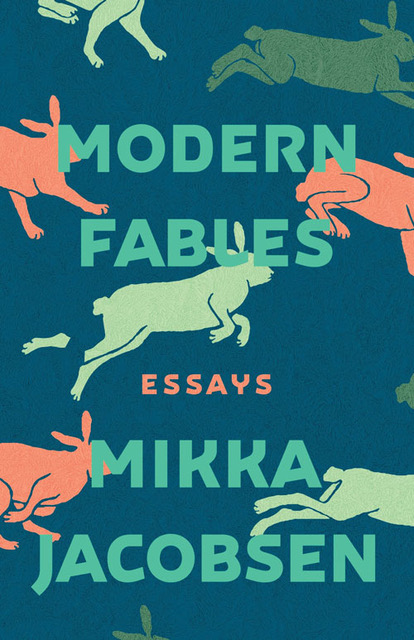

Modern Fables is the impressive first collection of essays from Calgary writer Mikka Jacobsen. At their most capacious, these essays are several things at once: character portraits, emotional reckonings, cultural and literary analysis and glimpses of history. The “fables” part is surely a subversion, pointing to the book’s mockery of conventional moral standards, but even so: if succinct morals are now impossible, Jacobsen implies that moral ponderings—How should we live? How behave in this particular time?—remain necessary and unavoidable.

The essays articulate a particularly Albertan personal history. They are about growing up, into near-middle age, about dating and loving and being a woman with a thinking, reading life. In “Parlour Tricks,” Jacobsen draws a line between an Albertan maleness and conservative politics: “I now wonder if Harper’s brand of cowboy government doesn’t reflect a particularly Calgarian ethos reminiscent of the drug-slinging boys of my youth.” “The Wake” is partly a grim coming-of-age narrative, centred on the funeral of an old friend, which has “the air of a high school reunion…. We are still so thrumming with life that death seems a feverish occasion… like a bush party or a prom.”

But the whole collection is not grim at all. In the hilarious “Kurt Vonnegut Lives on Tinder,” the narrator observes that “Nearly every second male profile lists Kurt Vonnegut as its favourite writer.” From there, she reports on the results of her “timely and novel literary experiment” to date only self-professed Vonnegut lovers. The superb “Me vs. Brené Brown” traces the narrator’s brief infatuation with Brown’s famous TED talks on empathy and shame and moves to a nuanced evaluation of both Brown’s brand and shame itself. And if a funeral makes for dramatic emotional reckonings, weddings do too. “Like characters in fiction, there are two kinds of weddings,” Jacobsen writes in “The Wedding Plot,” “impressive and flat.”

Jacobsen’s voice is sharp, self-deprecating and funny, and her fierce intelligence muscles through the whole. It’s clear from the sentence cadences and the attention to structure that this writer understands the importance of style, and hers seems particularly of the now: versed in literature and philosophy as much as texting lingo (“This book is amazee!” she texts an academic friend, who in turn texts an avatar of himself leaning on a donkey), vulnerable and self-revealing yet cuttingly critical. Although more cerebral, the ethos here is reminiscent of Sheila Heti—unafraid to reveal its own intellect as it pushes through doubts, romanticisms and conventional delusions, toward revelation and a shimmering, precarious clarity.

Jasmina Odor is the author of You Can’t Stay Here.

_______________________________________