Slipping my pack onto my back, I walked along the gravel trail. As it is most summer days, the narrow mountain path was busy with tourists clutching smartphones on selfie sticks and lugging the occasional full-frame camera and hefty tripod. Unbeknownst to most of them, they were following a decades-old ritual, visiting the viewpoint overlooking one of the most photographed places in the Canadian Rockies: the radiantly turquoise Peyto Lake.

Before reaching the lookout I turned onto a smaller dirt trail, and in a few steps I’d left the bustle behind me. Hiking steadily downhill through a forest of brawny old-growth spruce and fir trees, I emerged onto the breezy expanse of gravel beds braided with aqua ribbons of glacial melt, all rushing to fill the lake.

My destination lay four kilometres and 500 metres higher up the rubbly valley—the glacier whose meltwater fills that lake. There, I would rendezvous with several scientists at the Peyto Glacier research site, a cluster of small, weather-worn buildings perched on a rock-cluttered knoll. Built in the 1960s, the site is a living legacy of a worldwide glacier inventory project in which Canada played a key role, and where research continues.

To reach the site I skipped and splashed through shallow rivulets until I reached a larger channel pulsing toward the lake, considerably wider and deeper. Switching my hiking boots for lightweight sandals, I stepped into the icy flow. With a hiking pole to steady me gripped tightly in each hand, the water surged at my knees as my feet sought out the flattest stones that didn’t wobble. I was immersed in the rushing headwaters of the Mistaya River, which feeds the North Saskatchewan River, water that flows through Edmonton to central Saskatchewan and ultimately to Hudson Bay, where polar bears hunt for seals on its winter-frozen surface, and walrus, dolphins and orca swim and feed.

Just as I feared being flushed into the lake and beyond, I reached the north bank. Boots back on and invigorated head to toe, I located the start of the foot-hewn trail. Two thankfully smaller creek crossings later, I ascended the steep hogsback moraine ridge. Finally the glaciology buildings emerged into view, with the glacier tongue beyond. While some of the scientists and bulky equipment reach the site by helicopter, for those who hike the same route as me, it’s just another walk to work.

Caroline Aubry-Wake is one of those researchers. A Ph.D. student with the University of Saskatchewan’s Canmore-based Coldwater Laboratory, she works under John Pomeroy, Canada Research Chair in Water Resources and Climate Change at the university. Her work contributes to his team’s studies to understand how retreating glaciers, changing landscapes and a warming climate are affecting water resources in mountain basins in the Canadian Rockies. Her first visit to Peyto Glacier, though, was in winter, when she and friends skied the popular Wapta Traverse. Carrying avalanche and glacier safety gear plus sleeping bags and food, they skied 40 kilometres across sparkling icefields and glaciers where the only tracks are made by skiers, wind or wayward wolverines, spending nights amidst the icefields in Alpine Club huts.

“I really enjoy spending time on the Wapta,” Aubry-Wake said. “Whenever I go for fun, it also helps me with my science, to see how the landscape evolves in the winter. I can take that understanding into my work.”

In autumn 2017 she launched her Ph.D. project at Peyto. She’d previously spent two summers studying glaciers in Peru’s Cordillera Blanca while earning her masters in earth and planetary sciences at McGill University. For her doctorate she’s working alongside Pomeroy and fellow Ph.D. candidate André Bertoncini to study how wildfire smoke influences glacier melt, by comparing years with a lot of fire activity in Alberta and BC—including 2017 and 2018—with the years that followed, such as 2019, when fires were fewer but a soot layer from previous years darkened the glacier surfaces and increased the melt rate.

Glaciers will shrink 60–80 per cent by the end of this century. The biggest loss is predicted to occur between 2020 and 2040.

Her work with the Coldwater Lab includes computer modelling, collaborating with other scientists to examine conditions at Peyto Glacier from the early 2000s through to 2090 in an effort to understand how the North Saskatchewan River basin will function when Peyto and most of the Rockies glaciers have completely melted. Previous studies by the Western Canadian Cryospheric Network have demonstrated that some 300 glaciers in the mountain national parks of the Rockies were lost between 1920 and 2005. And a UBC study led by professor emeritus Garry Clarke and published in the journal Nature Geoscience in 2015 determined that, based on conditions and trends relative to 2005, the volume of glacier ice in western Canada will be reduced by 60 to 80 per cent by the end of this century. Few glaciers will remain in the interior and Rockies regions, the study concluded, while glaciers nearer the Pacific Ocean, particularly those in northwestern BC, would survive “in a diminished state.” The biggest loss, they predicted, would occur between 2020 and 2040, with potential implications of those reduced/depleted glaciers including “impacts on aquatic ecosystems, agriculture, forestry, alpine tourism and water quality.”

