I hear children giggling, wood being chopped and wind blowing through towering lodgepole pines as I use the back of a hatchet to tap my tent stakes into the soft, pine-needle-covered earth. It’s a warm Friday in mid-August, and I’ll spend the evening around a campfire before tucking myself into a cozy sleeping bag under the stars and waking up to cook breakfast on a propane stove propped on a picnic table.

I’ve enjoyed camping since childhood and it continues to bring me great joy as an adult. Whether trekking for hours with a 40-pound pack into a backcountry site, backing my Boler trailer into a serviced campground, or dodging potholes and dirt bikes while searching for the perfect spot to pitch a tent and hang my hammock on Crown land, I love the entire experience.

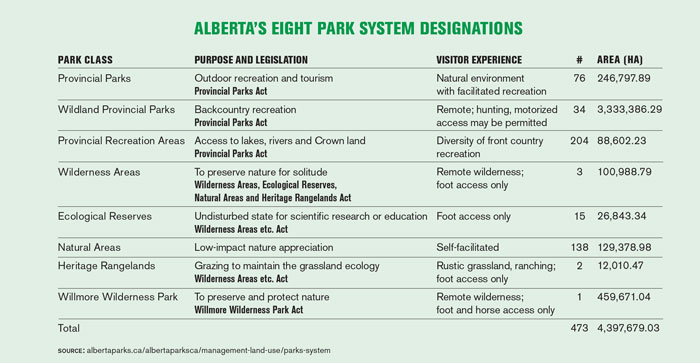

For those of us who like to camp, hike, picnic, climb, canoe, ski, hunt or fish, Alberta has vast areas of wilderness that make these activities possible. Our parks system is made up of 473 sites that range in size, amenities and style. They span nearly 4.4 million hectares in diverse landscapes from Rocky Mountains to desert badlands. And our parks are “an equalizer for our society,” says Natalie Odd, director of the Alberta Environmental Network. “You don’t have to be an adventurer with all the best equipment and, you know, lightest-weight whatever. You can just very easily get to a park and enjoy it for a day—that’s something all Albertans can share.”

But this system of day-use areas and overnight campgrounds—one that began in 1930 with just a single site at which to picnic and swim, thanks to a premier who argued for parks legislation—has been the target of cuts by Jason Kenney’s United Conservative Party government.

Changes to more than a third of the sites in Alberta’s parks system were announced via a news release on a Saturday in February 2020. The “optimization,” which was introduced with no public consultation and branded as a way to save $5-million by closing “small and under-utilized” sites, included ending cross-country ski tracksetting at three mountain locations, closing 10 parks and two visitor centres, partially closing a further 10 parks, and removing 164 sites from the parks system and making them available for “partnership opportunities” or “alternate management approaches” or “sale or transfer.” In the months that followed, a freedom of information request revealed that Environment and Parks Minister Jason Nixon had ignored advice from his staff to consult the public. Also, contrary to government claims, data showed the parks to be widely used.

Cataract Creek Provincial Recreation Area was on the UCP’s February 2020 list of sites slated for “removal.” Surrounded by forest, it has 102 campsites, each with its own picnic table and firepit, first-come, first-served.

Cataract Creek Provincial Recreation Area was on the UCP’s February 2020 list of sites slated for “removal.” Surrounded by forest, it has 102 campsites, each with its own picnic table and firepit, first-come, first-served.

Along with hundreds of thousands of other Albertans, I flocked to our parks in the summer and fall of 2020 as COVID-19 restrictions kept most of us adventuring closer to home. I visited nearly a dozen provincial recreation areas (PRAs) slated for closure and spent more time than ever exploring public land use zones (PLUZes) and backpacking in wildland provincial parks. I saw first-hand the many different types of parks and why this variety is a strength, given the wide range of parks users. I witnessed just how busy our “under-utilized” PRAs actually are, and I glimpsed what these sites could look like if they lose status.

