The prototype for the ideal contemporary theatre exists and I have seen it. It’s aesthetically pleasing and a marvel of engineering. The acoustics are spectacular. It is able to accommodate thousands of spectators, and its sightlines, regardless of seating, are exemplary. It produces no carbon emissions; the utility costs required to operate it in its traditional manner amount to nothing. And it’s over 2,000 years old.

You can see the theatre too, if you’d like. The Theatre of Dionysus in Athens, Greece, comfortably nestles on a rocky hillside below the Acropolis, where for hundreds of years Athenians gathered during the Festival of Dionysus to view comedies and tragedies. This ancient theatre reminds us, today, of an enormous contemporary challenge. Can we create a theatre as efficient, effective and environmentally friendly as a theatre designed and erected with primitive technology over 2,000 years ago?

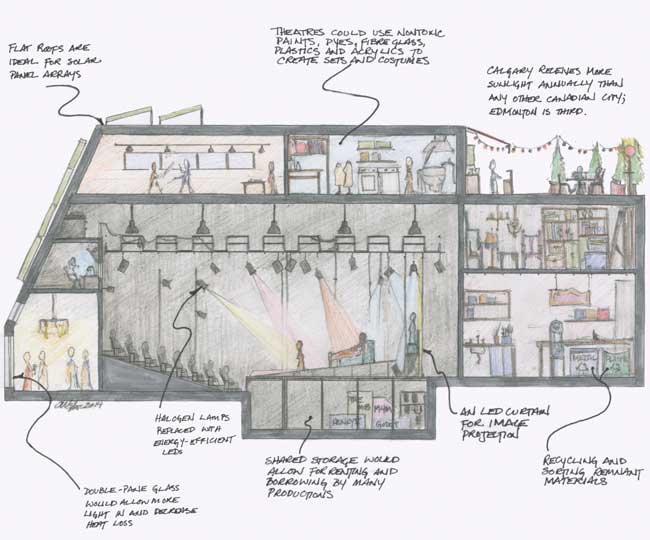

Those of us in the arts tend to view Alberta’s environmental problems as principally the responsibility of Big Industry. After all, theatre doesn’t require a smokestack or a tailings pond. However, the energy requirements of the typical theatre are by no means negligible. Utility costs aside, theatres use all sorts of toxic substances—paints, dyes, fibreglass, plastics and acrylics—to create sets that often end up in landfills.

Is it possible for a contemporary theatre to walk its environmental talk? If the stories presented in the theatre are intended to truly inspire, shouldn’t the way they are produced and presented inspire as well? Can the contemporary theatre move in the direction of a greener theatrical lifestyle, and if so, how?

Two central environmental issues confront every theatre: waste management and energy consumption. Theatre creates waste because of its temporariness—new shows are constantly built and then dismantled. Depending on the particular design, theatres can erect and discard the equivalent of a small house with each production. As for theatre’s energy consumption, part of the challenge arises from the discipline’s visual nature. Audiences pay to see what happens on stage, and if they are to see well, a theatre needs lights, and lots of them.

I asked University of Calgary director of theatre production Don Monty if theatre lights consume as much energy and heat as they appear to. He was succinct: “When we are in production, the lighting system consumes the most energy on a weekly basis. We are in production for about six to 10 weeks per year. The average lighting hang in our theatre consumes between 100,000 and 160,000 watts for two to four hours daily per production period. How much heat those lights generate, I can only put in layman’s terms—a ton.”

Given these difficulties, is it feasible for theatres to reduce energy consumption, reduce waste and consequently leave a lighter environmental footprint?

Penny Ritco, executive director of Edmonton’s Citadel Theatre, described the strategies her theatre has adopted. “The majority of our cleaning products are low-toxicity solutions. We have building-wide recycling collection for general office waste, and we’ve hired a waste disposal company that sorts our construction waste at its facility, diverting anything recyclable away from the landfill.” This sounds like a responsible approach for a huge entity like the Citadel, home to many theatre companies, although it invites the question of what percentage of material the disposal company actually manages to divert from the landfill.

Waste disposal poses just as pressing an issue for smaller theatres, but stringent budgetary considerations may rule out hiring waste-disposal services or diverting valuable work hours to sorting through remnant materials. So what’s to be done? Calgary theatre designer and U of C professor April Viczko suggests pooling resources and promoting a community-coordinated approach. “A movement for theatre recycling keeps surfacing,” Viczko says. “A centralized storehouse would deposit items from shows, to be rented or borrowed by other productions. One of the main reasons so much of what we make ends up in the landfill is that theatres don’t have the space to store it all; and in the current economy, it’s cheaper to buy new or make new than to store costumes and set pieces. Perhaps bulk shared-storage in every city is the answer.”

Illustration by April Viczko.

As for finding solutions to our theatres’ energy consumption, I asked Monty if it would be possible to reduce energy output by replacing the hot, energy-guzzling tungsten halogen lamps with cooler, longer-lasting, more energy-efficient LEDs. He responded with a definite “maybe.” Monty noted that the U of C’s Reeve and Matthews theatres had already received a number of smaller LEDs and would likely obtain more, but he expressed reservations about transitioning to a full complement of LED lighting, saying the technology is still evolving.

Ritco shares those reservations. “Lighting-wise, the industry has come leaps and bounds in LED theatrical fixtures,” she says, “but they still don’t offer a complete replacement for the old tungsten fixtures, and it isn’t practical to do a straight swap of tungsten fixtures for LEDs. Good-quality fixtures are very costly, so it’s difficult for a not for profit, on a budget, to justify making the switch, even if that switch will ultimately reduce their power bill.”

