The only sound for miles is tires crunching gravel. Eric Musekamp drives north, home to an address he rarely gives out. He has to be careful: You don’t win many friends in these parts by advocating for farm workers.

“I’m looking at abandoned homesteads in every direction,” he says over the phone, his pickup audibly lumbering as he pulls over. He’s squinting at far-off silhouettes on the southern Alberta horizon like he’s scoping out whitetails. “One over there. Another over there.”

With his partner, Darlene Dunlop, Musekamp formed the Farmworkers Union of Alberta in 2004. By then, they’d been fired from farms for reasons such as giving protective equipment to child labourers or refusing to cut corners while welding a fuel tank. Farmers had withheld their wages and blacklisted them. Their home was vandalized; someone drained the brake fluid from Eric’s half-ton. Their fellow farmworkers continued to die frequently and gruesomely; in Alberta from 1990 to 2009 at least 26 died on the job (and 10 times as many were admitted to hospital with major injuries). Famously, the farmworker Terry Carl Rash, a 52-year-old grandfather, was stabbed by his boss and left to bleed to death in a ditch along Highway 36, the Veterans Memorial Highway.

“Two more homesteads over there,” continues Musekamp. “All the land has been bought up and the buildings just sit and deteriorate. In town, the school’s closed, the stores are all closed, everything’s closed.”

Times aren’t hard for everyone in agriculture, however. Drive west toward Lethbridge and you’ll find Lamb Weston’s potato processing plant, which in 2020 reported $3.8-billion in net sales. And the expanded McCain factory, whose owners recently spent $1-billion adding processing capacity across the world. And the $430-million facility owned by Cavendish, itself owned by the billionaire Irving family.

