On a late sunny day in August 2014, Progressive Conservative leadership candidate Jim Prentice jumped off his campaign bus at the Napa AutoPro in Boyle. He posed for a photo with some of the town’s EMS staff. He entered the shop with local MLA and then-education minister Jeff Johnson. The aspiring premier made his way around the room, having his photo taken with most of the 20-odd people crowded into the store. Prentice stopped at a middle-aged man in green overalls and a ball cap.

“What kind of operation do you have?” Prentice asked the farmer. “Mixed or straight grain?” Not a bad question for a Calgary lawyer more comfortable in the towers of Bay Street than the shops of Boyle’s streets.

“Straight grain,” came the answer.

“So you must be having a good year, since prices are up,” said Prentice.

“Well, you know, that’s if we can get it off and get it to port,” said the grain producer.

After more small talk, the politician moved off into the crowd, chatting and posing for more photos with the mostly supportive gathering. I spoke to the farmer.

“So, what did you think?”

“He seemed like a nice guy.”

“Will you buy a membership and vote for him?”

“Oh, no.”

“Why are you here, then?”

“See that fellow over there? He owns this place. I’ve been a friend of his since we went to elementary school together. He asked me to come out and meet Prentice. So I did.”

“Well, what do you think of Jeff Johnson?”

“He’s a great MLA. He comes down to Boyle and understands our issues; not like the former MLA, who just stayed in Athabasca.”

“So, will you vote for Johnson in the next election?”

“Oh, no.”

“Why not?!”

“Because after 43 years, the party is broken and can’t be fixed.”

There it was, plain as the sunburn on the farmer’s arms. After 43 years in power, the elites that form Alberta’s PC party had lost their touch at governing. For the farmer from Boyle, it was just a matter of time before the dead dynasty was voted out. The challenge faced by Prentice and his PC party was to repair the apparently irreparable.

Prentice brought to this challenge his experience as a 20-year veteran of property rights law, a former federal Conservative cabinet minister and a senior CIBC banker. He won the PC leadership with 77 per cent of only 23,386 ballots cast—a fraction of the 144,289 ballots cast by PC members in 2006. On September 15, when he was sworn in as premier, he started talking about the “Prentice Conservatives” and the “Prentice government.” After winning four out of the four by-elections only 42 days later, including his own seat in Calgary-Foothills, there was no doubt it was the Prentice Conservatives. When 11 Wildrose MLAs, including leader Danielle Smith, crossed the floor to join the PCs—effectively eliminating opposition—there was no doubt it was the Prentice government.

Prentice had revived a political corpse.

On May 15, 2014, Prentice launched his campaign to lead the PC party (and by default become the province’s 16th premier) in the Edmonton offices of CKUA radio, a former provincial Crown corporation now privatized. He personified Ottawa. He was aloof, standing at a lectern behind teleprompters that displayed his speech. In a far corner was a sail banner with green-and-blue Prentice campaign colours, the background for a later media scrum. The room was filled with an assembled crowd: former PC activists, former MLAs, former ministerial assistants and hangers-on who had not been at party events for years. Standing before this apparatus of authority, delivering a halting, almost uncertain speech, Prentice seemed remote. He was one step off the pace of provincial politics. Even three years in a corporate haven was a long time to be away.

Prentice distanced himself from Alison Redford and branded the PCs in his own image.

Afterwards, in front of the banner, Prentice spoke to journalists, redelivering the key messages in his speech. A few hours later he gave the same speech at the Metropolitan Centre in downtown Calgary. The scrum had different journalists, but the message was identical: leadership in healthcare, education, skills training and the environment; commitment to “sound, conservative fiscal principles”; an end to entitlements; maximizing the value of Alberta’s natural resources; respecting property rights. This was a programmed, blue-suit, cuff-linked, white-shirt politician who lacked authenticity, who was far distant from the kind of folksy populism Alberta voters have supported in the past.

By the end of a summer of revelations about former premier Alison Redford’s unusual renovations to the Federal Building in Edmonton, questionable expense claims and partisan use of government aircraft, Prentice had given over 700 speeches about why he should be the next PC leader. His jacket was off, his sleeves were rolled up, and he was expressing as much outrage about the excesses of his predecessors as his audiences.

Prentice never stopped campaigning, even after winning the PC leadership. On a lovely fall evening at a late-September annual convention of the Alberta Urban Municipalities Association, he spent an hour circulating the packed terrace of Edmonton’s Shaw Conference Centre. He plunged into the crowd, chatting, sipping beer and having his picture taken with everyone he talked to. His years out of politics no longer showed.

