A decade ago, when Alberta was debt-free and staring at a $7.4-billion surplus, Premier Ralph Klein decided it was time to spread the wealth. He announced that every person who lived in the province—and, as it turned out, more than a few who didn’t—would receive a cheque for $400 as a “Prosperity Bonus,” a $1.4-billion giveaway that quickly became known as “Ralph Bucks.” Former premier Peter Lougheed, the architect of the province’s long-neglected Heritage Fund, disagreed with the move. In an open letter in the Calgary Herald on February 16, 2006, he wrote: “If we do not save a sufficient portion of these oil and gas revenues, history proves that much of it will be dissipated on non-essential expenditures and we will not have much to show for it 10 years or so from now.”

Lougheed argued that the province ought to be socking away at least a third of its annual resource revenues for the future. But his call for restraint was duly ignored, and there was even talk of another round of Ralph Bucks in 2006. After all, gas and oil prices were soaring. The province was sitting on likely the single largest reserve of crude on the planet, and most experts were predicting a decline in the rest of the world’s supplies. What could possibly go wrong?

As it turned out, just about everything. The 2008 financial crisis, the worst since the Great Depression, was soon followed by a collapse in natural gas prices across North America. Alberta’s government had raked in $8.4-billion in natural gas royalties in 2005, but in 2009 it collected just $1.5-billion. In 2014 an aggressive Saudi play for market share drove the price of oil down below $40—and pushed prices for Canadian heavy crude far lower than that. Growing environmental concerns transformed the oil sands from an unrivalled asset to a potential liability.