I was upset when the parks changes were announced, and I spoke out on Twitter, radio and in a national newspaper op-ed. My summer and fall adventures only reinforced my belief that these spaces must keep their designations. We need them. Future generations need them. The existing parks system, which was stewarded by our government for 90 years and enjoyed by millions of citizens, wasn’t broken. So why was the UCP trying to “fix” it?

My travels included visits to postage-stamp-sized protected areas surrounded by seas of Crown land. These tiny PRAs are pockets of order amid sprawling lawlessness and we desperately need these enclaves of rules, these spaces that serve as an easy introduction to the great outdoors.

One campground I visited in mid-August is a 90-minute drive from Calgary, 45 kilometres southwest of Longview and 12 kilometres down a dusty forestry trunk road, in the Cataract Creek PRA. Surrounded by forest, it has 102 campsites, each with its own picnic table and firepit. These unserviced sites work on a first-come, first-served basis—you claim your spot, drop your payment in a locked box and can stay for up to 16 consecutive nights.

When my partner, dog and I arrived after work, around 6 p.m. on a Friday evening, about a dozen sites were vacant. Around the campground’s two loops were small mountaineering tents, massive RVs, vintage Vanguard motorhomes, well-loved tent trailers and even a gleaming, metallic Airstream. The next morning we awoke to find campers at the site across from us kneeling on mats laid across a blue tarp, praying in the direction of Mecca, some 11,000 kilometres away. Up the gravel road, early-rising kids shrieked as they raced scooters past a lineup of pajama-clad campers waiting at the outhouse. On any morning in June, July or August you’ll find such a scene at many Alberta parks and recreation areas.

At the water pump, I met Wameq Ameri as he filled a jug for his family. It was his first visit to Cataract Creek. Ameri explained that while he didn’t grow up camping, he’s overjoyed to be raising kids who love it: “When they hear we’re going camping, they’re excited.”

A handmade note in Kananaskis Country. With pincnic tables, firepits, road signs, bear-proof garbage cans, and outhouses, provincial recreation areas are tiny bastions of order surrounded by the chaos of Crown Land.

About 10 minutes up the road is another busy campground. The Etherington Creek PRA has 61 campsites, and, like Cataract Creek, is among the 164 places, most of them PRAs, which were slated to be removed from the parks system. When we drove through, a homemade sign with two hearts drawn in Sharpie and the words “Support Alberta Parks” greeted campers and urged them to write their MLAs to express opposition to the UCP cuts.

When the cuts were announced, reaction was fierce from outdoor groups, parks users and non-profit organizations devoted to preserving wildlife and natural spaces. “Nobody asked for this,” says avid parks user Phillip Turnbull. “The UCP didn’t campaign on jobs, economy, pipelines—and cutting parks.” He recalls feeling “so many emotions” when he heard about the changes last year. “But I guess outrage probably sums it up.”

At a virtual event about the parks cuts, Will Gadd, a prominent mountain athlete and public speaker, described how he grew up in Alberta, spending most of his spare time in parks and wild places. Today, as a guide, he shows them off to people from around the world. “The idea of getting rid of some of these… when I explain it to them, they’re like, ‘You’re kidding, right? No one could be that short-sighted,’” Gadd said. “And the answer is, unfortunately, yes [they could be].”

After the government announced its intentions, petitions launched, social media lit up and protests were scheduled for the legislature in Edmonton and at Calgary’s McDougall Centre, where attendees were encouraged to pitch a tent, make a sign on recyclable materials and dress in skiing, climbing or hiking gear. But Alberta’s first case of COVID-19 was identified in early March, and organizers were forced to cancel the gatherings. Over the ensuing months the virus changed how we lived, socialized and worked—and more Albertans than ever headed outside. Attendance at provincial parks boomed.

Our parks system is divided into eight classifications, including provincial parks, wildland parks (which are more remote), provincial recreation areas, wilderness areas, ecological reserves, natural areas, heritage rangelands and the distinct Willmore Wilderness Park. Each allows for different activities, visitor experiences and levels of landscape protection. Alberta is also home to 19 PLUZes, more commonly referred to as Crown land or public land. These vast areas have fewer restrictions than parks and provincial recreation areas and are considered the wild west of camping. They’ve also grown in popularity in recent years as GPS devices and social media have made them more accessible.