Alberta Premier Jim Prentice and former Wildrose Leader Danielle Smith speak to media after a caucus meeting in Edmonton Alta., Wednesday, December 17, 2014. Prentice’s caucus met to discuss a bid by at least half the official Opposition to cross the floor.THE CANADIAN PRESS/Jason Franson

The premier had perceived that Alberta politics is more small-town than national capital. Ottawa is seized with federal and international policy issues. Federal politicians don’t interact on a personal level with voters. The relationship between Albertans and their provincial politicians is much different, with smaller ridings and more opportunities to meet.

Prentice’s strategy was to distance himself from Redford. He sought to rebrand the PCs in his own image. This wasn’t surprising given the dead weight Redford had attached to a party that critics from both left and right charged had been drifting for years, its only goal to retain power.

Provincial politicians meet a lot of new people, especially on campaigns. During the PC leadership race, Prentice heard endless ideas on how to solve the problems, big and small, facing Alberta. He acted on several of those issues before launching the four by-elections.

In mid-September he announced four “starter schools” for Calgary, a concept somewhere between modular classroom and new school construction, to address enrolment pressure and, conveniently, boost his party’s image. Some Albertans called the $31-million investment a “Band-aid” solution, given the province’s booming population, and questioned the announcement’s timing, so close to a by-election.

Prentice announced a review of rural healthcare, an idea that emerged after he had visited the town of Consort, which has a small hospital with five acute-care beds and 10 long-term-care beds. Rural citizens have expressed concern that Alberta Health Services is too centralized and doesn’t seek local input when making decisions. The group conducting the review includes Bonnie Sansregret, the chair of the Consort and District Medical Centre Society.

Prentice also promised to construct 1,500 additional long-term-care spaces and to spend $70-million on sprinkler systems for seniors homes. Many of Alberta’s 24,000 government owned and supported seniors units were built before sprinklers were made mandatory under fire-safety codes.

After the by-elections, Prentice suggested he would make more than just the easy decisions. “I think the skill set I bring to public life… I am a very collaborative person,” he said. “I believe in hearing people’s opinions, I believe in searching out opinions that are vastly different than my own. I actually enjoy sorting through different people’s opinions to arrive at what I think is the right course of action.”

2006: As federal Indian Affairs minister, a position he held for 19 months.

Prentice is harsh in his judgment of Redford and her cabinet, characterizing the former premier’s time in office “as one of the most disappointing periods in our province’s history.” Ironically, many of the people he named to his first cabinet were Redford-era cabinet ministers. Of his 19 ministers, only four did not serve under Redford. Prentice brushed this off, emphasizing the political experience of Stephen Mandel and Gordon Dirks, two unelected ministers. Nonetheless, he was determined that many of the former premier’s policies be reversed in order to regain Albertans’ trust.

Prentice’s first decision was to scrap the fleet of government aircraft, which had become politically toxic. A report by Alberta’s Auditor General found that Redford and her office had used the aircraft inappropriately, for personal purposes. The planes were more economical than chartering aircraft to get Alberta’s political leaders to rural and remote communities, so Prentice could either save public dollars and keep the convenience of on-demand travel to remote parts of Alberta, or he could begin to repair his party’s political reputation. Selling the fleet was a declaration that future government business would not be like government business in the past. Prentice announced he would sell the planes.

Next he reversed the decision to eliminate the slogan “Wild Rose Country” from provincial licence plates. Former premier Dave Hancock had announced the new design, but the idea stalled when the Wildrose opposition used social media to spin the plan as petty partisanship.

Prentice promised new accountability for his government through legislation, hoping to change public perception of the PCs. Redford had been involved in awarding the contract of a $10-billion government tobacco lawsuit to her former husband. Prentice pledged to strengthen conflict-of-interest guidelines for political staff. Evan Berger was made a senior adviser to Agriculture in 2012 only weeks after the PC MLA had lost his seat. Prentice promised to lengthen the cooling-off period for political staff and senior civil servants. A handful of Redford’s office staff were given hundreds of thousands of dollars after, in some cases, just months on the job. Prentice swore an end to “sweetheart” severance packages.

Prentice brought experience as a property rights lawyer, a federal Conservative cabinet minister and a senior banker.

He decreed a competitive bid process for all public contracts except in extreme circumstances, which would require a prequalified vendor list. This was a reaction to criticism about untendered flood contracts in 2013, including one awarded to public relations consulting firm Navigator Ltd. to get the government’s message out. Albertans asked why public servants couldn’t have done the work themselves. Navigator staff includes Prentice friends Randy Dawson and Jason Hatcher; neither had official titles during Prentice’s leadership campaign, but as personal friends—and as image consultants with a national reputation—both influenced its design.