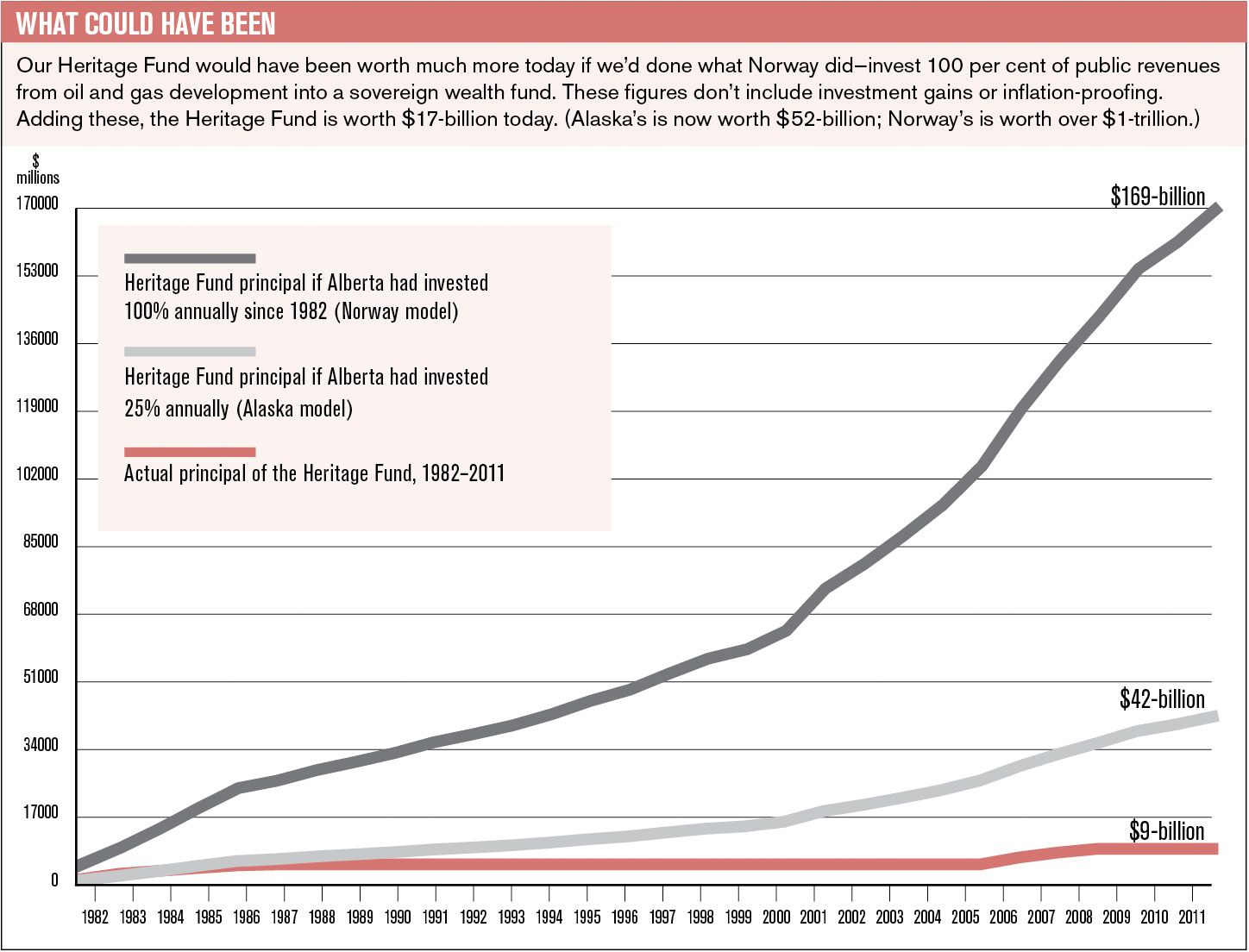

In a province where pissing away the proceeds of commodity booms is a shared pastime, the last 15 years were a Hall of Fame performance. Since 2000 the province has collected almost $144-billion from the sale of oil and gas resources. Total deposits to the Heritage Fund? Just $2.9-billion. Meanwhile, between 2000 and 2011 the entire net income of the Heritage Fund was transferred to the provincial treasury in five of those years, while in another four at least 67 per cent of its earnings was used to fund day-to-day expenditures. As a 2013 Fraser Institute study noted, “Even in 2006 and 2007, when large deposits were made into the Heritage Fund, the government transferred out most of the net income, mitigating the benefits from the contributions.” As a result, the Heritage Fund, which had a balance of $12-billion when Klein announced his giveaway, had grown to just $17.9-billion as of June 30, 2015. In late October the new NDP government announced the biggest budget deficit in Alberta’s history—and an end to any hope of saving money in the Heritage Fund for the foreseeable future.

It wasn’t supposed to be this way. In 1976, when Peter Lougheed’s government created the Alberta Heritage Savings Trust Fund and seeded it with an initial deposit of more than $2-billion, it looked as if it would be able to live up to its pledge to save 30 per cent of the province’s non-renewable resource revenues. Oil prices were on the rise, the province’s production was growing and the government had more tax revenue than purposes to spend it on. But by 1983 those conditions had changed markedly. A sharp fall in global oil prices ate into revenues, so the province scaled back its contributions to the Heritage Fund. Between 1983 and 1987 the contributions were cut in half, to 15 per cent of non-renewable resource revenues. In April 1987 they were suspended indefinitely.

The Heritage Fund had design flaws from the start, with three different—and at times conflicting—objectives.

Our $17.9-billion fund is puny compared to Alaska’s and Norway’s ($72-billion and $1.1-trillion, respectively, in Canadian dollars), but not entirely because of Alberta’s fiscal profligacy. The Heritage Savings Trust Fund had design flaws from the start. It had three different—and at times conflicting—objectives: to save for the future, to strengthen and diversify the economy, and to improve the quality of life of Albertans. The second objective was set aside in 1997 in favour of saving. But the variety of objectives in its first 20 years made it difficult to pursue any one effectively.