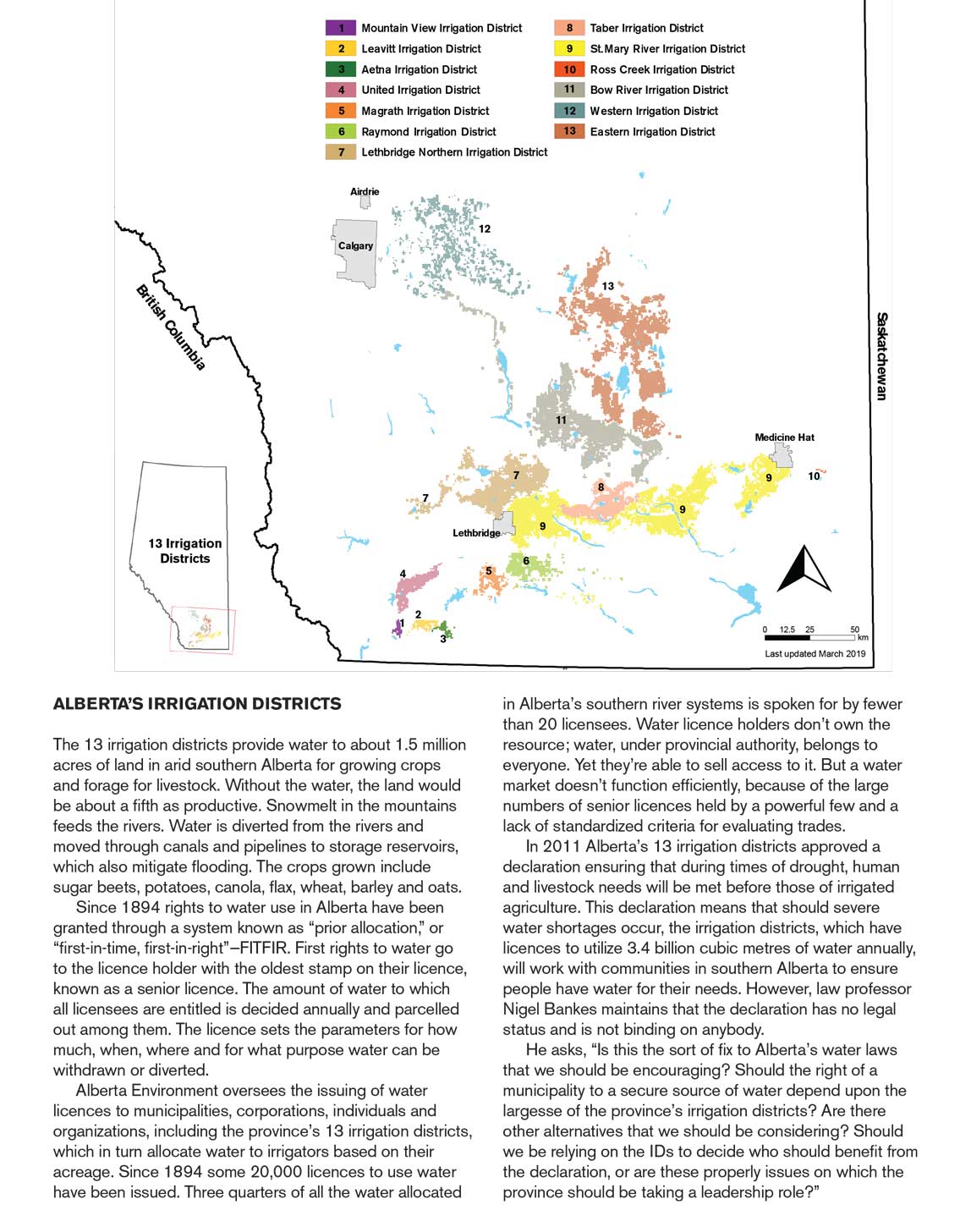

Much of this wealth depends on public infrastructure—that is, irrigation. These canals and pipelines bring water from nearby rivers to more than a million acres of farmland. This part of southern Alberta, while it has rich soil and abundant sunlight, is almost a desert. Without irrigation, the prospects for agriculture here are grim. With it, the desert blooms. A steady supply of water means farmers can grow high-value crops such as potatoes, soybeans and sugar beets. Although less than 6 per cent of Alberta’s farmland is irrigated, irrigation farming adds $3.6-billion to Alberta’s GDP. The entire agriculture sector’s contribution to GDP was less than $6-billion in 2019.

This part of southern Alberta is almost a desert. Without irrigation, the prospects for agriculture here are grim. With it, the desert blooms.

Irrigation farmers fund much of the infrastructure, but the public also underwrites a lot of it. And it’s not cheap: Since 1969 the province has spent almost $1-billion on maintenance alone.

Musekamp has worked on irrigated farms. Yet while public spending on irrigation makes these farms more profitable than ever, workers have continued to struggle. Musekamp and Dunlop have made do with the bare minimum, living through poverty and even homelessness. Farm cash receipts to November grew 4 per cent last year over 2019, but agricultural wages remain 30 per cent lower than the provincial average. From 2009 to 2019 Alberta lost almost 10 per cent of its agricultural workforce. And even as farms are among the most dangerous worksites in Alberta, research suggests farmworkers—due to their lack of legal protection—are significantly underreporting their injuries.

Public spending on irrigation has something in common with the exploitation of workers: Both increase private profits. Since the early 20th century Alberta has exempted farmworkers from basically all employment and health and safety standards, including the Occupational Health and Safety Act and legislation around minimum wages, collective bargaining rights, wage security and working hours. Although the right to organize is enshrined in the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, farm workers in Alberta cannot unionize. “There’s a long tradition of the government allowing employers to externalize costs onto rural communities in order to maintain the short-term viability of industries,” says Bob Barnetson, a professor of labour relations at Athabasca University. “The Alberta government has given agricultural operators a pass on most of the rights that workers would have in any other job.”

