There it is in the Prairie History edition of Spring 2023: “Rabbi Eliezer Gruber’s Jewish Agricultural Settlement Schemes in Manitoba,” by John C. Lehr. It’s a somewhat unflattering account, and I know worse things about the rabbi, including what the family regarded as shameful secrets. Lehr outlines how the community of Gruber, Manitoba, was founded as a Jewish settler colony in 1898 “on the Mossy River a few miles south of Winnipegosis.”

Growing up in the shabbiest part of the North End of Winnipeg in an immigrant home, I was both inspired and confounded by the story of my great-grandfather Eliezer Gruber having been the first founder of a Jewish agricultural colony in Manitoba and a celebrated Winnipeg rabbi. Several times we visited the stunning mausoleum erected to him in Shaarey Zedek cemetery, the largest Jewish cemetery in the city. Meanwhile we were living in a slummy house converted into three small apartments that would be expropriated and torn down by the city in the late 1960s to make room for a public housing development that was never actually built.

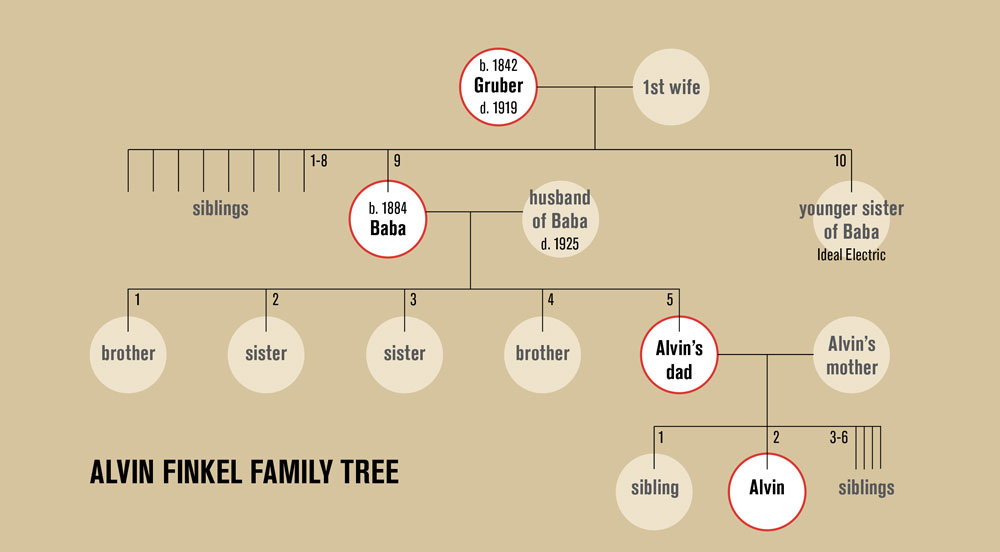

What made no sense to me was how it was that my great-grandfather was such a big macher (bigshot) in Manitoba at the turn of the 20th century, and yet my baba (grandmother) and all her children remained in a mud hut in a shtetl (Jewish village) in Polish-occupied Ukraine until they immigrated to Canada in the 1930s. Cholojow was situated 62 kilometres northeast of Lviv and had a population of 4,151 in 1921, of whom 793 lived in the Jewish ghetto. The story of the family’s emigration from there had Biblical overtones. About 1932, the couple who owned Ideal Electric in Winnipeg prepaid the travel costs for my dad’s two sisters, both in their early twenties, to work in the shop. My baba’s younger sister was the woman of the couple. The deal was that they would work to pay off that travel, assembling lamps, and then start accumulating earnings to bring the rest of the family to Winnipeg. But after a few years the owners decided to make aliyah to Palestine, failing to leave the girls the money they had earned to bring more family members to the city. The new owners, also relatives, said they had not received the saved wages of the young women and they would have to start all over in their effort to bring family out of central Europe. Only in late 1937, when my dad was 15, did he, one of his brothers and baba come to Canada. The interruption in funds to bring family made it impossible to bring the oldest brother, for whom I’m named in Yiddish, along with his wife and child to Winnipeg. They all died in the Holocaust.

My dad, with zero formal education and not a word of English, went to work as a sewer in a shmata (garment) factory. When the Second World War came, he joined the army. His post-war veterans bonus went to providing dowries for his sisters and a house for baba with two one-bedroom apartments to provide her an income. We lived in one of those apartments until I was 9 and my mom was pregnant with the fifth of her six children. At that point my parents bought a dumpy house of their own with a second floor they could rent out to pay a mortgage. My dad often worked three jobs, the main one being a labourer at the CPR.