The new premier killed the Public Sector Pension Plans Amendment Act, an unpopular bill that would have overhauled pension plans for more than 200,000 public workers. (This reversal and others may be short lived: a Prentice mandate letter instructs the new Finance Minister to “address the competitiveness of public sector pension plans.”)

In the end, Prentice said the most significant change he made was not about entitlements or airplanes or licence plates. At an Edmonton PC fundraiser during the by-elections, he said the most important reversal was the decision to keep Red Deer’s Michener Centre open. “Probably the thing I hear most about on the doorsteps is the Michener Centre,” he told the audience. “People were saying, ‘You guys are compassionate. You were listening. What was happening wasn’t fair, and we are prepared to think about voting for you because of your willingness to change something that was wrong and do the right thing.’”

Quick decision-making characterized Prentice’s early days. He appointed a transition team during the leadership race. On their advice, he hired retired University of Alberta dean of business and former Alberta Liberal Party MLA and finance critic Mike Percy as his chief of staff, an appointment that surprised many. He also hired Patricia Misutka, one-time chief of staff to former Edmonton mayor Stephen Mandel, as his principal secretary, a senior aide.

From September 15, the day Prentice appointed his cabinet and senior staff, announcements poured out of his government: A new team of appointments to help him work on market access issues in Western Canada, the US and Asia. A performance review of agencies, boards and commissions to look at governance, how directors are appointed, succession planning and risk management. More new schools, to address the province’s booming population. Opening up Calgary’s McDougall Centre, the government’s southern Alberta headquarters, to the public. More money for the twinning of Highway 63. A new helicopter pad in Fort McMurray. The renewal of the city charter process with Edmonton and Calgary. A rural business development plan.

Fast decisions, however, are not the same as good decisions. Take Prentice’s September 26 announcement of flood mitigation measures in and near Calgary, seen by some as blatant electioneering during the by-elections. The City of Calgary was also not entirely pleased. Mayor Naheed Nenshi, happy that Prentice made flood mitigation a priority and named additional appeal officers under the Disaster Recovery Program, nonetheless issued a statement saying he was surprised the province would announce projects without consulting the city. The mayor and the premier subsequently met to clarify matters, but had Prentice not rushed to announce, he might have avoided friction. It was a rare slip-up from a premier who had so far managed to keep most of his potential critics silent.

The PC party and the provincial government have been remade in Jim Prentice’s name. His face is now synonymous with the government. This was no accident.

Prentice has near constant access to the 24/7 media cycle. Before him, opposition critics commanded media space with the sins of the Redford Conservatives. Prentice effectively reframed the message. Defining Alberta’s government as the “Prentice government” gave the premier an advantage. The opposition parties and other critics worked hard to tar Prentice with the sins of the Redford administration. But it didn’t work. Prentice mirrored Albertans’ privately expressed anger in public discourse. He defined his administration as new by giving it a different name. Throughout the four months of his PC leadership campaign Prentice told party members he was as upset as all Albertans with what had happened under Redford’s watch, and he was there to fix it.

Prentice banished the black cloud plaguing the PC dynasty and won over not only the disenchanted but also the formerly opposed.

Another example of reframing is Prentice’s response to the drop in world oil prices. The premier defined it not as a problem affecting the government, but as one affecting all Albertans. He noted that every one-dollar drop in oil prices amounted to a $200-million decrease in revenue to Alberta’s treasury and warned of a need for fiscal “caution” and “discipline.” For years, right-wing and left-wing critics alike have assailed Alberta’s government for its dependence on volatile oil and gas revenues, arguing that it has no shortage of policy options—such as taxes and savings strategies—to manage the problem. Prentice turned insecure public finance into an inevitable reality that Albertans must endure.

Using media this way, Prentice appears accountable while proactively controlling interpretations. This is in marked contrast to the Redford era, where her administration was merely reactive. Her communications staff spent much of their time on social media responding to criticisms raised by opposition parties and other government critics.

Throughout the four weeks of the by-election campaigns, and afterwards, Prentice repeatedly claimed Alberta was “under new management.” Albertans seemed to believe him.

Prentice is primarily interested in one issue: market access for Alberta’s natural resources.