After the summer of 2021’s record-smashing high temperatures across western Canada, however, and the dry weeks with smoke thick as dryer lint from BC wildfires that followed, many doubt Peyto, and other Rockies glaciers with similar characteristics, will last half that long.

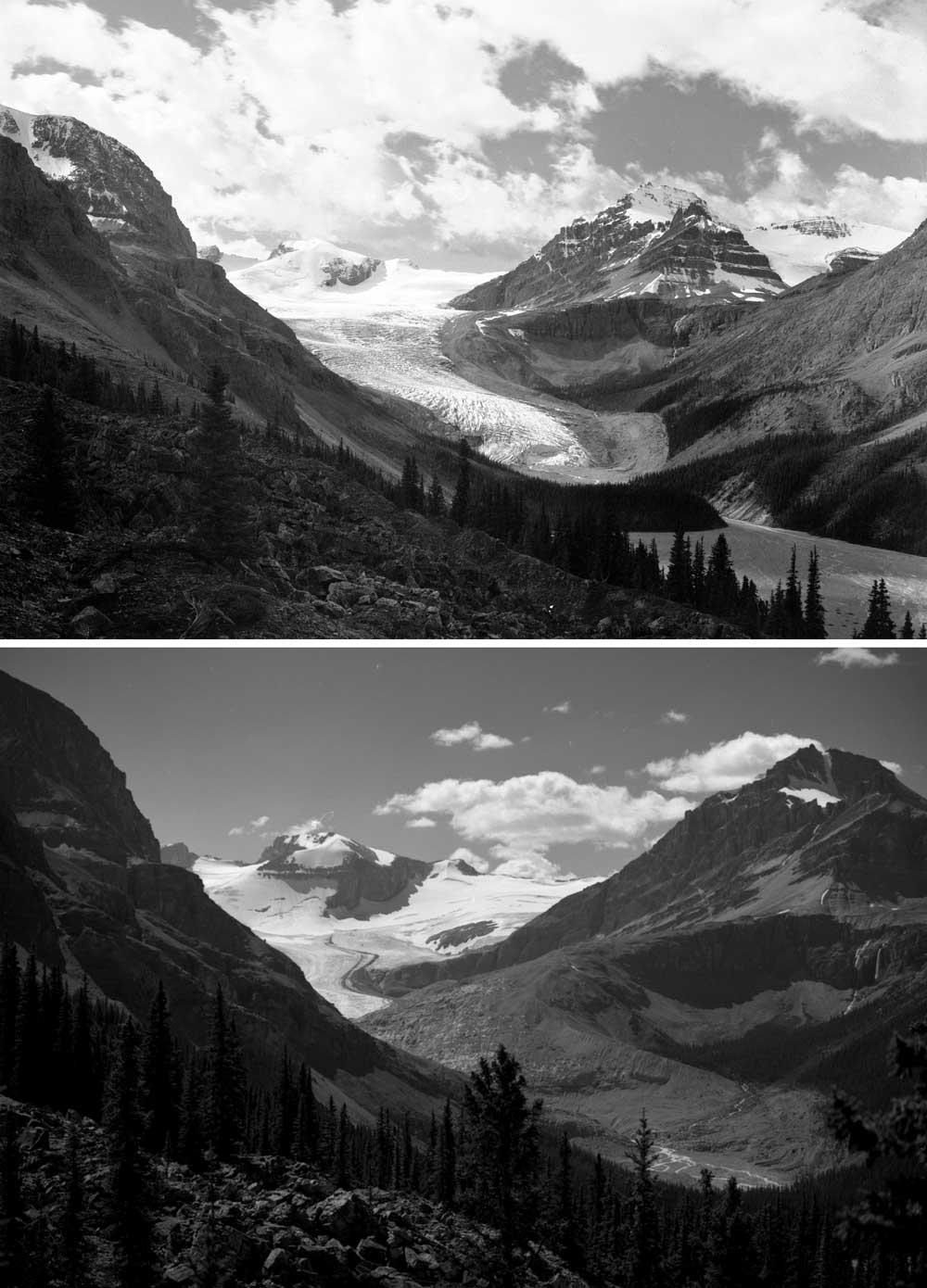

Top: Peyto Glacier, 1902. Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies, V653/NA-1127. Bottom: Peyto Glacier, 2002. Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies.