This improved access, along with a growing population, has meant “recreational pressures that produce undesirable impacts on land, vegetation, water and wildlife, as well as increase conflicts between public land users,” the government acknowledges. I saw a whole range of such pressures last summer, from graffiti on crumbling bridge abutments to bullet holes in signs, massive ruts in gravel roads eroded by trucks and the knobby tires of off-highway vehicles, garbage strewn here and there, omnipresent beer cans and the occasional pile of human feces topped with sun-weathered toilet paper flapping in the breeze.

PRAs, at least, have a long list of rules. Pets must be on leash; quiet hours must be respected; the consumption of alcohol is limited; the number of vehicles allowed at a site is capped; the use of off-highway vehicles is restricted; campfires must be kept to designated fire rings only. But these mainstays at defined campgrounds are virtually non-existent on Crown land.

Livingstone PLUZ, just a 15-minute drive from Cataract Creek PRA, might as well be a world away. The relative order of numbered sites, picnic tables, firepits and outhouses quickly gives way to RVs and trucks that dot every flat part of the landscape. While regulations vary depending on the PLUZ, you can typically camp wherever you like on public land, as long as it’s at least 30 metres from a lake or stream.

The sounds and smells are different too. On Crown land, quads rev, guns fire and music blares. With no outhouses or garbage facilities, campers are encouraged to dig a small hole in the earth, do their business, then fill the hole back up with soil and pack out their toilet paper. But as anyone who has camped on Crown land can attest, this rule is rarely followed to the letter. A friend spent one evening this summer shovelling human feces away from what he thought, at first, was the perfect campsite at a popular location in the Upper Clearwater/Ram PLUZ. While staying at the Ghost PLUZ in September, I found an old patio chair, with a hole cut out from its seat, placed in the river. A roll of toilet paper was stashed nearby.

According to a 2015 study by the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society (CPAWS), 77 per cent of Alberta campers prefer designated sites over random camping, because of the amenities, services, access and convenience. But those who like random camping really like it. They rave about the freedom, the open skies, the lack of rules, the fact you don’t have to book in advance and you’re not sandwiched next to your neighbour. There’s a perceived political divide between these groups, with conservatives favouring personal freedom—including the freedom to set up camp wherever you like, drive ATVs and shoot guns.

I’m one of those rare Albertans who enjoy designated sites and Crown land. I like the thrill of going off the beaten track and hunting for the perfect spot, and the freedom that comes with a lack of rules. While I resent what some random campers do to the environment and prefer the symphony of nature to the drone of dirt bikes, I’ve also been to designated sites where neighbours have blasted music and thrown beer cans into the bushes. One of my favourite camping trips occurred a few Canada Day long weekends ago when 15 friends and I descended on Crown land in BC, which we had entirely to ourselves. The late-night singalongs, dogs chasing each other off-leash, and sheer size of our roaring campfire wouldn’t have been possible at a designated campground, with other

campers nearby.

Last summer, at the Livingstone PLUZ, my partner and I parked on an old logging road ravaged by off-highway vehicles and hiked up Mount Livingstone, the region’s namesake peak. We had the entire mountain to ourselves—a common benefit of adventuring on public land—and marvelled at the 360-degree views from the summit. Back at our car, we drove down Highway 40, south of Cataract Creek, and explored four more recreation areas on the government’s list for “partnership,” each adjacent to public land, where fifth-wheels of all shapes and sizes sat under a big blue sky. With their picnic tables, firepits, road signs, bear-proof garbage cans, and outhouses, these PRAs are tiny bastions of order surrounded by the relative chaos of Crown land. The PRAs Livingstone Falls, Oldman River North, Dutch Creek and Racehorse Creek have a total of 115 designated campsites. After driving through all of these, we counted a grand total of five vacant campsites. So much for being “underutilized.”