So, in October 2020, when the federal and provincial governments announced “an $815-million investment in Alberta’s irrigation network”—the largest irrigation expansion in Alberta’s history—people like Musekamp raised their eyebrows. The outlay is part of the Canada Infrastructure Bank’s COVID-19 recovery plan, which earmarked $1.5-billion for irrigation projects across Canada. Alberta gets the biggest portion, a $407.5-million loan to irrigation districts, by default: The province has 71 per cent of all irrigated land in Canada and uses over 60 per cent of Canada’s irrigation water. The provincial government is contributing a $244.5-million grant, and eight irrigation districts will put in the remaining $163-million. According to its proponents, this investment will boost agricultural profits and increase GDP, increasing yields and creating 6,800 jobs. It will construct four new reservoirs and 56 other modernization projects, saving water while allowing farmers to irrigate more acres. Premier Jason Kenney called it “a slam dunk in one of our economy’s most important industries.”

But any gains from this irrigation expansion will not be distributed equitably across agriculture. In Alberta, corporate profits reign supreme. The “public investment” will not help most farmers or farmworkers, and it threatens to contribute to a degraded environment, water scarcity and further rural decline.

Somewhere near Picture Butte, north of Lethbridge, John Kolk explains how to keep a farm in the family. It’s a rare feat these days. Nearly 60 per cent of Alberta’s farmers are 55 or older. Kolk says your heart has to be in it. His grandfather’s heart was in it; when he arrived in southern Alberta from Holland after the Second World War, he worked on a sugar beet farm and saved money for the 80 acres that became a generational farm. “The Kennedys like politics,” he says, “and the Kolks like farming.”

There’s another factor, though. “I wouldn’t have three kids going into farming if it wasn’t for irrigation,” Kolk says. Although he grows cereal crops on some dryland acres, he has 3,000 irrigated acres for higher-value crops such as specialty seed canola, alfalfa seeds, even corn for export. “The average age of irrigators is lower than the average age of [dryland] farmers on the Prairies,” he continues, “because people see opportunity.” For family farms like the Kolks’, where margins are tight and inputs are more expensive every year, irrigation provides a competitive edge.

This is because irrigation dramatically improves farmland’s productivity. A 2015 study showed that average net returns for some crops increased fivefold because of irrigation. The sales from irrigation agriculture average out to $2,400/ha compared to $329/ha for dryland production. Combine this with access to land, capital and generational know-how, and it would seem more irrigation could help keep family farms like the Kolks’ alive. But the truth may be more complicated.

When the Alberta government announced the irrigation expansion, it said the gains will benefit a large proportion of farmers. Yet only a small percentage of farmers even use irrigation. Meanwhile, farming in Alberta has become highly consolidated; every year, the number of farms decreases but their average size continues to grow. Already, just 6 per cent of farms in Alberta control 40 per cent of the farmland. These larger operations, the wealthiest ones, will benefit most from the irrigation expansion.

The expansion will also keep out new farmers. Irrigation increases productivity, which increases land values. That means a higher cost of admission. In Alberta the price of farmland doubled just in the five years between 2013 and 2018. The highest-value land in southern Alberta, where large operators require irrigation, is almost twice as valuable as that of northern Alberta. The number of young farmers in Alberta has declined by 70 per cent in a single generation.

Further, as climate change threatens the viability of dryland farming, irrigated farmland will only become more valuable. It will become more essential to the region’s large food processors too, which need a consistent, stable supply of irrigation water to buffer against drought years. With operating costs increasing, margins tightening and the price of farmland soaring, more small farms will sell to larger ones. The consolidation will accelerate.

As time goes on, costlier public investments benefit fewer farmers. Meanwhile, people continue to move away and tax bases dry up. Rural schools continue to close. Depopulation accelerates, the average age increases, health outcomes worsen. The sugar beets that Kolk’s grandfather farmed are still valuable, but the Picture Butte beet refinery, which once provided good jobs, shut down in 1977.

It’s easy to see rural decline as inevitable. But rural Canadians have long understood that the decline is the outcome of policy choices. At the same time as people have moved to cities, rural economic development has shifted toward free-market neoliberalism, from agriculture to agribusiness. Under the agribusiness model, the state secures inputs for multinational food processors. Neoliberal governments focus on attracting outside capital, typically by lowering corporate taxes, cutting safety standards and doling out public subsidies. Agribusiness incentivizes scale, so farms expand to chase profits and finance more loans. Yet there’s only so much farmland, so for the profitable farmers to expand, the poorer ones have to leave.