Aubry-Wake’s work and that of other researchers all contribute to the Peyto’s valuable role as the North American glacier that has been continuously studied the longest. The first photograph of the ancient ice tongue was captured in 1896 by American explorer Walter Wilcox. The lake was known then as Doghead Lake—exactly what it resembles from any high point near its south end looking north. Wilcox renamed it for his guide/outfitter, Bill Peyto, who would later become one of Canada’s first national park wardens. First published in National Geographic magazine in 1899, Wilcox’s image shows the glacier extending nearly to the lake, providing a reference point that remains valuable today.

The first scientific studies recording the glacier’s position began in 1933, and from 1945 to 1960 Peyto was among several of the Rockies glaciers regularly surveyed by the Dominion Water and Power Bureau, which became the Water Survey of Canada. Peyto’s role grew when it was included among five glaciers in western Canada to be mapped and extensively measured annually from 1965 thru 1974 as part of Canada’s contribution to UNESCO’s International Hydrological Decade.

With the viewpoint parking area just a 30-minute drive from Lake Louise up the Icefields Parkway, Peyto Glacier retains its status for two main reasons. “First of all, it’s accessible. It’s not that easy to get to, but it’s easier to reach than a lot of other glaciers in the Rockies: just a three-hour hike in,” Aubry-Wake explained. “The second reason is historical. This glacier has been studied for so many years, and so many different projects have been done in that location. There’s a lot of data and information on that environment. It’s quite rare to have such a long data set to build upon.”

Temperature records in the Rockies were surpassed in summer 2021 not by fractions of degrees but by as much as 3ºC and 4ºC.

That extensive information base proved especially relevant in the summer of 2021, when temperature records were surpassed not by fractions of degrees, as is usual with such records, but by as much as 3ºC and 4ºC. In the town of Banff, where records have been kept since 1887, the temperature reached 37.8ºC on June 29, beating the previous high of 33.9ºC set in 1937 (during a prolonged drought known as the Dirty Thirties). Peyto Glacier’s melt rate was soon far surpassing the 25-metre annual average for the previous quarter century.

“It melted so much and so fast,” Aubry-Wake said. “It was incredible—badly incredible—how much change happened in one season. The toe collapsed and it retreated by 200 metres. And because we have years of data, we can put that extreme event from summer of 2021 in context. If we only had data for as long as five years, it would be really hard to quantify how different that summer was.”

In winter, glaciers appear to be asleep when they’re buried under a blanket of snow that conceals their boundaries and crevasses—where shimmering blue ice splits apart where the bedrock supporting the glacier steepens. In summertime, warm temperatures cause creeks rushing with meltwater to flow on the ice surface, making the glaciers seem alive. But when winter snows aren’t sufficient to maintain the glacier’s volume, that lively melt signals that the glacier is dying.

As one of about 1,160 glaciers remaining in Alberta, all found in the Rockies’ eastern slopes, Peyto provides information that’s representative of hundreds of small glaciers that scientists don’t have the resources to study. Data recorded at Peyto, including air and surface temperatures, precipitation amounts, humidity, wind speed and direction and more, is recorded and transmitted via satellite directly to researchers’ desktops at the Coldwater Lab in Canmore and to Natural Resources Canada in Ottawa. In addition to contributing to Canada’s network of studied glaciers and associated freshwater resources, information from Peyto is shared with the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, and with Parks Canada, within whose boundaries the headwaters of Alberta’s key rivers are protected. The data is also shared with downstream industries, including mining, hydro power, irrigation, tourism and ecosystem services. And it’s shared with Alberta Environment and Parks to facilitate water management and allocation decisions.

Draining to the north to feed the North Saskatchewan River, Peyto shares similar characteristics with nearby Bow Glacier, which also descends from the Wapta Icefield. As the headwaters of the Bow River, that glacier contributes to the freshwater supply of Alberta’s most populated region, flowing through Banff, then Calgary with its 1.4 million residents, and on to the southeast of the province, where it joins the Oldman River to form the South Saskatchewan River. The North and South Saskatchewan rivers then merge to course toward Lake Winnipeg and ultimately drain into Hudson Bay. Meltwater from the Wapta Icefield helps sustain no less than three provinces.