An even worse design flaw of the Heritage Fund was the decision to make contributions voluntary and subject to political approval, and to give those same politicians access to the investment income it generated. In his 1991 paper “The Politics of Plenty: Investing Natural Resource Revenues in Alberta and Alaska,” Athabasca University’s Peter Smith summed up these flaws: “While in principle the Legislature would ‘control the tap,’ the cabinet was given the authority to invest and manage most of the fund’s assets without prior approval of the Legislature. This left the fund’s direction in the hands of politicians, exposing it to the vicissitudes of political life in a way that the Alaska fund never was.”

The Alaska Permanent Fund is a useful point of comparison, given that it too was created in 1976 by a subnational government with a growing flood of non-renewable resource revenue. It’s a much more useful comparison than Norway’s massive fund, which is routinely used to criticize Alberta for its failure to save its oil and gas wealth. Norway, after all, has the advantage of being a nation rather than a subnational level of government as Alberta and Alaska are. Norway is geographically and culturally homogeneous, with full access to tidewater, and its people are willing to tolerate a high level of taxation and state involvement in the economy. While many Albertans still recoil in mortal terror at the concept of a modest sales tax, Norwegians pay 25 per cent on most goods and services. And while the government of Alberta is constitutionally obligated to play the role of middle man between a perpetually stingy federal government and increasingly cash-hungry municipalities, Norway has no such difficulties. Alberta has about as much to learn from Norway as Rachel Notley does from Ralph Klein.

Alaska, on the other hand, has much to teach us. After watching the state government receive—and quickly spend—nearly a billion dollars in revenue generated by the sale of Prudhoe Bay leases in the early 1970s, Alaskans realized that the state’s ongoing oil-related windfall needed to be managed with more care. As Smith noted in his 1991 paper, the state’s experience “provided Alaskans with a stark lesson of how swiftly large sums of money could disappear if state spending habits were not restrained by some mechanism. The result was a consensus that part of the forthcoming revenues from the giant Prudhoe Bay field be placed in a permanent fund.” In 1976 Governor Jay Hammond proposed a constitutional amendment that would create the Alaska Permanent Fund and require the state to place at least 25 per cent of its annual oil revenues in it. The state’s legislature put the measure to a referendum in 1976, and it passed by a two-to-one margin.

While Alaskans agreed that a savings fund was needed, it took three years for their state’s politicians to decide what they wanted to invest it in. Alaska’s Senate tended to support economic development, while its counterparts in the House believed saving for the future was a more efficient way to deploy the funds. The House also argued that the pursuit of economic development objectives in a state with just 500,000 residents would invite corruption and inefficiency. In the end they won out, and in April 1980 legislation was passed in both houses that committed the fund to saving for the future. According to Smith, this gave it a clear advantage over the Heritage Fund. “Whereas the Heritage Fund was intended to pursue competing objectives, the Permanent Fund struck out in a singular direction. Its primary objective, to be a savings account, gave it a clarity of purpose that the Heritage Fund has never achieved, and simultaneously facilitated public accountability and support.”

This accountability and support in Alaska was buttressed by the introduction of an annual dividend that paid out $1,000 to every resident of Alaska in 1982 and continued to grow in subsequent years. The dividend in 2015 was $2,072. Unlike Alberta’s one-off prosperity bonus, which was an ad hoc response to an overwhelming surplus of resource revenue, Alaska’s dividend comes from the realized income of their Permanent Fund. The dividend was intended to create a sense of ownership of the fund on the part of Alaskans—and prevent future governments from spending it. “Hammond felt dividends would ensure not only that all Alaskans would be beneficiaries of the state’s wealth,” Smith writes, “but also that there would be a constituency created with an interest in protecting the fund.” It worked, too. In 1999 Alaskans were asked in a ballot question if they wanted the government to be able to use a portion of the Permanent Fund to balance the state’s budget. The advice the government received was unambiguous: 83.25 per cent voted no.