This might be bad for communities, but it’s good for agribusiness. Bankers and economists have long seen family farms as impediments to productivity, pointing out that the top 20 per cent of farms in North America produce 80 per cent of agricultural products. To them, the consolidation involved in agribusiness liberates dormant productivity from the shackles of small, unproductive farmers.

Another challenge: Alberta’s irrigation districts are only allocated so much water, and they’ve effectively reached their limits already. How can the most profitable farmers expand if they can’t get more water? This is where new irrigation projects come in—particularly efficiency improvements. The banner claim for Alberta’s new upgrades is that they’ll allow farmers to irrigate over 200,000 additional acres without using more water. The modernization projects will convert open canal systems into pipelines. By reducing seepage and evaporation, these upgrades will conserve water. Ergo, irrigation districts can water more acres without increasing the districts’ allocations. Efficiency upgrades are why Alberta hasn’t used its full water allocation since 1988, even though it has increased its irrigated area by 40 per cent since 1976. And who can argue with conserving water?

But we should be honest about why our government is willing to spend so much public money on irrigation upgrades. At the same time Kenney talks up efficiency, he’s been trying to rewrite water-use rules for the benefit of new coal developments and other industrial users, proposing to almost double the amount of water that can be pulled from the Oldman watershed. The bottom line is that more water than ever will come out of southern Alberta’s rivers, with the UCP government, in its own words, aiming to “allow market forces to drive water use, activity and innovation in the area.”

In short: A desire for more industrial activity, rather than an environmental ethic, is driving this expansion. But no industry can grow forever. Eventually, nature stops you.

Hiking in the sandstone canyons of southern Utah, Lorne Fitch thought he had solved one of the ancient world’s great mysteries. He and his wife, Cheryl Bradley, a retired botanist, were walking among Anasazi ruins that were abandoned 700 years ago. Fitch is a retired fish and wildlife biologist who spent 35 years in research as well as habitat protection. So as he and Bradley wandered the mesas and buttes, he thought about water. Drought is a common explanation for why the Puebloans fled the Four Corners. He had a eureka moment: “If only they’d had the presence of mind to get the federal government to subsidize irrigation!”

Fitch has lots of quips like this, rarely missing a chance to break tension with a joke. But his point is serious: Using more natural resources is rarely the solution to fundamental environmental challenges. Fitch and Bradley are both known for their water advocacy. Bradley represented environmental interests in the South Saskatchewan River Basin water management plan, and she volunteers for the Oldman Watershed Council and the Southern Alberta Group for the Environment. Fitch was involved with the Alberta Riparian Habitat Management Society and the Alberta Wilderness Association and has sat on conservation boards. They’ve found themselves taking unpopular positions on irrigation proposals. “Here we have a public resource, water, that has essentially been given to a farmer-owned co-operative to make decisions that no one else gets to make,” Fitch explains. “What are the public benefits of the massive infrastructure investment, which the public purse underwrites, to essentially grow crops for an export market?”

Proponents are quick to tout irrigation’s environmental benefits. It “conserves water” and “creates wetlands,” they argue, adding that industry has made great strides in efficiency. The Western Irrigation District, for example, has irrigated 20 per cent more land in the last two decades using 20 per cent less water. Michele Konschuh, an irrigated-crop scientist at the University of Lethbridge, says that “between 1999 and 2012 about 75 per cent of the water savings have been achieved by producers irrigating differently than they used to, going from things like gravity irrigation and high-pressure pivots to low-pressure pivots and subsurface drips.”

Yet expanding irrigation poses long-term risks to the environment. Average flows have been declining in southern Alberta’s rivers since 1971, and drought threatens in any given year. Removing too much water can harm wildlife, especially Alberta’s native fish species, many of which are already at risk. The entire South Saskatchewan basin (which includes the Oldman, Bow and South Saskatchewan rivers) was closed to new allocations in 2006 precisely because researchers discovered these impacts. But according to conservationists, the basin is already overallocated. Add climate change, which threatens to further diminish flows, and the stakes only get higher.

