fred Stenson relates a telling story about the effect Gloria’s public readings often had on her audiences: “Back in 1984, Gloria, Beverly Harris and I were together in a NeWest Press anthology called Three Times Five. I had not met Gloria before. After I read I was thinking vainglorious things such as that it was the best reading I’d ever given. I was quite puffed up. Then Gloria read. I was floored. Bar none, it was the best reading I’d ever heard, and my fat head shrank to subnormal size in an instant.”

Gloria’s dramatic stage presence made her readings more than memorable. She knew when to pause for effect. When to punctuate the air with her hands. When to raise her voice, and when to drop it to a whisper. She knew, in other words, how to remind us, often in a humorous manner, of our flawed humanity.

Sawai’s endless curiosity about people and places was reflected in the eclectic tastes revealed by her library. In addition to works by literary luminaries, she also had an extensive collection of Canadian plays (which fuelled her own play writing endeavours), instructional books about writing, a large number of religious books, poetry collections and books on Norway and Japan. Also on the shelf was The Messiah Book: The Life and Times of G. F. Handel’s Greatest Hit, a history of the one of the world’s most celebrated artistic creations.

On Tuesday, July 19, 2011, Gloria Sawai felt a familiar pain in her chest. She phoned her sister-in-law and said, “I think I’m having another heart attack.” Then she called an ambulance. She died before reaching the hospital.

After Handel’s first performance of Messiah in London in 1743, he told a friend, “I should be sorry if I only entertained them. I wished to make them better.” The same could be said of Sawai’s ambition for A Song for Nettie Johnson.

Theresa Shea was Gloria Sawai’s friend for almost 20 years. She was honoured to give the eulogy at Gloria’s funeral.