Viczko says there’s another wrinkle. “The initial investment in new lighting instruments is one thing. But the conversion of a theatre to LED isn’t cheap either,” she cautions. “Why? Because LEDs use DC, not AC. That means essentially all those aging dimmers are useless for an LED lighting rig. So, you can’t just change the dimmers, you’ll need to change your entire lighting system. That’s big bucks.”

So if lighting can only be modified as the technology catches up, what can theatres can do in the meantime? York University professor Ian Garret’s special research interest is environmental theatre, and he frames the situation in a slightly different context. “Studies show that for most theatres the biggest energy hog is actually everything around the performance space,” he says. “Front of house [lobby, box office, concessions and so on] consumes about 30 per cent or more of the energy used in operating theatres. Administrative offices, costume shops and rehearsal spaces rank up there as well. Though theatres use powerful lights— and lots of them—it’s rare to have them all on, or for them to be all the way on when they are.”

While cooler, more energy-efficient theatre lights are desirable and possible as the technology advances, theatres may be able to wean off energy consumption through the pursuit of everyday energy efficiencies. Ritco notes that the Citadel Theatre has taken steps in that direction. “The facility uses energy-efficient light bulbs wherever possible,” she tells me, adding that during recent renovations “every effort was made to keep energy efficiency at the forefront of the planning. The old, poorly insulated lobby glass was replaced with more efficient, double-pane, less-reflective glass to allow more natural light into the lobby spaces [reducing the need for artificial light during the day] and decrease loss of heat in the winter.”

It seems, then, that short-term and medium-term options are available. Monty proposes a longer-term solution. “Many theatres,” he points out, “have vast, flat roof surfaces that seem ideal for solar panel arrays that could supplement our imprint on the electrical grid.”

He raises an excellent point. The potential to apply solar power to urban workspaces has been underacknowledged in North America. According to the latest report of the European Photovoltaic Industry Association, Europe, with more than 58 per cent of the world’s photovoltaic cumulative capacity, still leads the way. Yet solar power has proven enormously useful in servicing applications such as heating and cooling spaces. If, in fact, the ancillary needs of a theatre draw the greatest amount of energy—heating and cooling the lobby and the costume shop, for instance—then solar power could prove extremely helpful. Alberta actually enjoys a prodigious number of sunny days. Based on weather data collected from 1981 to 2010, Calgary, with a fabulous 2,396 hours of sunshine, receives more sunny hours annually than any other major Canadian city. Edmonton, with 2,345 hours of sunshine, is third, after Winnipeg.

Clearly there’s some initial movement towards a green theatre. Solutions are being explored. But a number of the solutions are largely stymied by start-up expenses. Ritco sums it up: “Cost is the biggest barrier on all fronts in attempting to become more ecologically conscious.”

Two central environmental issues confront theatres: waste due to temporariness and energy use owing to the discipline’s visual nature.

Government could take a stronger leadership role. The province already is, in a sense, a financial partner with many arts entities, in that grants account for a good portion of such organizations’ operating budgets. A program that underwrote startup costs for energy-efficient changes would be good for the environment, good for the theatre and ultimately good for taxpayers. Many theatres could benefit from better insulation, and if they were also retrofitted with solar panels, could provide low-cost heat for their spaces.

Looking to the future, is it possible to envision a time when theatres could be operating off the grid and not adding to greenhouse emissions? “A completely green, zero-footprint theatre still seems a long way off,” says Viczko. “Maybe this [kind of initiative] could be viewed as a special project. We could attempt one green production a year.” And perhaps an incremental strategy is best. One green production, or perhaps one green production season per theatre, might be an exciting and informative exercise.

Garret strikes a more positive stance, however. “We can expect to see one of our A houses go off the grid one day,” he says. “Between the rapid advancements in technology, which will allow for energy to be conserved, and through the addition of solar, wind or other renewable energy technologies to our theatre facilities, it’s just a matter of time. And when you consider that theatres are only using [their facilities] part of the time, these might be some of the best buildings to feed energy back into the grid when they aren’t in use!”

I find that a fascinating and invigorating vision. A time in the future when theatres have been modified to recycle materials and diminish energy consumption, and are equipped with the tools to generate alternative energy in quantities great enough to supply their own needs, or even sufficient to sell back to the grid.

In a sense, my original comparison of an ancient Greek theatre to contemporary buildings could be viewed as relating apples to oranges. The energy requirements of an outdoor theatre in a Mediterranean climate are bound to be vastly different from requirements of a theatre located in a colder environment.

And yet lessons can be drawn from our predecessors. Greek theatres were built from materials that were meant to endure—and they have. Wherever the ancient Greeks went—Sicily, Macedonia, Turkey—you will still find remnants of their facilities. There were no electrical options, so the architects made the best use of their environmental situation. Theatres were constructed to fit neatly into the contours of the existing terrain. It was expensive and time-consuming to recreate materials for performances, so certain elements—masks and costume pieces—were reused from one performance to the next. There was a sense of simplicity and economy and elegance to the work.

In terms of production, the Greek theatre was a simpler theatre, yes, but not necessarily a less effective one. Our contemporary notions of theatre demand that each production maintain an elaborate, individual and disposable visual component, but if we first adjust our aesthetics to expect something simpler, and at the same time pursue responsible solutions of engineering and technology, we may yet be able to achieve a greener theatre.

Clem Martini is an award-winning playwright, novelist and screenwriter who has written over 30 plays and nine works of fiction.