The sounds and smells are different on Crown land. Quads rev, guns fire and music blares. While staying at the Ghost PLUZ, I found a patio chair, with a hole cut out from its seat, placed in the river.

On this particular evening we were drawn to the freedom of the hills and intended to pitch our tent on Crown land. So we kept driving, and as the gravel road twisted and turned, we were impressed by the creativity campers had employed to guide friends and family to the spaces they’d claimed. In an area with no cellphone reception, all manner of makeshift signposts scrawled on paper plates and beer boxes were staked into the ground or affixed to trees. “Wait,” I said, as my partner slammed on the brakes to verify what we thought we saw.. “Is that… a bouncy castle?”

We reversed and discovered our eyes hadn’t deceived us. There was indeed a large, inflatable children’s play place standing tall in the middle of nowhere. Next to it was an off-highway vehicle, two small children on a dirt bike, and two long camper-trailers—a striking image of camping on Crown land.

As we kept driving, scanning for a place to set up a more modest camp of our own, we passed a Yield sign peppered with bullet holes, dodged oncoming dirt bikes, and watched as a herd of cows was guided away from the road by a team on horseback. I wondered if, under the UCP’s plan, the enclaves of designated campgrounds we’d visited earlier would be absorbed into this free-for-all.

“It’s clear there’s a huge difference between parks and public land; both are important to the lives of Albertans,” Becky Best-Bertwistle with CPAWS said at a virtual information session in November. “[But] removing parks from the system will be almost impossible to reverse, and after the year we’ve had, Albertans want more parks and protected areas.”

Diversity is a key feature of Alberta’s parks system. Random camping is intimidating for tourists, for people new to camping, even for many Albertans who go a couple of times a year. Not everyone has the high-clearance truck or SUV needed to navigate the rough roads on a lot of public land. Not everyone is comfortable without cell service. And, let’s be honest, not everyone is OK with digging a hole to poop in. Conversely, not everyone loves the limitations of a designated campground, the proximity to neighbouring campers, or all those rules. There’s something freeing about staking out a piece of raw territory as your own, if only for a weekend.

Alberta’s parks system is strong because it offers this range of options. It has fully furnished yurts and flush toilets for people new to camping, well-marked trails near major centres for novice hikers, and visitor centres where people can ask staff for tips and advice. People new to hiking or fishing can get their feet wet by bringing rented equipment to an amenity-rich facility a quick drive from a city, while those who’ve been heading outside for decades and own vehicles, trailers and toys specific to their hobbies have swaths of remote land to explore.

Clockwise from top: A sign peppered with bullet holes. In an area with no cellphone reception, makeshift directions are scrawled on paper plates. Some trails allow all-terrain vehicles, quads and dirt bikes.

While Albertans spent the pandemic summer and autumn outside, questions and confusion swirled about the future of the places they were exploring. The opposition NDP launched a “Don’t Go Breaking My Parks” information and sticker campaign in July. In August the Alberta Environmental Network and the Alberta chapters of CPAWS unveiled a “Defend Alberta Parks” lawn-sign initiative. Natalie Odd, with the AEN, was thrilled when the first 20 signs went out the door in August. “I thought these signs might last us for months,” she recalls of the initial 1,000 orders. “It didn’t turn out that way.”

The campaign, which launched on a shoestring budget, had by the end of 2020 seen some 1,500 volunteers deliver more than 17,000 signs to addresses across the province. Odd believes this success owes to the simple message and Albertans’ deep connection to their wild spaces. “This is about our personal experience in the outdoors with our families,” she says. “It’s a very important part of our experience living in Alberta.”