My knowledge of my great-grandfather Eliezer, apart from the words on his shrine and a few hints from my dad, was restricted to two letters that my dad had inherited. One was from Eliezer to his wife in Cholojow, the shtetl where she remained, in 1880. He warned her that there was no future for Jews in central Europe. “Men vet alle zebrennen,” he wrote in Yiddish letters. “You are all going to burn.” They had married in 1857, when he was 15, but he spent as much time afterwards in Britain, where he learned to speak English, as in Cholojow. He returned home often enough to keep her constantly pregnant, with 10 live children completing the family in the late 1880s. My baba, likely born in 1884, was the ninth child. After Eliezer moved to New York City in 1892 and then Winnipeg by 1898, he apparently continued to write to my great-grandmother, urging her to come to North America along with her children at his expense. The letter from her to Eliezer in the early 1900s proclaimed that the “very soil of Canada is unkosher.” When I read that, at age 15, I said to my dad: “She’s a religious nutcase.” Later I would understand that her statement was only superficially about religion.

Two of the 10 Cholojow children did come to Canada. But I was 30 when I learned why his wife stayed put. Two old crones had twice shooed away my older brother and me from playing near the shrine. “Who were those women?” I asked dad. He laughed: “They’re your relatives.” But I had gone to many extended-family events and never seen them there. “They’re from his other family,” said dad. “The old goat was a bigamist. He had 10 kids with his first wife and seven with the second.” Lehr, who didn’t uncover the bigamy, speaks of only six kids. There was a history lesson in my dad’s revelation. Great-grand-baba did not mean God had fouled the land of Canada; she meant that her two-timing husband had done that.

He went on to make a success of himself. Lehr notes that he was regarded as a wise rabbi by his congregants, even though an article in the Morning Telegram on February 26, 1901, questioned whether he was a rabbi at all and strongly suggested that he was at bottom a conman. Having failed to sell all the land in Gruber to Canadians, Eliezer Gruber visited American Jewish communities and offered to sell town lots for $100 to $200, with one-third to be paid upfront, the rest in instalments. After he sold a lot to a Jewish man in Dubuque, Iowa, the man made a complaint to the authorities, and Gruber was arrested in Des Moines and charged with fraud. A Des Moines rabbi who initially tried to get him released told the Telegram that Gruber was lying when he claimed that he was in the city to preach to the Jewish congregation, not to sell land. Gruber told the newspaper that the complainant was influenced by “lies in Jewish papers published in New York. They don’t like me down there. They are persecuting me…. They can’t stand to see we are building up my colony.” But the Des Moines rabbi told the Telegram, “I don’t believe he is a rabbi at all.” Lehr also notes that there is no evidence of Gruber ever having been ordained and suggests his colonization schemes were motivated by commercial gain, not religion. He required his colonists, who, like him, received free farmland, to purchase land on his unfarmed land to build their houses there rather than on their free land.

When Gruber died in 1919 in Winnipeg at the age of 76 or 77, he was apparently well off. He willed his wealth to his 17 children equally. But family lore is that the nine children in Winnipeg (two from the first family and the seven from the second) collaborated to claim that none of the remaining Cholojow children were still alive. The Winnipeg authorities may have believed that, because during the First World War Jewish wartime conscripts in the Austro-Hungarian army died in large numbers, first during the fighting and then from a plague that followed. My baba certainly survived, but her husband came back to Cholojow from the war, as my dad said, “Not quite right.” He died in 1925, age 36, when my dad was 3. They survived on my baba’s work acquiring chickens from local farmers and then going by horse and buggy to Lemburg (Lviv) to sell them to the Jewish community, who comprised a third of the big city’s population. But they lived poorly, because baba gave half of what she earned to the Talmudic students who, in dad’s view, were social parasites.

Their lack of inheritance may have been a blessing in disguise. Baba’s younger sister was one of the two inheritors from the first family and her money went into the establishment of Ideal Electric. The existence of that firm and her willingness to bring my two aunts to work in the company, if only for peanuts, ended up saving my dad’s family, who might have been less keen to leave Cholojow had they had an inheritance and not been close to starving. So, while great-granddad was likely a conman, his money ultimately explains why my dad’s family did not stay behind and become Holocaust victims. Of course, the land which provided some of that conman income was stolen Indigenous land in a dispossession Canadians still largely deny. So, I’ll thank Indigenous elders along with conman Rabbi Eliezer Gruber for the fact that I ever got to be born at all.

Alvin Finkel is professor emeritus at Athabasca University, co-founder of the Alberta Labour History Institute, and author of Humans: The 300,000 Year Struggle for Equality (Lorimer, 2024).

_______________________________________