Left: Scientists at the Peyto Glacier research station (built in the 1960s) after a day spent studying glacial composition and melt rate. Right: Researchers May Guan, Steve Bertollo and Scott Munro set up monitoring equipment on Peyto. This image was taken in 2011; the ice they’re standing on has since melted and formed a large lake. Photos: Lynn Martel.

When asked how Alberta is preparing for a diminished freshwater supply as a result of our glaciers melting, Jason Penner, communications adviser with Alberta Environment and Parks, replied that “glaciers are a relatively small component of Alberta’s freshwater supply.” “While retreating glaciers are a concern, notably in late summer and in drier years, seasonal and year-over-year variability of precipitation has a much greater impact on water supply in Alberta,” he said.

With less snow and ice will come smaller streamflows. Less water will be available to balance things out during hot, dry periods, when it’s needed most.

When averaged out over the year, the annual contribution of glacier-melt to rivers in Alberta might indeed seem small, as low as 4 per cent. But in late summer, when rainfall is usually at its lowest and all the previous winter’s snow is gone, that number jumps to as much as 30 per cent of river flow. Glacier ice is nature’s savings account for water.

“Summer 2021 really showed the role of glaciers in the regional hydrology,” Aubry-Wake said. “This is exactly what’s useful about glaciers: when it’s hot and dry, they provide more water. That’s the fundamental glacier functionality. They help us to be more resilient to dry periods.”

But extra glacial melt has its limits. The heat in the summer of 2021 resulted in Environment Canada recording 219 daily maximum temperature records broken or tied in Alberta, and 49 provincial sites registering all-time maximum temperatures. Alpine wildflowers shrivelled, thousands of oxygen-starved fish died, crops withered and Alberta reported 66 excess deaths—that is, 66 people here died from the heatwave. Those extreme temperatures didn’t happen in the late-summer weeks, though, but from June 25 through July 7. The following five weeks brought only minimal rain, resulting in the province spending $136-million to help Alberta ranchers with feed and water costs.

By November, water levels in the Bow River were at less than half of the average of all observations recorded in the 125 years the Water Survey of Canada has been measuring the river, said John Pomeroy. As of early May 2022 the Bow remained unusually low. Levels were expected to increase as soon as snow melted at higher elevations and spring rainfall arrived.

“Overall, streamflows from most Canadian Rockies rivers were very high as deep snowpacks melted in the heat dome of late June and early July 2021,” Pomeroy said. “Then [they] dropped to half of normal or lower from mid-July onwards as the drought reduced mountain runoff and depleted groundwater that would feed these rivers. The Milk River in southern Alberta had its natural flow go to zero in July. But glacier-fed rivers such as the Athabasca, Sunwapta and North Saskatchewan stayed with high flows due to rapid glacial melt in the heat.”

With that, Rockies glacier melt reached a critical juncture. “As glaciers disappear, this extra water in drought and heatwave years like 2021 won’t be there,” Pomeroy said. “2021 appears to be a tipping point for some Canadian Rockies glaciers. Air temperatures were the highest ever recorded on Peyto and Athabasca. Algae are growing on the wildfire soot and keeping the glaciers dark, so they heat up in the sun and melt fast. Other, larger and colder glaciers such as Athabasca will soon follow Peyto’s path to destruction.”

None of this is news to Pomeroy. But what did surprise climate scientists—not only in Canada but around the world—about the western Canada heatwave was that those temperatures hadn’t been expected for another three decades.

“What happened in BC and throughout the Canadian West during the summer and fall of 2021 should be regarded as a 9/11 alarm that wakes us all up to the climate emergency,” said Bob Sandford, a Canmore-based senior adviser on water issues and Global Water Futures Fellow with the UN University Institute for Water, Environment and Health. “We’ve known for a long time that this day would eventually arrive if we continued to ignore the warnings and the evidence of the risks we were taking,” he said. “But we didn’t expect that climate change impacts projected to appear by mid-century if we didn’t act now to dramatically reduce carbon dioxide emissions would arrive 20 to 30 years early. The West got slammed.”

While a study published in 2021 by Brandi Newton, a hydroclimatologist at Alberta Environment and Parks, showed that from 1951 to 2017 winter precipitation—from November to April—decreased, “November–April precipitation in the Rocky Mountains is projected to increase in the future.”