In Alberta, of course, the government has been using its flow of non-renewable resource revenue to balance the budget for years. While the government stopped making deposits to the Heritage Fund in 1987, it had already been dipping into its investment income and using it to fund government expenditures since 1982. In the 1985–86 fiscal year, $1.67-billion was transferred out of the fund and into the provincial treasury—the equivalent of two months of budgetary expenditures. This became a habit: between 1997 and 2011 the Alberta government transferred $29.6-billion of the $31.3-billion in net income generated by the Fund’s capital into its own coffers. As a result, the Fund’s value hasn’t even kept up with inflation. Its per capita value has been declining since the mid-1980s.

Where has the money been going, then? In large part it’s been used to underwrite Alberta’s generous tax regime, which effectively represents an implicit—albeit hidden—dividend for Albertans. “The mantra, especially since Ralph Klein, was no new taxes, cut taxes to the lowest possible level and spend our oil and gas wealth,” says Mount Royal University political science professor Keith Brownsey. The fact that Klein racked up electoral majority after electoral majority speaks to the political success of this strategy, but it also put the province in an ideological straitjacket. “It almost becomes a sacred cow, that thou shall not have a sales tax or thou shall have the lowest income tax in Canada,” says Greg Poelzer, a professor in the University of Saskatchewan’s School of Public Policy. “And when that becomes part of the political culture, it’s hard to change. People don’t really know the extent to which those resources have been subsidizing the lack of a provincial sales tax.”

Conservative politicians have long touted the so-called low-tax “Alberta advantage.” But according to the 2011 report of the Premier’s Council for Economic Strategy, “the true Alberta advantage is not the ability to create a low-tax environment by underwriting a significant proportion of government services with funds received from the sale of energy assets. Rather, the advantage lies in our opportunity to use the proceeds from our natural resource wealth—in combination with our highly educated and skilled people—to intentionally invest in shaping an economy that is much less dependent on natural resources. The practice of spending this converted capital as if it were ordinary income deprives Albertans of the opportunity to intentionally shape our future.”

That wasn’t the first time the government had been told to start planning for a future less dependent on natural resources. In 2007 an advisory committee chaired by the University of Calgary’s Jack Mintz set an ambitious target for the Heritage Fund: $100-billion by 2030. They recommended “a fiscal adjustment” to make that possible. “Alberta’s non-renewable resources should provide significant benefits not just to Albertans today, but also for our children and grandchildren. When our stock of non-renewable resources dwindles, Alberta’s economy will need to rely only on its people—not its natural resources—to create wealth. Alberta should not look like a ghost town in the next century when the resources are depleted.”

Today the Heritage Fund’s balance isn’t appreciably larger than it was when Mintz and his colleagues tabled their report. It’s one thing for a panel of academics and experts to propose an overhaul of the tax regime, and quite another—suicidal, most likely—for a government to actually do it. “Just think what happened to the government that introduced the GST at the federal level,” says Leo de Bever, former CEO of AIMCo, the Crown corporation that manages the Heritage Fund. “It was the right decision from a structural point of view, but it was politically very unpopular. This is the problem with democracies: they always want things both ways. They want a lot of services and they want that long-term resource revenue, but they don’t want to pay for it in the short run.”

Alberta’s NDP government may have already learned that lesson. “We saw what happened when this government announced they were going to increase the income tax in certain areas,” de Bever says. “I think if you were to take one more step and consider a sales tax, the politics of it would be very bad. So the question is: If doing the right thing doesn’t get you re-elected, then how is it going to get done?”

Doing that right thing is particularly difficult in Alberta, Poelzer says, given the proportion of its population that lacks long-term roots in the province. “In a place like Saskatchewan and Newfoundland, where the vast majority of the population is intergenerational, you can build that commitment to defer. They want to see their grandchildren and great-grandchildren benefit, so it’s an easier sell there—and a more challenging sell in Alberta.”