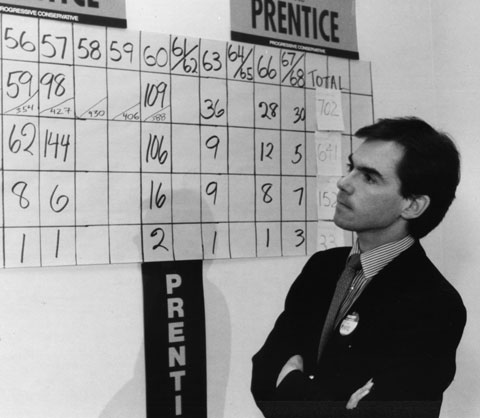

1986: A 29-year old Prentice running in the provincial election for the PCs in Calgary-Mountain View. He lost to the NDP.

That focus shows in his organization of cabinet. Of necessity he had to build most of his team from Redford’s cabinet, giving the most responsible jobs to those he most trusted: Finance (Robin Campbell), Energy (Frank Oberle), Municipal Affairs (Diana McQueen). He appointed outsiders to the largest departments: Health (Stephen Mandel) and Education (Gordon Dirks), and took Aboriginal Relations and International & Intergovernmental Relations for himself.

Gaining the co-operation of First Nations is key to his ambition to gain market access and diversify Alberta’s customer base. Prentice has a long history of working with Aboriginal communities (he is a former federal Indian & Northern Affairs minister) so it isn’t surprising he took this on. Many of the market challenges involve other provincial and territorial governments, so neither was it a surprise he took on Intergovernmental Relations. Taking these jobs allowed Prentice to reduce the size of cabinet, an early mandate nod to more efficient governing. But it invites the question of how well the premier can focus on these ministries’ other responsibilities—improving Aboriginal education outcomes, for example, or resolving interprovincial conflicts over scarce labour or commodities other than oil and gas.

On October 27, the night he was elected, Prentice spoke of only two challenges facing Alberta. “First, the eroding oil prices which have implications for our public finances,” he said. “Second, the challenge of market access that prevents us from achieving global prices for the important commodities that we produce in this province.”

To refocus Alberta’s international efforts on increasing sales around the world, Prentice replaced Redford’s appointments to Alberta’s offices in Ottawa and Washington, DC. He left the Ottawa office unstaffed. He appointed a former colleague, Rob Merrifield, who resigned as an MP to become Alberta’s senior representative to the US. He appointed a former diplomat, Ron Hoffman, as Alberta’s representative to the Asia Pacific Basin, replacing long-time PC MLA and one-time leadership candidate Gary Mar.

During a visit to Leduc during the PC leadership campaign, Conservative MP and former Prentice Ottawa colleague James Rajotte came to the Executive Royal Inn to lend his support. Rajotte spoke at the end of Prentice’s pitch and gave a number of reasons why he supported Prentice. One stuck out:

“I remember walking into his office in the Confederation Building [in Ottawa],” Rajotte said of their time as MPs. “I said, you know, your furniture is different from every other office; what’s going on here?”

“He said, ‘Well, I furnished it myself.’ I’m sure [Prentice’s wife] Karen had a big hand in that, but he said, ‘I just believe I should furnish my own office.’”

“I said, ‘That’s kind of taking public service to the nth degree, Jim.’ But that’s what he did each and every day in Ottawa. He took public service to the nth degree. He understands the meaning of that phrase and those terms.”

Prentice understands the importance of stories that appeal to voters. His challenge was to repair and rebrand a party that had been in power for more than four decades. From his September swearing-in to the December break, the premier did what few would have thought possible. He banished the black cloud plaguing the sclerotic PC dynasty and won over not only the disenchanted but also the formerly opposed.

Before the next provincial election, Prentice will have to raise millions of dollars for the PCs’ campaign, recruit talent to run for his party, and increase party membership, since numbers have fallen to a record low. He will also need to deal with the fallout from a 2015 budget that, given the low price of oil, will likely entail significant changes to both revenue and spending.

But Prentice sees politics as a test. “It is a test of endurance,” he said in a post-leadership campaign interview. “It is a test of ability. And it is sometimes, for sure, a test of patience. But above all else, it is a test of character. When you enter public life, you take only one thing with you. And that is your reputation and your integrity. And when you leave public life you take only one thing with you: your reputation and your integrity.”

Prentice’s challenges in the days ahead may be very difficult. But so far, against all odds, he has resurrected both his party and the PC government. He has proven the farmer from Boyle wrong.

Paul McLoughlin, publisher of Alberta Scan, has been covering Alberta politics since 1983, when Peter Lougheed was premier.