“Healthy ecosystems translate to healthy communities,” says Nissa Petterson, a conservation specialist with the Alberta Wilderness Association. “If we’re not meeting in-stream flow needs for having healthy trout populations, or healthy benthic invertebrate populations, all that has a trickle-down effect, and we’re going to be at the very bottom of it.”

People like Fitch, Bradley and Petterson are also concerned that, despite these risks, the irrigation expansion is being presented as a fait accompli. Yet some of the eight participating irrigation districts are still working out where the new reservoirs will go, and the plebiscites necessary for their construction haven’t happened. No consultation with environmental or Indigenous interests was conducted before the expansion was announced. The only entry point for environmental interests, it seems, is once the decision has already been made.

Southern Alberta has an almost inconceivable thirst. The region’s 13 irrigation districts represent Alberta’s single largest water user—between 60 and 65 per cent of all water used annually in the province. Strict regulations limit water use, and there is a history of districts going beyond even these. In 2000, with Alberta and Saskatchewan going through a drought, irrigation districts voluntarily cut their use by nearly a third.

Still, the districts’ licences entitle them to their water. In drought years, Albertans have relied on the districts’ goodwill. This was already a concern—and now irrigation districts must repay a huge loan, with water sales their chief source of revenue. None of this bodes well for balancing the rivers’ needs with farmers’. As Bradley says, “It makes sense to improve efficiencies, but what are you going to do with the saved water? It’s not allocated for the river.” Bradley sat on the conservation efficiency and productivity committee for the irrigation industry as part of an Alberta Water Council program. “I talked until I was blue in the face about how we’re putting huge amounts of public expenditures into these improvements and we know our rivers are stressed and degrading. Why don’t we agree to reallocate some of this water to the river?”

All of us bear the costs of a degraded environment and water scarcity. As irrigation districts represent fewer and bigger farms, and as multinational corporations increasingly depend on water for profits, it’s not hard to imagine a future where their interests clash with municipalities’ and wildlife’s needs, and where the districts aren’t as magnanimous as they were 21 years ago. Jason Unger, executive director of the Environmental Law Centre, asks, “If specific tributaries are low, then what are our management responses when, by intensifying use, we’ve created the expectation that the water will be available? [Economic] expectations typically trump any kind of environmental concerns.”

Sherm Ewing, in a 1991 book called The Range, interviewed dozens of Westerners about managing rangeland—ranchers, soil specialists, old-timers and everyone in between. One character, Allan Savory, came from Zimbabwe, where he’d earned a reputation as a “prophet” of resource management. He was shocked to see soil conditions in the plains worse than back home. The problem, he said, was that farmers treated resource management as crisis management, responding only when it’s too late. His prescription was proactive management: Before making decisions, “we test the air, like old-time miners carrying canaries,” he wrote. “When a bird drops off the perch, get the hell out of the mine.”

Ross McKenzie agrees. He is a retired soil and crop specialist who worked for Alberta Agriculture and Forestry in Lethbridge for almost 40 years and taught the only irrigation course at the University of Lethbridge. “I got to see some of the best and brightest,” he says. “A lot of [my students] moved into permanent positions with Alberta Agriculture.” He knows irrigation expansions require monitoring, research and expertise. In other words, proactive management.

That’s why this new irrigation expansion worries McKenzie. As governments are making an “historic” investment in irrigation, his former employer—the public body responsible for implementing these upgrades and monitoring their environmental impact—is being gutted. In the February 2020 budget, the UCP government announced nearly 300 layoffs in the agriculture ministry, almost half the entire staff. These accounted for 40 per cent of all government layoffs that year. Some researchers were transferred to the University of Lethbridge, but virtually all their staff were terminated. The irrigation demo farm was transferred to Lethbridge College, its lead researcher sent to the U of L. McKenzie’s bright students were all laid off. These cuts left the agriculture community dumbfounded. “We all knew when we voted Kenney in that there’d be cuts coming,” one anonymous source told the Western Producer. “But nobody thought they’d be so viciously targeted to the industry that’s carrying this province.”