But that sell should get easier, given a multipartisan consensus that Alberta’s approach to spending and saving its resource revenues isn’t right. Both the Fraser Institute and the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, two think tanks that couldn’t be farther apart on the ideological spectrum, published recent reports emphasizing the need for Alberta to save more of its resource wealth. That will almost certainly require a major reassessment of the province’s attitude toward taxes, and Poelzer thinks now is the perfect time. “With the crash in oil prices, it does send a shock and a wake-up call that if there is an opportunity to reset the dial, now is the time to do it. If I were advising premier Notley, I’d tell her to proceed with that.”

Rob Roach, a senior analyst with ATB, also thinks the current environment offers an opportunity to radically rethink Alberta’s fiscal structure. “We can almost say, ‘What if we didn’t have any [resource revenue]?’ How would we fund things? What would we cut? What would we increase, in terms of taxes?’ We should start with saving 100 per cent right away, and then justify why it should be less than 100 per cent. What we’ve done in the past is started with 0 and said if we can get it up to 5, 10, 15 or even back to the great Lougheed days of 30 per cent that would be better. But you could reverse it and say, ‘Instead of better than nothing, how do we justify less than the ideal?’” Roach thinks that a citizen’s assembly, one in which Albertans were presented with the various options and information on each, might offer their politicians a way out of the corner they’ve effectively been painted into by their predecessors. “That would solve the problem of leaving it in the hands of politicians who have to face elections—and the electorate—so often,” he says.

The importance of taking it out of the hands of those politicians was underscored in the NDP’s October budget. Despite the difficult environment in which it was drafted and the doors that could have opened to trying new ideas and approaches, the budget was instead a study in the status quo. There was no sales tax and no introduction of any other meaningful new revenue tools. Instead, it simply increased borrowing and spending, but did little to address the same fundamental imbalance in the province’s finances as when Don Getty was racking up similar-sized deficits. In an interview with the Calgary Herald’s James Wood, Notley hinted that the Heritage Fund may become more of a priority in future budgets. “We have not valued it as much as we should have over the last couple of decades,” she said. But this wouldn’t be the first time that a politician has paid lip service to the importance of the Heritage Fund without doing anything to actually increase its balance. “This is about putting the economy in a better position in the longer term,” de Bever says. “But that’s unlikely to happen. What’s likely to happen is that people will say it needs to be done, but not now—now is not the time.”

Pissing away commodity booms is a shared Alberta pastime. The past 15 years were a hall of fame performance.

If there were ever a time, though, it’s now. After all, in a province where praying for the next boom might as well be the state-sanctioned religion, it doesn’t look like we’ll have many more of them to squander. A November 6 Bloomberg story said, “2015 may very well be remembered as the beginning of the end, with the rejection of Keystone and the investigation of Exxon [for withholding information about greenhouse gas emissions].” It’s now a matter of sustaining demand. “You don’t need to be a genius to see where the global trend is heading around energy sources,” Poelzer says. “There literally will still be oil in the ground, and nobody’s going to be buying—not in the quantities we’re seeing. So unless we bank these assets when we sell them, and turn them into financial capital assets, we’re going to pay a big, big price in the long term.”

De Bever is even more bearish on the future of fossil fuels. “A lot of people in the industry would disagree with me, but I believe that burning natural gas and burning oil in a car is a technology that might last 20 years. Then we’ll come up with better ways of doing it. People think I’m nuts, but the growth of wind and solar and battery technology is exponential, and the cost of those technologies is coming down at a good clip. This discussion has to get going, because it’s very unlikely that resource revenues will come back very sharply or very quickly.”

If Alberta is going to leave a legacy for future generations that isn’t limited to truck nuts and tailings ponds, we’ll all have to get accustomed to higher taxes and lower government spending. The combination might be too toxic for any politician with designs on getting re-elected. “It’s a choice between maximizing the welfare of an entity called Alberta versus maximizing the welfare of a generation that happens to be there when you extract the resource,” de Bever says. “And that’s the fundamental choice.”

Which will we make?

Max Fawcett is the former editor of Alberta Oil and former managing editor and Calgary bureau chief for Alberta Venture.

____________________________________________

Support independent local media. Please click to subscribe.