At the same time, Aubry-Wake’s modelling work found that overall, looking at data from 2000 to 2090, a decrease in future streamflow is predicted. “We’ll have more rain falling, more snow falling—mostly more rain, because it’s warmer, so less snow overall,” she said. “But we’ll still see a decrease in stream flow of about 7 per cent.”

This is because while snow and ice serve our needs by storing water, when rain falls, water flows away. That leaves less water available to balance things out during hot, dry periods, when it’s needed the most. In short: More spring runoff means shrunken rivers in summer.

Meanwhile, with glaciers all around the planet melting, including the massive icecaps of Greenland and Antarctica, more liquid water becomes available to an already energized water cycle. Climate change, Sandford pointed out, is all about water. “It’s estimated that even at 2°C of warming, the concentration of water vapour in the atmosphere could increase by as much as 20 per cent, with a commensurate increase in its power to further amplify warming,” he said. “We must get control of carbon dioxide emissions so that we can limit the damage and the impacts that water—and, in its absence, drought and fire—can visit on the world. If more people understood this, there might be less resistance to climate action.”

Considering that Alberta has had some of the most expensive environmental disasters in Canada’s history—the June 2013 southern Alberta floods resulted in $1.7-billion in insured damage, while the May 2016 Fort McMurray wildfire cost $3.8-billion plus an estimated $6-billion in uninsured damage—it would make sense, Sandford suggested, for Alberta to be leading the transition away from fossil fuels to more sustainable energy sources.

During the NDP term of office (2015–2019), Sandford said, the MLA for the Banff-Kananaskis riding, Cam Westhead, and Environment Minister Shannon Phillips made several visits to the Coldwater Lab in Canmore. But with the Rockies glaciers melting faster than ever, neither Alberta’s current environment minister nor the region’s latest MLA have shown any interest in the scientists who monitor our water, or in their findings. “Minister Phillips was the last provincial politician, MLA or otherwise, to ever visit us in Canmore or to take an interest in our research,” he said.

Researcher Caroline Aubry-Wake, who studies how soot from forest fires darkens a glacier’s surface and increases melt rate. Photo: Lynn Martel.

Researchers aren’t alone in voicing their concern. Recreational climbers and professional mountain guides, who spend countless days year-round amidst millennia-old ice, season after season, are noticing routes becoming inaccessible. “Our final surprise was the view of the Peyto Glacier from the glacial research station,” wrote Association of Canadian Mountain Guides member Maarten van Haeren in August 2020 in a publicly accessible conditions report. “The glacier has a large new collapse in the centre (about 100 m × 60 m in area and ~30 m–40 m deep), and the traditional access from looker’s right to gain the glacier was a 10 m strip of ice that was not underwater. If I had another Peyto Hut booking, I would approach via the Bow Hut trail. Certainly disheartening to see these drastic changes from last year to this year.”

In 1940 the Icefields Parkway from Lake Louise to Jasper opened to automobiles, having been travelled as the “Trail of the Glaciers” by commercial packtrains for decades. The federally funded project had provided employment during the Great Depression. In 1961 the road was paved and upgraded to its current state. At least a million vehicles from every corner of North America drive it annually, mostly in July and August, their occupants stopping at strategically placed glacier viewpoints. It’s consistently rated among the most scenic drives in the world. Alberta licence plates outnumber those of all other jurisdictions combined. Families large and small disembark at pullouts, reciting the glaciers’ names—Victoria, Crowfoot, Snowbird, Athabasca, Angel—as if rendezvousing with friends.

Glaciers have been part of the Rockies landscape longer than people have—more than 11,000 years. Today we hang photos and paintings of them on our walls; local companies use their proximity to the ice-capped Rockies to attract employees. We boast of “our” Rockies when we travel. And by the time today’s children become parents, they will look to many of these high cirques and hanging valleys and see only rock.

It’s not only our landscape that’s changing, but even our language. Historically, the term “glacial pace” meant something was happening so slowly as to be imperceptible. Not anymore. “It used to be that if you wanted to see how a glacier was changing, you had to go every 10 years or so to be able to notice the change,” Aubry-Wake said. “And now it’s like, oh, three months later.”

Lynn Martel explores and documents the mountain world. Her latest book is Stories of Ice (Rocky Mountain Books, 2020).

____________________________________________