Other campaigns similarly united parks users. “I didn’t want to just sit around and complain. I wanted to actively do something to try and make a difference,” says Phillip Turnbull, who created and sold a 2021 calendar featuring photos of Alberta’s parks, with profits going to organizations fighting the cuts. Geospatial scientist Tanya Yeomans mapped the affected locations and collected stories about each park from people who’d visited them. “The same spot may be a place to grieve the loss of a family member and also a place to propose to a loved one,” she wrote about her project. Sparked by “a buildup of frustration and creative energy,” Nakita Rubuliak coordinated Arts for Alberta Parks (see p 62), which saw artists create a piece inspired by each park on the list for removal. In response to UCP claims that sites on the chopping block were underutilized, a project called “I Use Alberta Parks” asked people to share personal stories about the sites they visited.

Premier Jason Kenney repeatedly downplayed his government’s changes and characterized opposition to the cuts as “foreign interest groups like green left organizations that are lying to people in order to raise money.” But critics dismissed this as rhetoric. NDP opposition leader Rachel Notley said at a July 2020 press conference, “The premier is being too cute by half when he says no parks will be sold. That’s true. But what they’re doing is reclassifying provincial recreation areas back into public lands, which then can be… sold off or leased to other private groups. And this opens up these areas to private commercial use.”

In November 2020 the UCP unveiled a “My Parks Will Go On” campaign to counter what they called “misinformation.” Environment Minister Nixon also hosted a virtual parks town hall, which marked the first opportunity Albertans had to ask him about the changes—nine months after they’d been announced. Moderators, however, disabled the chat function through which the public could ask questions, with most of the live questions instead coming from Nixon’s UCP colleagues. Nixon told viewers “the reality is we actually have not changed anything really significantly within our system.” The Defend Alberta Parks campaign continued to receive sign requests.

And then, in late December 2020, the government posted yet another press release. “As part of Budget 2020, Alberta’s government decided to work with Albertans to continue operating a number of provincial parks facilities across the province,” it announced—as though the proposed park closures, and the justification of saving government some $5-million, had been a figment of the public’s imagination.

From the start, government communication on this file has been secretive, deceptive and confusing. The UCP’s backtracking press release landed in reporters’ inboxes after 4:00 p.m. three days before Christmas. It said, “All sites will maintain their parks designations,” and declared the government had “secured or maintained partnerships for 170 parks and public recreation area sites.” In followup interviews, Nixon refused to name the partners, say how many were new or divulge what activities would be allowed under the partnerships.

Skeptics of a government that refuses to answer questions and shifts its messaging simply don’t believe the plan has been walked back. They worry that parks and campgrounds could still lose protection through legislative changes as part of the Kenney government’s parallel revisions to public land management, a process which remains ongoing. Many areas on the “partnership list” are surrounded by coal leases, with coal exploration having ramped up under the UCP—new leases sold, new roads built and exploratory holes drilled. And then there’s the issue of who the partners are and what they’ll be allowed to do.

I too remain unconvinced. I wonder if protected sites will be absorbed into adjacent Crown land, or if they’ll be sullied by coal mining, or if new private “partners” will transform them into RV parks, chopping down trees in an attempt to squeeze in as many sites as possible and maximize profits.

As I read the December news release, I couldn’t help but think about my adventures last summer. The evening after we stayed at Cataract Creek PRA, my partner and I found a spot to random camp in the Livingstone PLUZ. As our dog raced around and gunshots rang out in the distance, we found a flat patch of relatively brush-free land amid the dried cow dung, rock-ring firepits and cans and garbage that had been left behind, to stake our tent and hang our hammock.

This isn’t the future our protected parks and PRAs deserve. I’d hazard to guess it’s not what Alberta’s fifth premier, John Brownlee, had in mind when he created our parks system in the late 1920s. I’d bet, too, it’s not what Premier Peter Lougheed imagined when he worked tirelessly in the 1970s to protect large swaths of land in the Rockies. Alberta’s parks system truly has something for everyone, no matter if you’re new to the great outdoors or, like me, you’ve been enjoying it for decades. These spaces exist thanks to a long line of politicians who came before Kenney, leaders who had the foresight to think about future generations.

Annalise Klingbeil is a former Calgary Herald journalist. She co-writes GoOutside.substack.com, a weekly newsletter about the great outdoors.