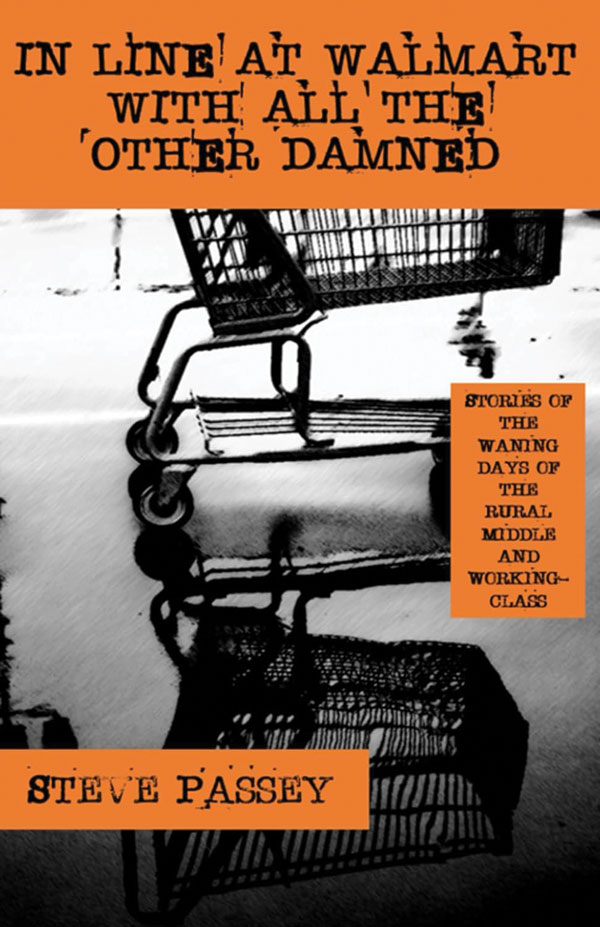

Pick up Steve Passey’s latest book of short stories, In Line at Walmart with All the Other Damned, read a few pages, and most likely you’ll immediately have a question: “Why have I never heard of him before?”

There’s no good answer to that question—the Taber-based fiction writer and poet has been published widely in magazines and anthologies, and has released three previous books, both fiction and poetry. Maybe his dark, at times painful, stories just aren’t the sort of thing that gets writers into Canada Reads or the ever-shrinking books section of The Globe and Mail. It’s a goddamn shame.

“It’s a goddamn shame” could be the epigraph for most of the stories in this book. Passey writes about what might be called the gritty side of life—the characters in his stories, like those of Mark Anthony Jarman or Cormac McCarthy, have little to lose and, as the saying goes, “few illusions.” Except there’s no such thing as somebody with no illusions, and everyone has something to lose. Passey’s gift is showing us the importance and the beauty of the lives we might prefer to characterize with a patronizing word or two and then move on.

Take “The Mick”—a story about a skinny, not exactly bright, would-be boxer whose big achievement is successfully sparring with a woman (he can’t spar with men because he’s too underweight for the other guys at the gym). You could tell the story from the point of view of an observer and make it a minor tragedy. You could tell it from the same point of view as a bitter comedy. Or you could tell it from the boxer’s point of view, as a triumph. Passey takes all these approaches simultaneously, leaving the reader with the feeling God might have been looking down at one of his weak, put-upon but touchingly happy creations. There’s pity, sure, but there’s love.

Passey’s love extends from his characters to their stories, and from his stories to the way they tell them. One of the pitfalls writers of the gritty fall into is either hewing so closely to realism that their characters’ voices—the voices of society’s left-behinds—crystallize into caricature rather than blossom into personality. The opposite is true sometimes—we end up confused by high-school dropouts whose voices sound like those of an MFA student. Passey breezes between Scylla and Charybdis to craft voices that stretch credulity but never break it. A retired railway worker with a gun called the ROCKY MOUNTAIN BEAR FUCKER says, philosophically, “Animals, indifferent to suffering, hunt for sustenance,” and we believe that’s how we talk. It’s unlikely. It’s in character. It’s real. It’s beautiful. Welcome to Steve Passey’s world.

Alex Rettie is a long-time reviewer for Alberta Views.

_______________________________________