The UCP cuts will reduce monitoring of this irrigation expansion and the long-term impacts of irrigation more broadly. “There was a group of people in Lethbridge who monitored water quality—the quality of water going into the irrigation districts and the water leaving them in runoff,” McKenzie explains. “They were doing a really good job helping the districts understand where problems are and where things can be improved. But every one of those people was cut in the last round of layoffs. So we’re putting more money into irrigation, but in terms of monitoring what we dump back into the Oldman River and the Bow River, and the water we pass on to Saskatchewan, who knows what’s going to be in that?”

Why would Alberta’s government gut its agriculture department? The consensus among many in industry is that Agriculture Minister Devin Dreeshen was appointed to dismantle his own department. Dreeshen is young, has virtually no work experience outside of conservative politics and is one of the most unabashedly far-right politicians in the province. (In 2016 he travelled through 28 states campaigning for Donald Trump.) He calls himself a farmer but comes from a wealthy, entrenched political background—his father, Earl, is a Conservative Member of Parliament, and Devin worked for former agriculture minister Gerry Ritz.

Dreeshen, however, is merely an avatar of agribusiness, of prioritizing corporate profits over workers and communities. Cargill, a multi-billion-dollar US-owned company, owns the largest meatpacking facility in Canada, located in High River. When it had North America’s single largest COVID-19 outbreak—almost half the workforce tested positive—Dreeshen lashed out at critics and refused to shut the slaughterhouse down. Two employees died from the virus. The RCMP are now investigating Cargill for criminal negligence. Dreeshen was also responsible for ending the Canadian Wheat Board even though a majority of farmers had voted to keep it.

More than that, while gutting his own department, Dreeshen formed Results Driven Agricultural Research (RDAR), an arms-length non-profit that funnels public money toward research projects generating private-sector profits. According to the Western Producer, RDAR “suggests that producer-elected boards will do a better job than publicly elected politicians and career agricultural researchers and scientific administrators in choosing priorities and direction for taxpayer dollars.” But almost half of RDAR’s board members aren’t even farmers, and if cost-cutting is the goal, it’s already failed. Savings from the agriculture and forestry cuts amount to $22-million, but Dreeshen has directed $37-million of public money annually toward RDAR.

When the objective is higher agribusiness profits and GDP, not the sustainability of rural communities, and when the government’s goal is brokering deals with global capital, the very department responsible for oversight of irrigation has been captured by corporate forces. That Dreeshen is one of the biggest proponents of expanding irrigation should be cause for concern. With the benefits going to the wealthiest farms, with environmental concerns shut out entirely, and with proactive management (i.e., credible research and monitoring) gutted, a public outlay of nearly $1-billion on irrigation seems more than imprudent. By accelerating the forces of agribusiness, it poses an existential threat to what’s left of rural life in Alberta.

Loss is central to rural Alberta’s story. The loss that homesteaders felt when the picture-perfect farm life they’d seen advertised turned out to be cold and cruel. The loss of cattle grazing on the open range. The loss of grain elevators, schoolhouses and entire towns. Today, it continues with the loss of the family farm, as well as the loss of the natural environment due to climate change. Prairie grasslands are disappearing faster than the Great Barrier Reef and the Amazon rainforest. Environment and Climate Change Canada says this country is warming at double the global rate, which could render significant amounts of Prairies farmland unfarmable.

By underwriting irrigation, our public dollars accelerate an economic development process that consolidates land and profits; further jeopardizes an already damaged environment; reinforces farm workers’ precarity; and drives out small, independent farmers. As presently managed, irrigation neither serves the public nor justifies its vast expense.

Robbie Jeffrey grew up on a cattle ranch near Islay, just west of the Alberta–Saskatchewan boundary. He now lives in Edmonton.

____________________________________________