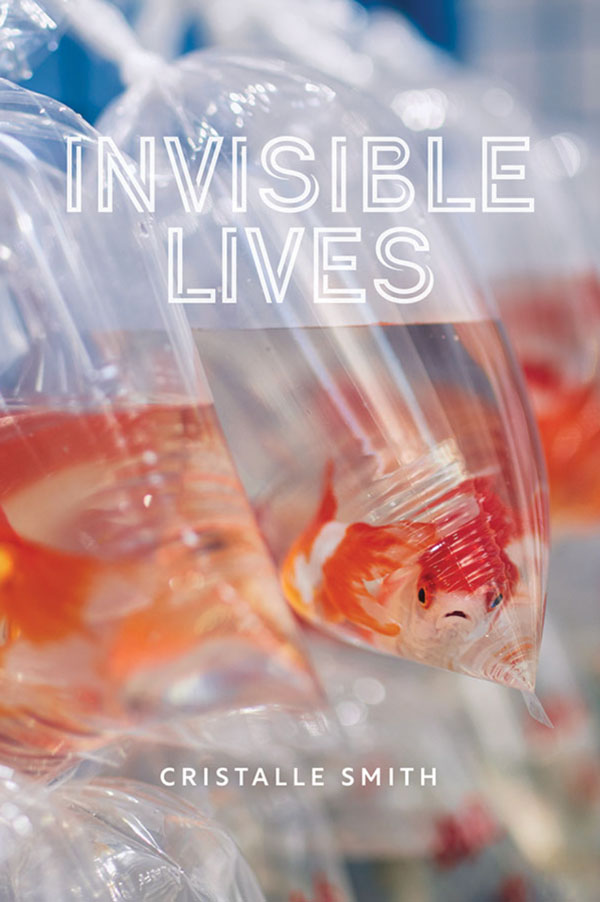

How do poetry and lyric language sort trauma into meaningful pieces of discourse?” This question in Cristalle Smith’s “Lyric Lab Report,” from her searing debut Invisible Lives, could serve as the crux of this entire collection. As could the admission that she is “a scientist, scholar, artist, and mother. I am all things at once. My poetry is all things at once. It is only though the layering of constituent parts that resonance is achieved.”

My caveats on the book are few—mainly that the text-style exchanges between identities such as Submissiveattack and Flakjacketblitz feel out of place and also, strangely, dated, and that at times an excess of details can bog down in prosaic listing. But overall Invisible Lives is a brave and startling assemblage of admissions of abuse, neglect, recklessness and rejuvenation.

Beginning a book with the widely spaced lines “In 2012 my ex-husband tried to choke me to death while I was sleeping./ I was 23 years old,” takes the reader powerfully in from the get-go without apology, and the text rarely relents. Smith is highly adept at the vivid descriptor and her sensory evocations of childhood’s abject poverty are brutal: “Cockroaches scurried over my face…. I slept on mouldy green carpets with my little sister. My mother’s belly grew round with pregnancy.” The piece “Ladybug, ladybug” is a creepy triumph of staccato revelations that make even an act of nature seem unforgiveable: “I hunt aphids to bring to my carnivorous beetles in a margarine tub. I close the lid. They eat them up.”

Akin to the work of Beth Goobie, Elizabeth Bachinsky or even Frank O’Hara, Smith can sketch a scene’s mood fast, scarring the reader with place, sexuality, the relentlessly unheimlich quotidian such as the sonorous “ruffles filled with noodles” or “the vellus hair.” There are pages crammed with text and others that liftoff with white space to give absorptive balance. Chunky prose paragraphs alternate with hewn triplet lyrics. Sometimes the book feels like a violent disgorging; other moments it’s a scraping of the surfaces of what was.

Experimental, innovative and stark, Invisible Lives is an unforgettable first book—even when it has instances of over-the-top rattling off—and the concluding acts of homage to those who shaped her central pieces such as “Fragments of Ficus” deepened the contexts of these compositions. The linkages between abuse, addiction, mental illness, poverty and neglect, but also science and art and mentors and mothering are key to Smith’s book as she fleshes out a world of painful puzzle pieces that eventually merge into a kind of home found in living on within acts of poetry: “the vehicle that will drive us there.”

Catherine Owen is the author of Moving to Delilah.

_______________________________________